Evaluation of the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program

Title: Evaluation of the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program

Organization: Parks Canada Agency

Date: February, 2023

List of tables and figures

List of Tables

| Number | Titles |

|---|---|

| Table 1 | Acronyms and abbreviations |

| Table 2 | Ecological integrity monitoring definitions |

| Table 3 | Number of indicators monitored by park (2020) |

| Table 4 | Review of available State of the Park Reports |

| Table 5 | Financial data for the EIM Program, 2015-16 to 2019-20 |

List of Figures

| Number | Titles |

|---|---|

| Figure 1 | Logic model (Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate) |

| Figure 2 | Logic model (Operations) |

| Figure 3 | Percentage of survey respondents who felt that EI measures enable an accurate summary of chosen EI indicators |

| Figure 4 | Percentage of survey respondents who felt that EI indicators represent essential ecosystems |

| Figure 5 | Percentage of survey respondents who felt that the ratings assigned to EI indicators accurately reflect the state of the ecosystems |

| Figure 6 | The EIM Program's contributions towards national and international targets |

| Figure 7 | Flow of EIM decision-making |

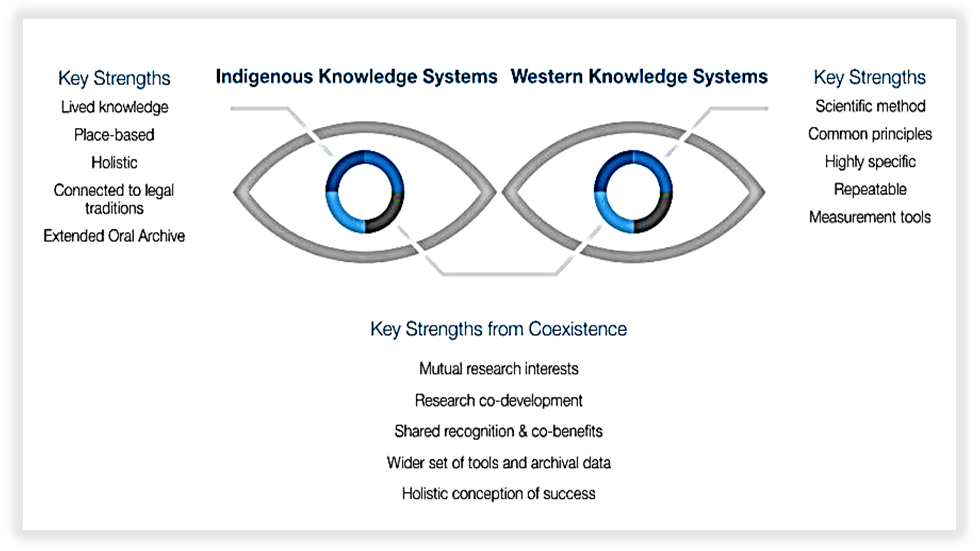

| Figure 8 | Two-eyed seeing approach |

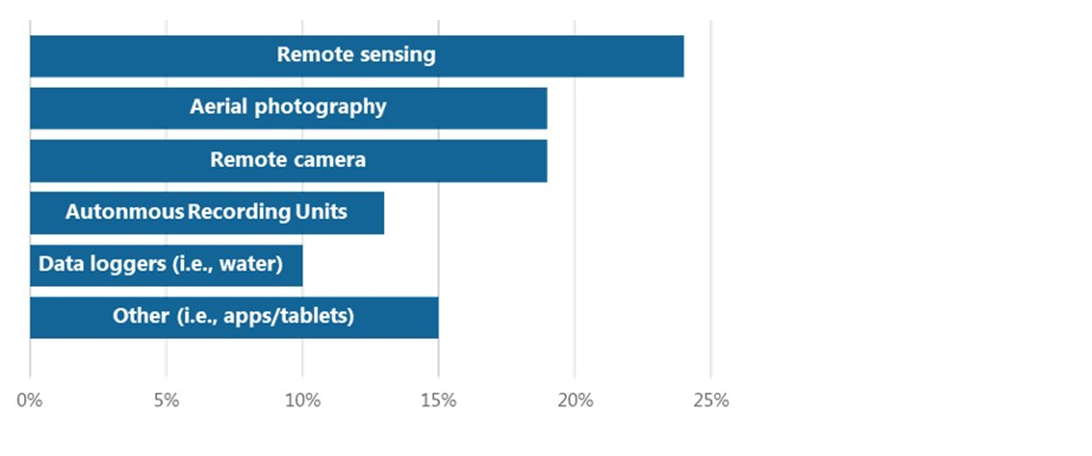

| Figure 9 | Types of technology used to aid EIM data collection |

Acronyms and abbreviations

| Acronym | Full name |

|---|---|

| BIA | Basic Impact Assessment |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CESI | Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators |

| CIM | Conservation Information Management |

| CoRe | Conservation and Restoration |

| DFO | Fisheries and Oceans Canada |

| DIA | Detailed Impact Assessment |

| DPR | Departmental Performance Report |

| DSDS | Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy |

| ECCC | Environment and Climate Change Canada |

| EI | Ecological Integrity |

| EIM | Ecological Integrity Monitoring |

| EMD | Ecological Monitoring Division |

| FSDS | Federal Sustainable Development Strategy |

| FUS | Field Unit Superintendent |

| GoC | Government of Canada |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| IA | Impact Assessment |

| ICE | Information Centre on Ecosystems |

| IWG | Independent Working Group |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| NRCan | Natural Resources Canada |

| PAD | Peace Athabasca Delta |

| PAEC | Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation |

| PMP | Park Management Plan |

| RCM | Resource Conservation Manager |

| SAR | Species at Risk |

| SARA | Species at Risk Act |

| SEA | Strategic Environmental Assessment |

| SOPR | State of the Park Report |

| TBS | Treasury Board Secretariat |

Introduction

Ecological integrity monitoring

Ecological integrity

In the Canada National Parks Act (2001), section 2(1), Ecological integrity (EI) is defined as:

"…a condition that is determined to be characteristic of its natural region and likely to persist, including abiotic components and the composition and abundance of native species and biological communities, rates of change, and supporting processes."

Ecological integrity monitoring

Ecological integrity monitoring (EIM) is a park management tool that supports conservation objectives through the development and monitoring of EI indicators and measures. The data collected is used to communicate the conditions of park ecosystems and to measure progress in attaining management objectives. Parks Canada is committed to improving EI in targeted parks.

The Canada National Parks Act (2001) defines the importance of EI for Parks Canada:

"Maintenance or restoration of ecological integrity, through the protection of natural resources and natural processes, shall be the first priority of the Minister when considering all aspects of the management of parks" (Section 8.2).

The 2011 EIM Guidelines describe the EIM Program as providing medium and long-term data for assessing and reporting overall park EI. It is summarized in a small suite of approved EI indicators and supporting measures that are carefully selected to represent the biodiversity and biophysical processes of park ecosystems in the context of the larger scale natural processes.

Definitions

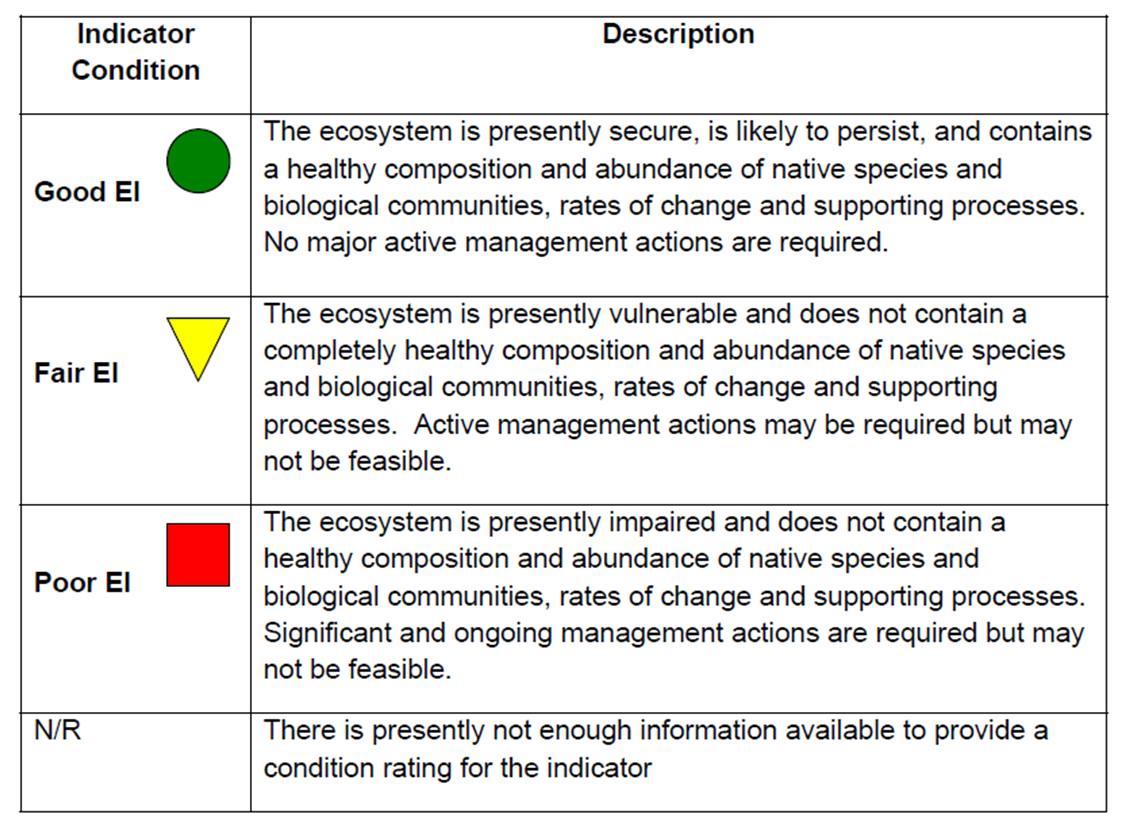

Baseline data are the base used for measures and are crucial to establishing meaningful thresholds. The determination of thresholds is the science-based point at which the ecosystem condition changes (e.g., from fair to poor). The rating for each threshold is rolled up to produce a condition rating for each indicator within a park.

A trend is then determined based on the change in the condition rating.

See Annex 3: Indicator Condition Ratings, for further description of the good, fair and poor ratings.

| Definition | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Measure | Each indicator is a composite index of measures selected to track the key biodiversity and ecological processes within major park ecosystems. | Water quality, moose density, soil decomposition, etc. |

| Threshold | Level of an indicator or measure that represents the science-based point at which the condition changes. | From poor to fair, fair to good, or fair to poor, etc. |

| Indicator | Represents major park ecosystems that occur in a park and are chosen from the national suite of indicators. Parks choose between three to four indicators. It is recommended that each indicator is assessed by five measures. | Forest, tundra, scrublands, wetlands, grasslands, freshwater, coastal/marine and glaciers |

| Condition | The current assessment of the level of EI of an indicator based on defined thresholds for measures and indicators. | Good, fair, poor, undetermined |

| Trend | A specific measurable change over time of the EI of a measure or an indicator. | Improving, stable, declining, not rated |

Program overview

Foundational documents

- 1994: Parks Canada Guiding Principles and Operational Policies (ecological integrity features prominently)

- 2005: Monitoring and Reporting Ecological Integrity in Canada's National Parks: Volume 1, Guiding Principles Evaluation questions

- 2007: Monitoring and Reporting Ecological Integrity in Canada's National Parks: Volume 2, A Park-Level Guide to Establishing EI Monitoring

- 2010: Ecological Integrity Monitoring in Northern National Parks – Pathway to 2014

- 2011: Consolidated Guidelines for Ecological Integrity Monitoring in Canada's National Parks, Parks Canada (replaces two previous guides)

- In development: Standards on Ecological Integrity Monitoring

Program overview

The EIM Program is a long-standing program within Parks Canada that gathers longitudinal EI data to help inform decision-making. Ecological integrity was highlighted within the 1994 Parks Canada Guiding Principles. Since then, there have been several key foundational documents developed (see above), further defining the details of data collection and assessment.

The EIM Program currently follows the Consolidated Guidelines for Ecological Integrity Monitoring in Canada's National Parks (2011). These Guidelines outline key EI concepts and provide management with direction to support field unit superintendents (FUS) in maintaining or improving EI in national parks.

Program governance

At Parks Canada, the Ecological Monitoring Division (EMD) leads the efforts within the Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation (PAEC) Directorate in providing functional direction for Parks Canada's EIM Program.

Within field units, field unit superintendents are responsible for implementing the 2011 EIM Guidelines. This includes selecting measures, thresholds and indicators (see Table 2: Ecological Integrity Monitoring Definitions). Field unit staff, led by resource conservation managers (RCM), conduct on-the ground data collection.

Further details on the role of staff within PAEC and field units can be found in Figure 1: Logic model (Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate) and Figure 2: Logic model (Operations).

Logic model

| Ecological Monitoring Divison (EMD) | Conservation Information Management (CIM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Activities |

|

|

| Outputs |

|

|

| Direct Outcomes |

|

|

| Intermediate Outcomes |

|

|

| Field Units | |

|---|---|

| Activities |

|

| Outputs |

|

| Direct Outcomes |

|

| Intermediate Outcomes |

|

About the evaluation

Evaluation questions

- To what extent is the program aligned with Government of Canada (GC) and Parks Canada priorities that address a societal/environmental need? (Relevance)

- How relevant are the chosen ecological indicators and measures? (Relevance)

- How consistent is the program with relevant international norms and standards on ecological integrity? (Coherence)

- To what extent is the program achieving its direct outcomes? (Effectiveness)

- To what extent is the program achieving its intermediate outcomes? (Effectiveness)

- To what extent does the current model for the delivery of the program result in the efficient delivery of activities? (Efficiency)

Treasury Board Secretariat – Policy on Results (2016)

The evaluation of the program is consistent with the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Policy on Results (2016), which requires periodic evaluation coverage of all departmental programs and spending.

Consistent with the requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016) and associated Directive on Results and Standards on Evaluation, this evaluation examines the relevance, coherence, effectiveness and efficiency of the EIM Program for the period between 2015-16 and 2019-20.

Scope

The scope is limited to EI condition monitoring within national parks. Effectiveness monitoring in national parks, ecosystem monitoring activities in national marine conservation areas and ecosystem monitoring activities in the national urban parks are excluded from the scope of this evaluation.

The Information Centre of Ecosystems (ICE) web application was explored as it related to the EIM Program but was not a focus of the evaluation.

Lastly, the evaluation did not explore the details related to the scientific rigour of EI measures, thresholds, indicators or condition ratings, or the accuracy of data input at the field unit level. The evaluation did however, assess the relevance of EI measures and indicators in monitoring and representing park ecosystems.

Lines of evidence

Data from multiple lines of evidence were collected for the evaluation. These included:

- Document and file review;

- Literature review;

- Survey;

- Case studies; and

- Key informant interviews.

See Annex 2: Evaluation Methodology, for further description of each line of evidence.

Key findings

Relevance

| Expectations | Findings |

|---|---|

| Priorities of the program have adapted effectively to emerging Government of Canada and Parks Canada priorities, as applicable over the last five years | Evaluation findings highlighted the desire for guidance on collecting EI data related to climate change and how to collaborate with Indigenous partners to respectfully apply their knowledge within the program. |

| Ecological integrity measures developed by field units appropriately monitor ecological integrity indicators | An analysis of the survey and interview data both indicated that ecological integrity measures were a key area to be improved upon. |

| The ecological integrity indicators selected appropriately represent park ecosystems | An analysis of survey and interview data both indicated that ecological integrity indicators were generally representative of park ecosystems. The ratings assigned to ecological integrity indicators were an area of concern within the reporting framework, particularly with regards to the accuracy of such ratings. |

Inclusion of emerging priorities

Evaluation findings highlighted the desire for guidance on collecting EI data related to climate change and how to collaborate with Indigenous partners to respectfully apply their knowledge within the Program.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 1.

Considerations

Independent Working Group (IWG)

After the Minister of Environment and Climate Change's Round Table in 2017, the Minister called for the creation of a short-term independent working group.

The IWG was established in 2018. Part of its mandate was to provide recommendations on how to ensure that maintaining EI is one of the priority considerations in decision-making at Parks Canada (see Annex 1: Members of the IWG).

Emerging priorities

Survey results indicated that there is a strong desire among field unit staff for additional guidance on how to consider the effects of climate change and how to collaborate with Indigenous partners to respectfully apply their knowledge within the program. These two areas are supported by documentation in the following sections: Climate change and Indigenous ways of Knowing.

Climate change

In the 2019-20 Parks Canada Departmental Plans and Priorities, it was stated that Parks Canada would work toward implementing the recommendations of the 2019 IWG report. Related to climate change, it was recommended that "...Parks Canada adopt a flexible, adaptive management approach that addresses the shifting baselines that will result from climate change. This may mean that additional indicators are required to help establish the relationship between climate change and ecosystem integrity" (2019 IWG report, Section 3.1).

Indigenous ways of Knowing

The inclusion of Indigenous ways of Knowing is mentioned in the 2011 EIM Guidelines. On the subject of measures: "Measures that incorporate species of cultural importance or that are premised on historically monitored, culturally based ecological observations will serve to engage Aboriginal peoples in the cooperative management" (p. 14). * This quote is from a dated document and the Government of Canada (GoC) now uses the term Indigenous rather than Aboriginal.

EI measures

An analysis of the survey and interview data both indicated that ecological integrity measures were a key area to be improved upon.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 3.

Considerations

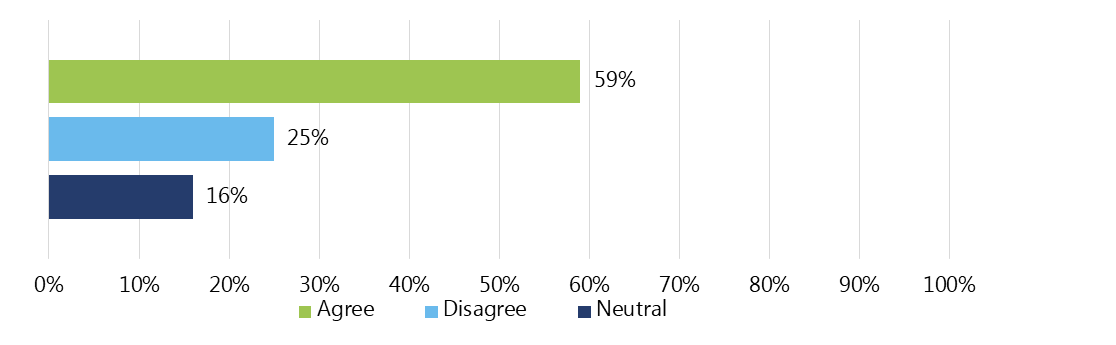

The survey results indicated that 25% of EIM scientists and program staff surveyed do not believe EI measures provide an accurate summary of EI indicators, while 16% are neutral (see Figure 3: Percentage of survey respondents who felt that EI measures enable an accurate summary of chosen EI indicators (n=64)).

Incorporating measures that can better detect trends in data with statistical power was stated as a key area for improvement. Of the 25% who did not believe EI measures provided an accurate summary of EI indicators, reasons included: inaccurate baseline data and thresholds; insufficient sample sizes for measures; inability to address issues arising from missing historical data; and the need for rigorous analysis of existing data.

The survey and interview data also found that having measures that collect data at only one or two locations within a park may not provide data that is representative of the ecosystem as a whole (particularly in larger parks).

Including measures that assess climate change and are reflective of Indigenous ways of Knowing, as well as the co-development of measures with input from Indigenous communities and knowledge holders, were noted to be areas that could help increase relevancy of EI measures in monitoring EI indicators.

Text description

A bar graph shows the percentage of respondents who rated their level of agreement for EI measures enabling an accurate summary of chosen EI indicators. Although the highest percentage of respondents agreed that EI measures enable an accurate summary of chosen EI indicators, a quarter of respondents disagreed.

Agree: 59% of respondents

Disagree: 25% of respondents

Neutral: 16% of respondents.

Baseline data

In the 2013 performance audit of EI in national parks conducted by the Office of the Auditor General, gaps were identified in baseline data for selected plant and animal species. An analysis of survey data indicated that challenges continue to persist in determining baseline conditions due to gaps in data.

Operational reviews

Since 2014, 17 operational reviews have been conducted by the EMD. They were seen to be very useful by resource conservation managers, as identified in interviews. Within the seven reports reviewed for the evaluation, EMD recommended adjustments such as: merging measures to better reflect indicators; improvement to thresholds; addition of measures to increase accuracy; and adding, deleting or combining measures, among others.

EI indicators

Table 3: Number of indicators monitored by park (2020)

An analysis of survey and interview data both indicated that ecological integrity indicators were generally representative of park ecosystems.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 3.

The 2011 EIM Guidelines emphasize that field units are to focus their monitoring efforts on three to four EI indicators. Limiting the number of indicators was meant to create a sustainable, long-term program and ensure that condition assessments of EI indicators are credible. See Table 3: Number of indicators monitored by park (2020).

| # of indicators monitored | % of parks |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2% |

| 2 | 26% |

| 3 | 65% |

| 4 | 7% |

Representativeness of indicators

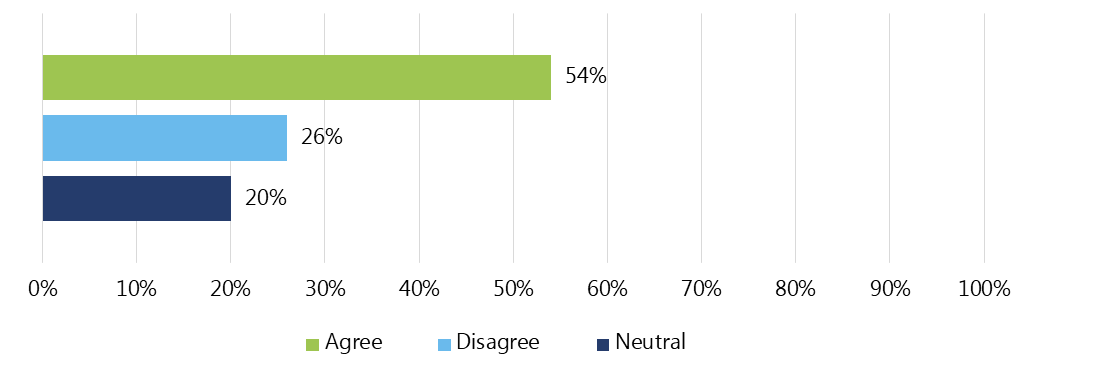

Parks Canada has had to strike a balance between indicator selection and resources available to adequately monitor them. Most staff interviewed and surveyed agree that the chosen EI indicators represent the most essential park ecosystems within their field unit (see Figure 4: Percentage of survey respondents who felt that EI indicators represent essential ecosystems (n=64)).

It was found that, due to various factors including the number of ecosystems available to measure within a park and the capacity of park staff to collect data, the majority of parks have chosen to collect data for three indicators (65%). See Table 3 below for further information. Approximately one quarter (27%) of resource conservation managers and EIM Program scientists and staff who responded to the survey felt that some ecosystems are currently being missed as a result of staffing considerations.

Other considerations included the desire for further inclusion of Indigenous ways of Knowing and guidance on how to address the impacts of climate change and the interconnectedness of landscapes within the data.

Text description

A bar graph shows the percentage of respondents who rated their level of agreement for EI indicators representing essential ecosystems. The highest percentage of respondents agreed that EI indicators represent essential ecosystems.

Agree: 75% of respondents

Disagree: 13% of respondents

Neutral: 13% of respondents

EI conditions

The ratings assigned to ecological integrity indicators were an area of concern within the reporting framework, particularly with regards to the accuracy of such ratings.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 3.

Considerations

EI conditions are the assessment of the health of ecosystems within a park. The EI measures and thresholds contribute to the EI indicator. The indicator is then assigned an EI condition rating (poor, fair or good). These ratings appear in State of the Park Reports (SOPRs) and are what Parks Canada commonly references for decision-making purposes. If deemed necessary by the field unit superintendent, it is possible for condition ratings to be assessed and corrected to better represent the overall condition of the ecosystem. For example, in Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq, Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik National Parks, Indigenous ways of Knowing contributed to SOPRs in addition to data on EI measures and thresholds.

Further details on how EIM data contributes to decision-making can be found in the section: EIM Program & decision-making.

Confidence among EIM Program scientists and staff is varied in regards to condition ratings accurately reflecting the states of ecosystems (see Figure 5: Percentage of survey respondents who felt that the ratings assigned to EI indicators accurately reflect the state of the ecosystems (n=61)).

Text description

A bar graph shows the percentage of respondents who rated their level of agreement for the ratings assigned to EI indicators accurately reflecting the state of the ecosystems. Levels of agreement varied among respondents.

Agree: 54% of respondents

Disagree: 26% of respondents

Neutral: 20% of respondents

Reported factors for varied confidence included:

- The rating system being overly simplistic for yearly reporting - the conditions and trends are considered to be definitive ratings even if they only represent a few measures within a complex ecosystem;

- Challenges extrapolating measures for the entire ecosystem (as discussed in the section: EI measures);

- Difficulties developing meaningful thresholds and missing data; and

- The reporting framework relying on a western approach to measuring data which does not reflect Indigenous ways of Knowing within the indicator conditions.

Coherence

| Expectations | Findings |

|---|---|

| Ecological integrity measures and indicators are consistent with international norms. | The 2011 Ecological Integrity Monitoring Guidelines are consistent with, and have helped to shape, international norms on ecological integrity. EIM data informs national biodiversity targets and helps illustrate Canada's contributions to the global framework and targets on conserving biodiversity. |

International contributions

The 2011 EIM Guidelines are consistent with, and have helped to shape, international norms on ecological integrity.

EIM data informs national biodiversity targets and helps illustrate Canada's contributions to the global framework and targets on conserving biodiversity.

Considerations

A benchmarking exercise revealed that the EIM Program at Parks Canada has helped shape international norms on EI. For example, the 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature's Ecological Restoration for Protected Areas: Principles, Guidelines and Best Practices (2012) was developed based on Parks Canada's EIM Guidelines.

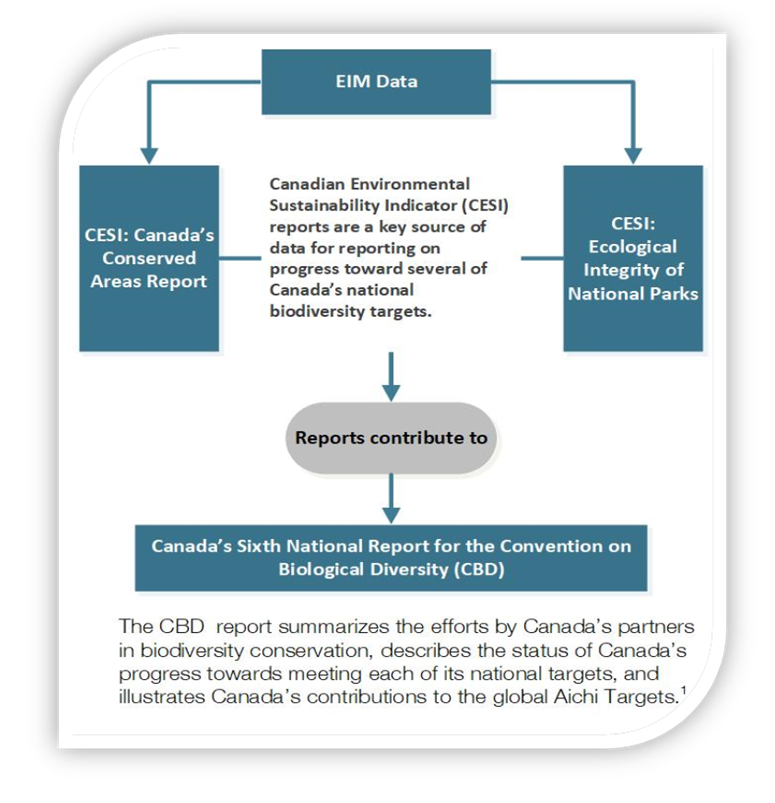

Parks Canada continues to contribute internationally by providing EIM data to inform national and international biodiversity targets. Figure 6 outlines the nature of the contributions of the EIM Program.

Text description

A flow chart shows the contribution of EIM data to international reports.

Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicator (CESI) reports are a key source of data for reporting on progress toward several of Canada's national biodiversity targets. EIM data contributes to two CESI reports: Ecological Integrity of National Parks and Canada's Conserved Areas Report.

These CESI reports contribute to Canada's Sixth National Report for the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The CBD report summarizes the efforts by Canada's partner's in biodiversity conservation, describes the status of Canada's progress towards meeting each of its national targets, and illustrates Canada's contributions to the global Aichi Targets.

Note: In 2010, a Strategic Plan for Biodiversity was adopted at the Conference of the Parties for the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. This plan includes 20 global biodiversity targets, known as Aichi Targets, which each party to the Convention has agreed to contribute to achieving by the year 2020.

1 In 2010, a Strategic Plan for Biodiversity was adopted at the Conference of the Parties for the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. This plan includes 20 global biodiversity targets, known as Aichi Targets, which each party to the Convention has agreed to contribute to achieving by the year 2020.

Effectiveness – Part I

| Expectations | Findings |

|---|---|

| Parks Canada reports on the ecological integrity of national parks to Canadians | Parks Canada provides EIM information to Canadians through a variety of online methods. EIM information is also provided for publicly available reports that reflect government priorities. |

| Parks Canada ecological integrity monitoring reporting is open and transparent | EIM data has been shared openly with the public in the Open Government Portal and SOPRs. |

| Ecological integrity monitoring information is made available to Parks Canada staff | EIM data has been made available to Parks Canada staff through the ICE web application. Field units have taken the initiative to create additional reports. |

| Ecological integrity monitoring information is timely and accurate | Changes currently underway to improve the ICE web application could improve data accuracy, availability and timeliness. |

| Common understanding and consistent application of ecological integrity monitoring throughout Parks Canada | Survey, document review and key informant interview analysis revealed that the current Ecological Integrity Monitoring Guidelines (2011) are clearly understood. There was low awareness of a second set of guidelines specific to northern parks. |

| Indigenous ways of Knowing are integrated into ecological integrity monitoring in national parks. | Efforts have increased in recent years to develop ecological integrity measures and indicators informed by Indigenous ways of Knowing, however, there remains room for improvement. |

Reporting on EIM Data

Parks Canada provides EIM information to Canadians through a variety of online methods. EIM information is also provided for publicly available reports that reflect government priorities.

The EIM Program has a large data set that has the potential to be of great value to inform Canadians on biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and a changing climate (Independent Working Group, 2019).

Considerations

Reporting to Canadians

Communication with the Canadian public about EIM information occurs in a several ways:

On the EI of national parks:

- EIM ecosystem trend assessments contribute to the reporting of the corporate target of "92% of ecosystems maintained or improved" indicator that is featured in Parks Canada's annual Departmental Results Report and GC InfoBase.

- A full review of SOPRs indicated about half (47%) of field units share their SOPRs online.

The Information Centre on Ecosystems (ICE) web application provides EIM data that is included in publicly available reports that reflect government priorities (i.e., Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS), Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy (DSDS), Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators (CESI)), as well as in the EI in Canada's National Parks Report (2005).

Table 4: Review of available State of the Park Reports, is based on information available and reviewed during 2021 and based on the scope of the evaluation up to 2020. SOPR assessments are undertaken every five years to identify key management issues to address in the next Park Management Plan (PMP).

| SOPRs available | From 44 national parks* | 94% of parks reviewed have a SOPR |

| SOPRs updated within five years of 2020 | From 37 national parks | 79% of parks reviewed have a SOPR updated within five years of 2020 |

| SOPRs available on the web | From 22 national parks | 47% of parks reviewed have a SOPR available on the web |

| SOPRs available on the web & updated within five years of 2020 | From 6 national parks | 13% of parks reviewed have a SOPR available on the web and updated within five years of 2020 |

*The scope of the evaluation did not include Rouge National Urban Park.

Note: A SOPR was not available in 2020 for Akami-Uapishkᵁ-KakKasuak-Mealy Mountains National Park Reserve, Qausuittuq National Park, or Thai Dene Nene National Park Reserve.

Open & transparent reporting

EIM data has been shared openly with the public in the Open Government Portal and SOPRs.

Considerations

It was found that EIM data was shared with the public through the Open Government Portal. EI condition ratings are also shared online through available SOPRs.

Open Government Portal

With 465 datasets included from Parks Canada in the Open Government Portal, it is estimated that 445 were uploaded by the EIM Program. The EMD continues to support updates and new publications, although there are no funds or requirements assigned.

State of the Park Reports

The 2013 Management Planning and Reporting Directive did not require field units to make SOPRs available on the web.

In the progress report addressing recommendations from the Minister's Roundtable (2017), one of the commitments made by Parks Canada was to: "...produce State of the Park reports for each park every five years that are publicly available for review by scientists, public and other interested parties." Close to half (46%) of parks have now made their SOPRs available online (as of December 2020).

Data available to Parks Canada staff

EIM data has been made available to Parks Canada staff through the ICE web application. Field units have taken the initiative to create additional reports.

Considerations

Information Centre on Ecosystems

Information about the EIM Program, including associated datasets, are available to staff through the Information Centre on Ecosystems (ICE) internal web application. This includes some automated reports that provide structured data to assist in national-level reporting (improvements being made to the ICE web application will be discussed in the section: Timeliness & accuracy of EIM data).

Additional reports

The majority of survey respondents (65%) indicated that their field unit does produce reports summarizing EIM data.

Examples include: individual summary reports for EI measures; annual or bi-annual resource conservation manager field reports; annual summary reports for partners or stakeholders, etc.

Time constraints and limited staff resources/budgets were indicated to be the most common barriers to producing reports, particularly for co-management partners or local communities.

Timeliness & accuracy of EIM data

A review of the Information Centre of Ecosystems (ICE) web application, document review and key informant interviews indicated that the changes currently underway to the web application could improve data accuracy, availability and timelines.

Considerations

Reports produced by ICE

ICE includes some automated reports that help the EMD and other divisions with national program responsibilities to produce periodic program reports. There are limitations in the structure and function of ICE that can lead to occasional errors in automated reporting, particularly for parks that do not follow the typical monitoring approach.

Situated within PAEC, the Conservation Information Management (CIM) team is responsible for the ICE web application as well as guidance documents and training. At this time, the team is considering the issues related to the current ICE web application and is seeking input from EMD and other relevant teams at Parks Canada regarding the "Renewal Options Analysis" draft in order to best leverage the success of ICE and to make improvements where needed.

The EMD reviews ICE outputs and makes corrections as needed before including the data in formal reporting (i.e., ecosystem condition and trend assessments).

Improvements

Since 2019, the Power BI data visualization software has been used, which has given the CIM team more direct access to improve and develop automated system reports.

Additional staff were hired in the fall of 2021 for the purpose of creating better reports through data quality control and data cleaning. This work continues and should improve the accuracy of automated reports moving forward.

Data input

Field unit superintendents and resource conservation managers are accountable for ensuring the integrity and timeliness of data their field units are documenting in the ICE web application.

Although the accuracy of data inputted at the field unit level was out of scope for the evaluation, when asked about guidance from EMD in maintaining up-to-date information within the ICE web application, 57% of survey respondents indicated that they had received appropriate guidance.

Data accuracy

Data accuracy in ICE was reported to be affected by:

- Limitations in the structure of the web application and functions of the application;

- The values presenting as "errors" if specific considerations are needed (i.e., narrative comments); and

- Incomplete or inconsistent data entry.

Clear EIM Guidelines (2011)

Survey, document review and key informant interview analysis revealed that the current EIM Guidelines (2011) are clearly understood. There was low awareness of a second set of guidelines specific to northern parks.

Considerations

The 2011 EIM Guidelines clearly outline how to choose indicators and develop measures, thresholds and condition ratings using a scientifically rigorous method. As they are guidelines, these are suggested methods but are not enforced.

EIM Guidelines (2011)

Overall, 64% of survey respondents agreed that appropriate guidance is received from the EMD for implementing the existing EIM Guidelines (2011) within field units. Respondents noted that guidance is provided in developing and updating EI measures and entering data within the Open Data Portal. This support was indicated to be available, sufficient, helpful and consistent.

Operational reviews conducted by the EMD team (17 completed since 2014) were seen to be very useful for those field units who received one. In the seven reports reviewed for the evaluation, EMD recommended adjustments such as: merging measures to better reflect indicators; improvement to thresholds; addition of measures to increase accuracy; and adding, deleting or combining measures, among others.

Northern Parks Guidelines (2010)

There was also a set of Northern Parks Guidelines developed in 2010, with a target implementation date of 2014. These guidelines outlined actions for Parks Canada to take in order to complete the development and successful implementation of core EI monitoring plans and activities within the northern bioregion by March 2014. The Northern Parks Guidelines were meant to address issues faced by northern parks and include: the geographic scope of monitoring, partnering, community-based monitoring, outreach and the role of Indigenous ways of Knowing. Survey and interview findings revealed that there was low awareness of the Northern Parks Guidelines.

Indigenous ways of Knowing and the EIM Program

Efforts have increased in recent years to develop ecological integrity measures and indicators informed by Indigenous ways of Knowing; however, there remains room for improvement.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 2.

Considerations

IWG report (2019)

One of the recommendations made by the IWG in a 2019 report to the Minister was to "…engage local Indigenous governments in developing ecological integrity indicators informed by Traditional Knowledge and incorporate them into the related monitoring program" (accessed on web February 30, 2021, Section 3.1. Ecological Integrity).

The evaluation found that, at the field unit level, there are efforts being made to reflect Indigenous ways of Knowing in the current structure of the EIM Program, as recommended by the IWG.

Some examples include:

- Field units collaborating with Indigenous partners in the development and data collection of specific measures (i.e., the Muskrat measure for Wood Buffalo National Park);

- Inuit Knowledge Working Groups have been developed. These provide guidance and advice on how to appropriately reflect Inuit knowledge in measures and indicators; and

- The development of separate data storage options for recording Inuit knowledge. For example, the Sirmilik National Park Pilot Project recorded data outside of the ICE web application in a spreadsheet. This data included observations, notes and recordings, photos, etc.

Room for improvement

The document review, survey and key informant interviews found that there remain some barriers to reflecting Indigenous knowledge ways of knowing in the EIM Program.

Indigenous ways of Knowing are sometimes included as a narrative summary in the ICE web application. However, ICE-based algorithms do not incorporate qualitative data and thus this data is not considered in the data roll-up.

For example, a search for measures in the ICE web application based on Indigenous ways of Knowing yielded results for four national parks: Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq, Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik. Within these search results, Indigenous ways of Knowing measures were either not yet developed/assessed or used narrative descriptions of data instead of assigning ratings. As such, Indigenous ways of Knowing were not reflected in ecosystem (indicator) condition ratings in ICE reports during the timeframe of this evaluation (2015-2020).

Effectiveness – Part II

| Expectations | Findings |

|---|---|

| Ecological integrity condition monitoring information supports evidence-based decision-making | It was found that EIM data has contributed to key documents used for decision-making at Parks Canada. Survey and interview analysis indicated that EIM data is used for submissions for short-term funding envelopes (i.e., CoRe). Due to the long-term nature of data collected, some resource conservation managers felt it was difficult to use the information for short-term management decision-making. |

| Collaboration and co-ordination with relevant stakeholders on ecological integrity condition monitoring contributes to landscape-scale conservation | There have been efforts to incorporate landscape-scale monitoring into the EIM Program. An analysis of survey and interview data indicated that collaboration with stakeholders has occurred; however, the EIM Program has not coordinated defining, developing or maintaining these collaborations. |

| Decision-making is grounded in collaborative approaches that reflect both Indigenous and western knowledge | There are areas for improvement in raising the profile of Indigenous ways of Knowing within the EIM Program. |

The EIM Program & decision-making

Through document review and interview analysis, it was found that EIM data has contributed to key documents used for decision-making at Parks Canada.

Survey and interview analysis indicated that EIM data is used for submissions for short-term funding envelopes (i.e., CoRe).

Due to the long-term nature of data collected, some resource conservation managers felt it was difficult to use the information for short-term management decision-making.

Decision-making documents

Park Management Plans

A Park Management Plan (PMP) is a strategic and long-term guide for future management of a national park. It serves as the primary accountability document for each national park and its primary goal is to ensure that there is a clearly defined direction for the maintenance or restoration of EI and, in the light of this primary goal, for guiding appropriate use.

The first step of the planning process is the production of a State of the Park Report (SOPR), which describes the state of the ecosystem within a park, as well as the progress made toward achieving the goals of the PMP. SOPRs include a condition rating of park indicators (ecosystems) as either poor, fair or good. These ratings help define targets, which drive planning and decision-making in many parks.

The EIM condition rating contained in the SOPRs is in turn used by some field units for decision-making through PMPs. These are used to inform planning on a 10-year cycle. A review of PMPs indicated that EIM data was directly referenced in more than half (67%) of PMPs.

Impact Assessments (IA)

All Parks Canada proposed projects that are likely to result in adverse environmental effects must undergo an Impact Assessment (IA). IAs look into the project's interactions with the environment and its potential to cause significant adverse environmental effects (e.g., alter/impact/affect the EI).

There are two categories of IA: Basic Impact Assessments and Detailed Impact Assessments.

Basic Impact Assessments (BIA)

BIAs are applied when potential adverse environmental effects are predictable, will be confined to the project site or immediate surroundings, and mitigation measures are well-established.

BIAs are a tool used, when appropriate, to assess the potential EI impact of new projects (i.e., infrastructure) within parks. If the scale of a project is small, it may not be possible to determine the potential impact on EI within the park as a whole. The scale of a project therefore helps to determine whether it is necessary or useful to include EI data.

Detailed Impact Assessments (DIA)

A DIA is the most comprehensive level of impact assessment, as it focuses on the effects of projects on the natural resources that reflect the EI of the park and takes into account the active management targets for EI. DIAs facilitate decisions on potentially significant adverse environmental effects.

DIAs have not incorporated EIM data in a systematic way. However, the recently updated Detailed Impact Assessment Handbook (published in 2021) will require the inclusion of EIM data moving forward for projects related to EI.

Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA)

SEAs enable early consideration of potential environmental effects during the development of policies, plans or programs. A SEA is required by a Cabinet Directive for a proposed policy, plan or program that requires Cabinet or Ministerial approval and may result in important environmental effects, either positive or negative.

SEAs contribute to decision-making by ensuring PMPs identify actions to maintain or restore Valued Components (other potential Valued Components include Species at Risk, World Heritage Sites and Additional Valued Components) over a span of 10 years.

The review of sample SEAs demonstrated that two of the three included EIM data as a Valued Component, thus including all EI data from the park in the assessment (i.e., measures, thresholds, indicators, condition ratings).

There were large variations expressed by resource conservation managers on whether EIM data is useful for decision-making. It was noted that EIM data is used to inform Species at Risk (SAR) and Conservation and Restoration (CoRe) projects as well as Fire Management. However, as the EIM Program provides medium and long-term data, some managers felt it was difficult to use the information for short-term management decision-making.

Conservation and Restoration (CoRe) Program

Through the CoRe program, Parks Canada invests approximately $15M each year in innovative and collaborative projects to restore ecosystems in national parks, contribute to ecological sustainability in national marine conservation areas and recover species at risk at all Parks Canada administered sites.

Data from the EIM Program is used to obtain funding from the CoRe program. Project submissions are given a score out of 50 for EI relevance. All 10 reports reviewed that were submitted after 2017 had EI scores. Most were at the high end, scoring 40 points out of 50. These higher score submissions were generally related to SAR projects. It should be noted that prior to 2017, CoRe projects were not scored on EI data.

According to the 2020-21 internal CoRe Report Summary, 88% of ongoing projects that year supported Nature Legacy's Pillar 1 – Ecological Integrity.

Species at Risk

The Species at Risk Act (SARA), proclaimed in June 2003, helps Canada meet its international commitments under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Under SARA, Parks Canada has two key roles: supervising the planning of species recovery efforts and protecting species and their habitats located in areas administered by Parks Canada, i.e., in national parks, national historic sites and national marine conservation areas.

EIM data informs Parks Canada's efforts to meet the requirements of SARA. Within the ICE web application, there is a "SARA or Other Associated Species" field under each measure where relevant information may be inputted. Measures identified in the EIM Program are assessed by the SARA team to determine if they may fit within the population and distribution objectives in the SARA multi-species action plans.

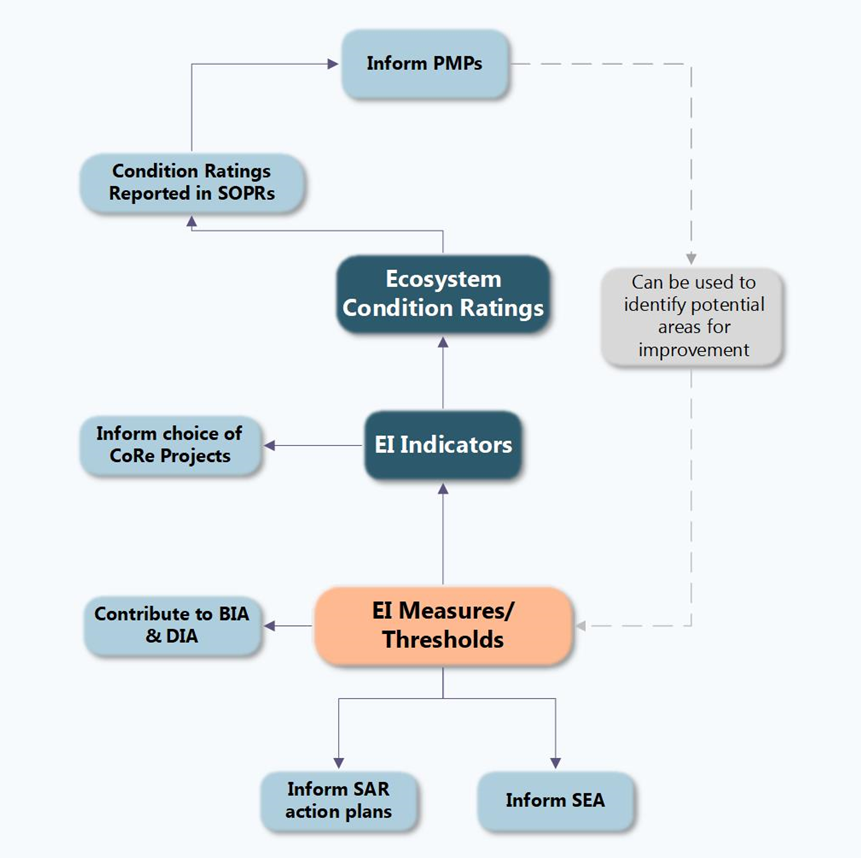

Figure 7 represents EIM contributions to decision-making at Parks Canada.

Text description

A flow chart illustrates the points where EI data contributes to decision-making.

The flow chart starts with EI measures and thresholds, which are indicated to inform SAR action plans, SEAs and to contribute to BIAs and DIAs. The flow then goes from EI measures and thresholds to EI indicators.

EI indicators contribute to informing the choice of CoRe projects. The status of EI indicators are also used to develop ecosystem condition ratings.

Ecosystem condition ratings are reported in SOPRs, which then inform the development of PMPs. The last connection indicates that PMPs can be used to identify potential areas for improvement of the EI measures and thresholds.

Landscape-scale monitoring

There have been efforts in field units to incorporate landscape-scale monitoring into the EIM Program.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 1.

Considerations

Program statement

As stated on the EI section of the Parks Canada website: "National parks are part of larger ecosystems and must be managed in that context. Parks Canada recognizes the need to integrate parks into their surrounding landscapes so that parks function as part of a connected network."

Remote sensing

Landscape-scale monitoring using remote sensing tools is mentioned in the 2011 EIM Guidelines, and is encouraged where feasible, in the development of landscape-scale measures as well as in northern parks where "a well-designed remote-sensing program will be the cornerstone of monitoring for park EI."

Although not all technology used within the program is used to advance landscape-scale monitoring, a very large percentage (91%) of field unit staff quoted using technology to help with EIM data collection, and just under a quarter of the examples provided were of remote sensing.

In addition, the collaboration and coordination efforts of the EMD focus on landscape-scale monitoring using remote sensing.

Examples include:

- Collaborating with ECCC for remote sensing; and

- Receiving data from the Canadian Space Agency to aid in the development of Parks Canada's satellite measures.

Additional efforts

Case studies highlighted how field units are developing ways to increase landscape-scale monitoring in the EIM Program. For example, by using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to map out landscapes to increase accuracy of measures and to identify potential areas where further collaboration outside of park boundaries could be beneficial.

Survey and interview data indicated that many stakeholder collaborations focus on landscape-scale conservation. Examples include:

- The EMD collaborating with a number of provincial governments; and

- Collaborations through EMD are taking place in the area of forest indicator development with Natural Resources Canada (NRCan).

Stakeholder collaboration

An analysis of survey and interview data indicated that collaboration with stakeholders has occurred; however, the EIM Program has not coordinated defining, developing or maintaining these collaborations.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 1.

Considerations

Collaboration

Data indicated that many collaborations occur with external stakeholders (see list below). Collaboration was seen to be particularly useful for data sharing, as well as helping to inform the development of a landscape-scale/connectivity and bioregional approach to the program. Landscape-scale monitoring and ecological connectivity are of particular importance as these are current priorities for Parks Canada.

External stakeholders interviewed indicated that Parks Canada is widely seen as an effective and beneficial partner in the field of ecological integrity monitoring. Field-level relationships are described as positive and leveraged when necessary.

The program does not, however, coordinate defining, developing or maintaining these collaborations. There is a desire for more structured and regular engagement with stakeholders where appropriate. For example, external stakeholders felt that the lack of formal collaboration agreements led to the dissolution of relationships as ecologists/researchers moved into new roles or retired.

Most frequently reported collaboration partners:

- Federal government (i.e., ECCC, DFO, NRCan);

- Provincial/territorial governments;

- Academia;

- Indigenous communities; and

- NGOs.

Data

Coordination of data occurs at the field unit level across a variety of sectors including: federal government (ECCC, DFO), provincial and territorial governments and to a lesser extent with academia. Field units are coordinating with partners to obtain data that feeds into data collection for measures. For example, the Atlantic Field Unit relies heavily on academic partners and data sharing agreements with DFO, ECCC (i.e., SAR data, water quality, meteorological station data, hydrometric data) and NGOs to support their EIM measures.

Barriers

The focus on collecting EI data with the purpose of landscape-scale monitoring and connectivity is a more recent (within the last 5 years) focus for Parks Canada. As a result, funding has been made available to explore collaborations (i.e., Nature Legacy funding), which field units are taking advantage of.

For those who indicated that their field unit does not collaborate with stakeholders, some barriers included the difficulty in including collaborative data within EI measures and the nature of geographic location for some parks.

Collaborative approaches – Indigenous Ways of Knowing

There are areas for improvement in raising the profile of Indigenous ways of Knowing within the EIM Program.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 2.

Considerations

Importance of Indigenous ways of Knowing within the Program

The 2011 EIM Guidelines highlight the importance of Indigenous ways of Knowing within the program with the following guidance: "Park managers are responsible for ensuring that traditional Aboriginal knowledge is part of the knowledge base used to inform decision-making, and for reporting park condition" (p. 14). * This quote is from a dated document and the GoC now uses the term Indigenous rather than Aboriginal.

The guidelines go on to provide examples of reflecting Indigenous ways of Knowing in the assessment of measures and indicators, or by including it in the State of the Land section of the SOPR.

Two-eyed seeing

The EI page on the Parks Canada website states that: "Ecological integrity should be assessed using science and Indigenous ways of Knowing. These perspectives allow a deeper understanding known as 'two-eyed seeing'" (accessed online July 12, 2022).

The two-eyed seeing approach (Figure 8) is often premised on looking at problems, research questions and research needs with the eyes of two (or more) knowledge systems (Operationalizing Ethical Space and Two-Eyed Seeing in Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas and Crown Protected and Conserved Areas p. 7)

Text description

This figure is a visual representation of the two-eyed seeing approach. The graphic shows two eyes.

The left eye represents Indigenous knowledge systems. The key strengths indicated are: lived knowledge, place-based, holistic, connected to legal traditions, and extended oral archives.

The right eye represents western knowledge systems. The key strengths indicated are: scientific method, common principles, highly specific, repeatable, and measurement tools.

At the bottom of the graphic, there is a list of the key strengths of co-existence. These are indicated to be: mutual research interests; research and co-development; shared recognition and co-benefits; wider set of tools and archival data; and, a holistic conception of success.

Current efforts

There is some progress being made in this regard. These are highlighted in the following section.

Recent advancements

The 2011 EIM Guidelines suggest that park managers are responsible for ensuring Indigenous ways of Knowing are part of the knowledge base to help inform decision-making and for reporting park condition. The Guidelines state: "SOPRs include the local Aboriginal perspective on the state of the land in the park, as well as the state of their connection to the land." * This quote is from a dated document and that the GoC now uses the term Indigenous rather than Aboriginal

There are attempts being made within several field units to raise the profile of Indigenous ways of Knowing in informing the knowledge of park ecosystems (i.e., Nunavut FU, Southwest Northwest Territories FU). One such example is described in the Case study highlight (see below).

Case study highlight Collaborative projects with Indigenous partners have helped strengthen more meaningful involvement in decision-making processes, and the sharing and integration of Indigenous ways of Knowing has helped to better inform and improve the EIM Program. For example, a summary of Indigenous ways of Knowing was included in Auyuittuq's 2019-20 SOPR. This was the first time that both Indigenous ways of Knowing and scientific information were used to assess the state of that park's EI. Another example is in Wood Buffalo National Park where Indigenous partners and government stakeholders are jointly developing a new, integrated monitoring program for the Peace Athabasca Delta (PAD). The PAD muskrat survey will be included under that monitoring program and will continue as part of the park's EIM Program.

Areas for improvement

The evidence demonstrates that Indigenous ways of Knowing have not been considered as equal to western knowledge in the program. Firstly, as referenced in a section of this report (Indigenous ways of Knowing and the EIM Program), the ICE algorithms that roll-up data do not reflect the qualitative Indigenous data that is included by field units in the web application. Secondly, Indigenous ways of Knowing related to park EI condition is rarely included in SOPRs. Lastly, there is no clear system to work with knowledge holders to reflect Indigenous ways of Knowing, Indigenous values or the information that is valued in these communities.

Indigenous ways of Knowing were underrepresented in the SOPRs reviewed (refer to Table 4: Review of available State of the Park Reports). Overall, references to Indigenous ways of Knowing were not directly related to EIM but rather were related to other areas such as cultural activities, harvesting projects, etc. This has created a potential area for improvement in regards to reflecting Indigenous ways of Knowing in the knowledge base used for reporting on park conditions.

Nature Legacy

Nature Legacy is an interdepartmental initiative announced in Budget 2018 that aims to protect Canada's biodiversity, ecosystems and natural landscapes. It was renewed in Budget 2021 for an additional five years.

At Parks Canada, the initiative is meant to provide enhanced capacity and resources to deliver its mandate and to modernize its approaches to conservation. In particular, Nature Legacy aims to strengthen Parks Canada's system of protected areas and cement them as cornerstones in an ecologically connected landscape.

The initiative also emphasizes the importance of building strategic partnerships with Indigenous peoples, other levels of government, non-governmental organizations, academia, industry and others.

Recent advances

It was found that there is a desire within field units to build relationships with Indigenous communities and governments with respect to EIM reporting. For example, the survey highlighted that some field units are collaborating with Indigenous partners (largely through CoRe and Nature Legacy initiatives) to determine how Indigenous ways of Knowing can obtain equal footing with data currently collected for the EIM Program.

Engagement with Indigenous partners has improved in recent years because of a renewed focus by the program on landscape-scale/connectivity conservation. Of note, key informant interviews and survey respondents indicated that Nature Legacy funding allowed more collaborative approaches with Indigenous peoples to take place. One of the areas that Nature Legacy emphasizes is the importance of building strategic partnerships with Indigenous communities. These partnerships could help inform future data collection.

Efficiency

| Expectations | Findings |

|---|---|

| Program resources are optimized in order to efficiently deliver activities | The survey, case studies and interviews highlighted that technology has contributed to enabling some parks to expand the geographic area from which data is collected. It has also allowed for more precise measurements. The survey and interview data indicated that there is room to provide additional guidance to encourage efficiencies within the EIM Program. There were resource constraints noted, particularly in northern and smaller parks. |

Data collection

Technology has contributed to enabling some parks to expand the geographic area from which data is collected. It has also allowed for more precise measurements.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 4.

Considerations

Technology

Survey analysis found that remote sensing, aerial photography and remote cameras were the most commonly used types of technology to help with data collection (see Figure 9: Types of technology used to aid EIM data collection). The case studies and document review found that automation and technology is aiding field units in collecting more precise measurements and increasing their ability to monitor larger areas. As advances in technology are made and become more widespread, tools such as satellite and drone imagery could be used as tools for EIM data collection.

The survey and interview results indicated that current limitations include that data collection using technology can be labour intensive, time consuming and costly at the start. The capacity within the program to maintain and analyse data collected using technology in the long-term is also a consideration. Further data is required to determine if long-term savings outweigh the up-front costs.

Text description

A bar graph illustrates the most commonly used types of technology used for data collection based on the survey analysis.

Remote sensing: 24%

Arial photography: 19%

Remote camera: 19%

Autonomous recording units: 13%

Data loggers (i.e., water): 10%

Other (i.e., apps/tablets): 15%

Case study highlight: Ivvavik National Park

The Northern Parks Guidelines encouraged northern parks to incorporate remote sensing into their EIM programs. Remote sensing has provided benefits for some northern parks. For example, following the piloting of remote cameras, Ivvavik grizzly bear monitoring data has been recorded on an annual basis in the ICE web application since 2019 and has been reported in the park's SOPR. The remote camera information could provide supplemental data for other monitoring projects (e.g., snow coverage) or for future measures (e.g., landscape vegetation cover).

Park staff are rarely able to access these remote areas; therefore, having wildlife images and videos provides an opportunity to share them with the public. This external relations piece was an unexpected but valuable benefit of the monitoring.

Citizen science

Over half of survey respondents (56%) indicated that their field unit uses volunteers to help with EIM data collection. Although it was seen to have potential benefits to Parks Canada for other reasons (i.e., increasing public awareness and interest), it was found that citizen science initiatives do not always produce reliable EIM data. In addition, there are often planning considerations such as volunteer training and coordination that are required before allowing volunteers to collect data.

Program coordination

The survey and interview data indicated there is room to provide additional guidance to encourage efficiencies within the EIM Program.

This finding is addressed in Recommendation 4.

Considerations

IWG report (2019)

In the 2019 report from the IWG to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, it was recommended that "Parks Canada fully implement its ecological integrity monitoring program, in particular the collection of remote sensing and year-round data."

Guidance

As stated in the previous page, remote sensing was the most frequently used type of technology to help collect EIM data. There is work being done within the EMD to provide field units with guidance in this respect. For example, the EMD is co-chairing an informal working group on remote sensing of various ecosystems and on glacier monitoring.

Bioregional groups

Previous bioregional groups were seen as useful by staff but have not existed since 2012. In the 2011 EIM Guidelines, bioregions were stated as geographically related groups of parks that work together to develop common measures and protocols. According to the Guidelines, the success of the program heavily depends on the level of cooperation developed within bioregions.

Coordination

In addition to the bioregional groups, prior to 2009, there were bi-annual gatherings of field staff (ecologists and resource conservation managers) to present on EIM.

There is currently no formal method for field units to coordinate approaches to managing the EIM Program amongst each other. As a consequence, field units felt there is an opportunity to share information that would help reduce duplication of effort.

Some examples of desired areas for support/coordination include:

- Assessing scientific rigour;

- Determining common measures between parks;

- Increasing participation in programs such as WildTrax (bird monitoring) amongst parks;

- Increasing ability to compare data across parks

- Remote sensing;

- Improving/developing indicators, measures and thresholds;

- Methods to record changes associated with climate change impacts; and

- Reflecting Indigenous ways of Knowing in reporting.

Resources

There were resource constraints noted, particularly in northern and smaller parks.

Considerations

Resources

There were a few areas where resource constraints were noted. For example, survey respondents indicated that limited time and capacity, including staff and funding varies dramatically between parks and field units which makes it challenging to deliver the same quality of EI monitoring across parks. This is particularly an issue for northern parks given their complex logistics and extensive sizes.

In addition, it was found in the interviews that smaller parks struggle with capacity and time constraints during the operational season as a result of having only small teams available to collect data. Field units are balancing time, effort, conflicting priorities and limited resources. Furthermore, interviewees stated that the funding provided is sufficient only for current activities associated with data collection, leaving limited resources available for additional program activities (i.e., collaboration efforts, analysing data collected using technological tools).

The findings of the evaluation support those in the 2019 report by the IWG. The report found that: "Parks Canada is currently not monitoring and reporting all ecological integrity indicators, and field unit managers emphasized the need for year-round capacity to do so. There is often a difference between national parks – some of which fully report their indicators while others are challenged to monitor and report" (accessed online February 30, 2021, Section 3.1. Ecological Integrity).

Funding

A-base funding has increased by 5% over five years (2015-16 to 2019-20) while B-base funding has increased by 14% over those same five years (see Table 5 below). The top three categories submitted by field units as B-base funding were: funding for salaries, operating costs for new parks and sites and operating costs for Nature Legacy projects. Interestingly, the majority of B-base funding that was used for Nature Legacy was in the areas of ecological connectivity and building relationships with Indigenous peoples (see sections: Conservation and Restoration (CoRe) Program, Stakeholder collaboration and Collaborative approaches – Indigenous Ways of Knowing for additional information on usage of Nature Legacy funding within the EIM Program).

| Fund Name | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | Average Growth over 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-base | 11,997 | 13,169 | 13,318 | 15,071 | 14,276 | 5% |

| B-base | 4,812 | 3,625 | 3,575 | 5,898* | 6,987 | 14% |

*First year Nature Legacy funding was available.

Source: collated data provided by Parks Canada's Financial Directorate

Recommendations and management response

Recommendation 1

The Vice-President, Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation, should co-ordinate with the Senior Vice-President, Operations on an approach to integrate Parks Canada priorities into Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program guidance, with particular consideration to:

- Whether/how the continuing changes in ecosystems as a result of climate change should be addressed within ecological integrity measures, thresholds, and/or indicators; and

- The role that stakeholder and partner engagement should play in the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program and the structure of this engagement as it relates to landscape-scale conservation/connectivity.

For key findings related to the above recommendation, please refer to the following sections:

- Emerging priorities – Climate change

- EI measures – Considerations

- EI indicators – Representativeness of indicators

- Landscape-scale monitoring

- Stakeholder collaboration – Collaboration

Management Response

Agreed. Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate will work with Operations on an approach to further integrate new Parks Canada priorities into ecological integrity monitoring guidance.

| Deliverable(s) | Timeline | Responsible position(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Co-develop an approach determining whether and how climate change should be addressed in the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program. | March 2024 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 1.2 Co-develop an approach determining the role of external stakeholders as it relates to landscape scale conservation in the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program. | September 2024 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 1.3 Review, revise and integrate new guidance in the Guidelines of Ecological Integrity Monitoring. | March 2025 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

Recommendation 2

The Vice-President, Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation, in collaboration with the Senior Vice-President, Operations, and the Vice-President, Indigenous Affairs and Cultural Heritage, should work with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis to develop a Parks Canada wide approach where both Indigenous ways of Knowing and western knowledge are considered equally to inform the health of ecosystems.

For key findings related to the above recommendation, please refer to the following sections of this report:

- EI measures, indicators and conditions – Considerations

- Indigenous ways of Knowing and the EIM Program

- Collaborative approaches – Indigenous ways of Knowing

Management Response

Agreed. The Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate will collaborate with Operations and the Indigenous Affairs Branch to work with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis to co-develop approaches where both Indigenous ways of Knowing and western knowledge are considered equally to inform the monitoring and reporting of the health of ecosystems.

| Deliverable(s) | Timeline | Responsible position(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Engage with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, at both the national and local level. | March 2024 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 2.2 Co-develop flexible approaches which consider equally Indigenous ways of Knowing and western knowledge to inform the health of ecosystems. | March 2025 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 2.3 Implement co-developed approaches into ecological integrity program guidance and policy. | September 2025 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

Recommendation 3

In order to promote the continuous improvement of the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program, the Vice-President, Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation, should work with the Senior Vice-President, Operations, to examine and provide guidance on the ecological integrity data framework. Particular consideration should be given to:

- Expanding the use of operational reviews, or developing alternate methods of exploration, to examine the relevance of ecological integrity measures and thresholds in monitoring ecological integrity indicators;

- Whether the number of locations where ecological integrity measurements are collected provides sufficient information to represent the state of an indicator, particularly in large and northern parks; and

- Whether ecological integrity condition ratings sufficiently reflect the complexity of the ecosystems they are meant to represent, taking into consideration both western and Indigenous ways of Knowing.

For key findings related to the above recommendation, please refer to the following sections of this report:

- EI measures

- EI indicators

- EI conditions

Management Response

Agreed. The Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate will collaborate with Operations to examine and provide guidance for continuous improvement of the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program, in line with available resources.

| Deliverable(s) | Timeline | Responsible position(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Review and revise tools to assess relevance of ecological integrity measures and thresholds, and the quality of survey designs. | March 2024 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 3.2 Implement revised tools to support improvement of ecological integrity monitoring programs. | September 2024 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 3.3 Review and revise ecosystem assessment approaches, and integrate new assessment approaches into the updated Ecological Integrity Monitoring Guidelines. | March 2025 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

Recommendation 4

In order to promote program efficiency, the Vice-President, Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation, and the Senior Vice-President, Operations, should:

- Provide field units with centralised guidance on how to use technological tools related to data collection (i.e., remote sensing, remote cameras) while also ensuring that internal resources and expertise are assigned in each field unit to manage the tools; and

- Implement a formal mechanism for field units to communicate and collaborate when seen as beneficial.

For key findings related to the above recommendation, please refer to the following sections of this report:

- Data collection – Technology

- Program coordination – Bioregional groups

Management Response

Agreed. The Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate and Operations will continue to work together to promote program efficiency on an ongoing basis, in line with available resources.

| Deliverable(s) | Timeline | Responsible position(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 4.1 Develop and implement a formal collaboration mechanism among field units, to be used when beneficial. | March 2024 | Regional Executive Directors, Operations, led by Nature Legacy Advisors Network. Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 4.2 Develop standardised guidance on the use of technological tools for data collection related to ecological integrity monitoring. | March 2025 | Director, Conservation Programs Branch, PAEC |

| 4.3 Ensure that internal resources and expertise in both official languages are assigned in each field unit to manage technological tools, in line with available resources. | March 2025 | Field unit superintendents, Operations, led by resource conservation managers in field units |

Annexes

Annex 1: Members of the Independent Working Group to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change and Minister responsible for Parks Canada

IWG Members

The Working Group was comprised of a chair and six members that were chosen by the minister. These biographies are those that appear in the 2019 Report.

Peter Robinson — chair

Peter Robinson began his career as a park ranger working in wilderness areas across British Columbia, where he was decorated for bravery by the Governor General of Canada. After his park career, he became the CEO at BC Housing and later the CEO of Mountain Equipment Co-op. Most recently he led the David Suzuki Foundation through a decade of work on climate change, marine and terrestrial conservation and public education.

Yaprak Baltacioglu — responsible for providing expertise on public sector governance and decision making.

Yaprak Baltacioglu is an accomplished public sector leader with over 25 years of progressive federal government experience shaping strategic policy, overseeing programs, contributing on many senior committees and impacting government affairs at the highest levels of decision making. Ms. Baltacioglu has served as the trusted advisor to four prime ministers and numerous ministers, Cabinets and departmental officials on programs, issues, legislation and policy in areas including the economy, treasury, transportation, infrastructure, security, agriculture, healthcare and the environment. She is an expert in legislative/regulatory issues, policy development, international/government relations and the workings of government, including its principles for sound governance and government-wide policy.

Christina Cameron, Ph. D. — responsible for providing expertise on heritage conservation.

Dr. Christina Cameron holds the Canada Research Chair in Built Heritage at the Université of Montréal where she directs a research program on heritage conservation in the School of Architecture. She previously served as a heritage executive with Parks Canada for more than thirty-five years providing national direction for Canada's historic places with a focus on heritage conservation and education. She has written extensively since the 1970s on Canadian architecture, heritage management and world heritage issues. She has been actively involved in UNESCO's World Heritage Convention as Head of the Canadian delegation (1990–2008) and as Chairperson (1990, 2008).

Dr. Elizabeth Halpenny — responsible for providing expertise on sustainable tourism, recreation and protected areas management.

Dr. Elizabeth Halpenny has a Ph.D. in Recreation and Leisure Studies from the University of Waterloo (2006), a Master's in Environmental Studies from York University (2000) and a Bachelor of Arts in Geography from Wilfrid Laurier University (1992). Prior to her work as an academic, Dr. Halpenny worked with an international NGO, the International Ecotourism Society (2000–2005) as Research and Workshop Coordinator. Dr. Halpenny conducts research in the areas of tourism, marketing, environmental psychology and protected areas management. Some of her current research projects include examining the use, acceptance and impact of mobile digital technologies among tourists (i.e. festival patrons and protected area visitors); investigating the impact of world heritage designation and other park-related brands on travel decision making; and, exploring individuals' attitudes towards and stewardship of natural areas.

Steven Nitah — responsible for providing expertise related to Indigenous peoples, reconciliation and protected areas.