Audit of Occupational Health and Safety

Office of Internal Audit and Evaluation

Report submitted to the Parks Canada Audit Committee: October 24, 2019

Approved by the Agency PCEO: August 25, 2022

Her Majesty the Queen of Canada, represented by

The President & Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2022

CAT NO R62-561/2019E-PDF

ISBN 978-0-660-33115-7

List of Acronyms

ACM: Asbestos Containing Materials

AEM: Asset and Environment Management

CEO: Chief Executive Officer

CHRO: Chief Human Resources Officer

CLC: Canada Labour Code

COHSR: Canadian Occupational Health and Safety Regulations

CSR: Client Service Relationships

EAHOR: Employer’s Annual Hazardous Occurrence Report

ESDC: Employment and Social Development Canada

HOIR: Hazardous Occurrence Investigation Report

HPP: Hazard Prevention Program

HRD: Human Resources Directorate

HVAC: Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning

OHM: Occupation Health Monitoring

OHS: Occupational Health and Safety

NOHSPC: National Occupational Health and Safety Policy Committee

NVP: National Volunteer Program

OIAE: Office of Internal Audit and Evaluation

PCA: Parks Canada Agency

PPE: Personal Protective Equipment

PSPC: Public Services and Procurement Canada

SWP: Safe Work Practice

TB: Treasury Board

TSA: Task Safety Analysis

WHMIS: Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System

VP: Vice-President

| Executive management (PCX levels) |

|

| Senior management |

|

| Management |

|

| Supervisor |

1 Executive summary

Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) is a multi-faceted field concerned with the mental and physical health and safety of people in their workplaces. As a federal government employer, Parks Canada Agency (PCA or the Agency) must comply with the federal OHS legislation that is set out in the Canada Labour Code (CLC) Part II and the associated regulations. As a separate employer the Agency is not required to adhere to the Treasury Board (TB) OHS policy or the National Joint Council OHS directive. That said, the Agency used these policy documents as guides in the development of the 2001 OHS Policy.

The Agency recognizes that its greatest asset is its employees and commits to providing a safe and healthy workplace by preventing accidents, illnesses and eliminating and/or reducing occupational risks. The consequences of non-compliance with the OHS legislation can be severe, namely harm to employees, and can including considerable fines and/or imprisonment for those that are accountable, which underscores the importance that the federal government places on protecting the health and safety of employees at work, as well as the need for OHS-related accountabilities to be understood and carried out within the Agency.

The mandate of PCA is to protect and present nationally significant examples of Canada's natural and cultural heritage. This involves delivering a multitude of programs across the country, in a wide range of indoor and outdoor environments and landscapes, four seasons of the year. The varied work performed by Agency staff ranges from office work, to higher risk activities such as operating heavy equipment to provide highway services, performing search and rescue activities, using large power tools in a workshop, immobilizing wildlife, fighting wildfires or providing avalanche control and law enforcement services. Much of the work is seasonal and staff numbers in 2018 increased from approximately 4600 in the off-season to 8700 during the operational season. Many new or temporary employees can be inexperienced and may not be knowledgeable of the health and safety requirements of Parks Canada workplaces. The varied types and complexity of work performed by Parks Canada employees, combined with the seasonal nature of much of the work and workforce, positions OHS as an Agency priority.

The OHS Program at Parks Canada spans the entire organization and includes every employee including the Chief Executive Officer's (CEO) Office, the seven directorates, and the 33 field unitsFootnote i in all thirteen provinces and territories. The Chief Human Resources Officer (CHRO) within the Human Resources Directorate is the corporate functional lead for the Agency's OHS Program. Executives and senior management are responsible to ensure implementation of the Program within their areas of responsibility. While all employees and persons granted access to our workplaces are responsible to apply the Program in accordance with the legislation and policies in their day to day activities.

The purpose of this audit was to provide assurance that the current management control framework helps ensure compliance with applicable OHS-related laws, regulations and Agency policies. The audit criteria and the specific components of the OHS Program assessed were selected using a risk-based approach. The scope of the project focused on the management of the OHS Program between October 2016 and October 2018.

Key findings

Many required elements of the OHS Program were in place, including: an approved OHS policy; a defined policy framework; approved standards for several specific components of the Program with supporting tools to help business units implement the requirements; documented roles and responsibilities; and mandatory basic training and tailored training courses. Internal communication mechanisms were also in place to share information internally and for some external stakeholdersFootnote ii. However, the OHS Program requires significant investment in improving the implementation in several areas to ensure the Agency complies with federal legislation and policies, and ultimately protects its employees in the workplace. These areas include:

- renewing organization-wide commitment to OHS to complete the implementation of the program (Section 5.1 Governance);

- completing and updating standards identified in the OHS Policy Framework and supporting toolkit (Section 5.1 Governance);

- ensuring executive and senior management understand their OHS-related responsibilities and accountabilities and carry them out (Section 5.1 Governance);

- improving the rigour of work site inspections and preventive activities (Section 5.3 Hazard Prevention Program);

- making significant improvements to OHS record keeping practices (Section 5.6 Quality Information); and

- developing and implementing monitoring and reporting activities (Section 5.7 Monitoring, Reporting, and Program Evaluation).

Recommendations

There are five recommendations:

- OHS-specific priorities should be integrated into the Agency's annual Departmental Plan as identified in the Agency's OHS Policy;

- Strengthen the Agency's OHS Policy Framework by:

- Updating the OHS Policy to reflect the current organizational structure;

- Prioritizing the development and revisions to standards and tools to complete the implementation of the Agency's OHS Policy Framework; and

- Communicating the changes to this policy, related standards and tools so that accountabilities, roles and responsibilities are clearly understood by management and employees across the Agency.

- Strengthen the hazard prevention program by ensuring that:

- Hazard assessments for new and non-routine work-related activities are conducted and documented prior to the commencement of work;

- Work place committee members are appropriately trained and hold a diverse mix of knowledge related to the workplaces that allow for rigorous monthly workplace inspections and any outstanding issues are documented and tracked to closure.

- Establish and communicate clear information management standards specific to the OHS Program specifying collection, retention and accessibility requirements. This information includes training records and health assessments; and

- Strengthen monitoring and reporting of the OHS Program at both the national and business unit levels to demonstrate the performance of the Program and progress of its implementation, including identifying key performance indicators and report regularly on the successful completion rate of mandatory OHS-related training.

2 Introduction

Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) is a multi-faceted field concerned with the mental and physical health and safety of people in their workplaces. Across Canada there are fourteen jurisdictions, one federal, ten provincial, and three territorial; each has its own OHS legislation. As a federal government employer, Parks Canada Agency (PCA or the Agency) must comply with the federal OHS legislation which includes the Canada Labour Code (CLC) Part II, the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (COHSR), the Maritime Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (MOHSR), and the Policy Committees, Workplace Committees and Health and Safety Representatives Regulations.

The CLC Part II, Occupational Health and Safety outlines the duties of both the employer and the employees. Employers must protect the health and safety of employees by identifying, assessing and mitigating hazards in the workplace. Employers must also establish a policy committee and local workplace committees or representatives to help deal with OHS matters.

The mandate of PCA is to protect and present nationally significant examples of Canada's natural and cultural heritage. This involves delivering a multitude of programs and projects across the country, in a wide range of indoor and outdoor environments and landscapes, four seasons of the year. The varied work performed by Agency staff ranges from office work, to higher risk activities such as operating heavy equipment to provide highway services, performing search and rescue activities, using large power tools in a workshop, immobilizing wildlife, fighting wildfires or providing avalanche control and law enforcement services. Much of the work is seasonal and staff numbers in 2018 increased from about 4600 in the off-season to about 8700 during the operational season. Many Parks Canada staff serve in seasonal roles and have served for many years. Others function in more temporary capacities, such as casual employees and youth hired through federal youth employment programs. Many new or temporary employees can be inexperienced and may not be knowledgeable of the health and safety requirements of Parks Canada workplaces. The variety, complexity and risk levels of the work performed by Parks Canada employees, combined with the seasonal nature of much of the work and workforce, positions occupational health and safety as an Agency priority.

When compared to 180 other federal government employers, Parks Canada ranked ninth on a list of 18 organizations identified by Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) in 2016 as very high riskFootnote iii from an OHS perspective.

3 Audit purpose and scope

The 2016-2017 to 2018-2019 Parks Canada Internal Audit Plan included the audit of the OHS Program. The purpose of the audit was to provide assurance that the management control framework in place ensures compliance with applicable OHS-related laws, regulations, and Agency policies.

The audit criteria were based on the risks identified in the four elements of the Program:

- Establishment of OHS governance;

- Completion of hazard identification and assessments;

- Program implementation and incident management; and

- Monitoring, reporting and program evaluation.

The audit considered the responsibilities of both the National Program Office and business units and selected specific components of the OHS Program for review using a risk-based approach. The scope of the project focused on the management of the Program between October 2016 and October 2018. When necessary for analysis purposes, the audit team used program data as far back as January 2014.

The audit did not examine the Agency's disability management and mental health and wellness programs or ergonomic assessments. Also, the audit did not undertake any technical or specialized assessments of work sites.

More information about the audit criteria and methodology can be found in Appendix A.

4 Audit opinion

The Agency established many key elements of the OHS Program including: a governance structure including OHS committees; an OHS policy framework supported by several standards and defined roles and responsibilities for key stakeholders; and training courses. Tools were created by the National OHS Program team to help business units implement the hazard prevention program in their workplace, including a task safety analysis process and generic safe work practices. Processes are also defined to guide business units in the event that a hazardous occurrence happens. While an OHS policy framework has been established, a number of items in the policy framework need to be reviewed and updated, and others still need to be developed. Internal communication mechanisms in place need to be strengthened to improve their effectiveness. Gaps in the Agency's processes to manage its OHS-related obligations with respect to certain external stakeholders who are granted access to our workplaces also require attention.

The implementation of the Program also requires investment to improve several areas including record keeping practices, training, hazard assessments and some specific control mechanisms. To better understand the level of Program implementation across the organization, and improve its effectiveness and compliance, the Agency must improve how it monitors and reports on the OHS Program.

A successful implementation of the Program will require an organizational culture where OHS is ingrained in the way all employees conduct their work and OHS-related decisions begin and end the work day. Executive management will need to continue their recent improvements to setting the right leadership tone and ensure a strong OHS culture is established at all levels of the organization.

5 Observations and recommendations

The various areas examined by the audit presented some common issues with similar underlying causes. In these cases, the audit made recommendations at the systemic level to target these gaps.

5.1 Governance

Criteria:

- Demonstrate commitment to health and safety by setting a positive tone at the top;

- Roles, responsibilities and accountabilities, and a policy framework are established for the execution of the health and safety program;

- Oversight of the development and performance of the health and safety program is established and operating; and

- Mechanisms are established to hold individuals accountable for their health and safety responsibilities through performance measures, and corrective actions.

Program Governance

Appropriate governance of an OHS program contributes to program development, implementation and maintenance. Governance includes setting the tone, or positive OHS culture, as well as establishing and communicating objectives and priorities for the program. This also includes establishing and resourcing an organizational structure and defining and communicating responsibilities and accountabilities for the program. Governance should also provide oversight to determine if the program is meeting its objectives and legal obligations, or needs to change course to do so.

Organizational Commitment

All Agency employees have a duty to keep the workplace safe. Those individuals in key leadership positions play an important role in developing and maintaining a healthy and safe work cultureFootnote iv. Organizations are led from the top by executive management who communicate and demonstrate their business ethics and philosophies to employees and stakeholders by their words and actions. An organization's leadership at all levels promotes the importance of health and safety at work to help establish a cultural behaviour where all Agency employees prioritize their health and safety and perform their work in a safe manner.

At the Agency, all senior managers are expected to set the right leadership and culture by communicating their ongoing commitment to OHS, and demonstrating visible and consistent support for OHS in decision making, both at the executive and the operational levelsFootnote v.

The PCA OHS Policy identifies that the CEO is responsible for integrating OHS into the Agency's annual departmental planFootnote vi. The departmental plans covering the period of the audit did not include references to health and safety as it relates to employees and the workplace.

Three main governance committees at Parks Canada are attended by executive management. Between 2016 and 2017 OHS-related items were discussed twice. In 2018, seven OHS-related items were presented. The increase corresponds with the Agency's decision to appoint the Senior VP of Operations as the OHS and Workplace Wellness Champion in the same year. The Agency-wide communications were focussed on mental health and workplace wellness, which are part of the federal government-wide corporate commitments for executives. Communication from executive management has improved to better convey the importance of a healthy and safe workplace, including the promotion of existing tools, desired behaviours and attitudes.

Executive managers of business units are expected to contribute to the positive OHS culture within their organizations. The OHS leadership at the business unit level at some sites was favorably perceived by interviewees who noted a positive improvement in the past two years. The employees believed OHS to be a sincere concern and a priority for their senior management, and indicated that it was a common topic at management meetings. They provided examples where management delayed work until health and safety requirements were met, or outsourced work that was deemed too dangerous.

The strength of the OHS culture and the degree of program implementation varied between, and within, business units that were visited. High-risk functions within the AgencyFootnote vii had established stronger OHS cultures and had higher levels of implementation and compliance than the functions within the organization that performed lower risk activities. In the business units where the OHS Program was made a priority, senior management:

- Was highly involved in OHS communications and activities such as safety days and orientation;

- Ensured that ideas and concerns were freely raised and acted on;

- Encouraged employee participation in the Program;

- Was clear on expected behaviors; and

- Granted additional resources to OHS.

Strong OHS-related leadership at workplaces will help establish a culture where management and employees strive to improve performance and compliance with OHS requirements. Workplaces with less engaged leadership may have a weaker OHS-related culture resulting in higher OHS-related risks to employees. With a supportive management cadre and a strong culture, employees will be more inclined to exercise their OHS responsibilities and rights.

This report presents some systemic issues where there are opportunities to improve the implementation of the OHS program at all levels of the organization. This will require leadership by management and employees. By integrating OHS into the annual Departmental Plan this would set a positive OHS tone and drive actions to strengthen the program and reinforce the Agency's OHS Policy opening statement that identifies that "employees are the Agency's greatest asset" and that their health and safety is the top priority and fundamental to enabling the success of the Agency.

| Recommendation 1: | |

|---|---|

| The CEO should strengthen the Agency's commitment to a positive OHS culture by including OHS-related priorities in the annual Departmental Plan as required by the Agency's OHS Policy. | |

| Management Response: The Agency is committed to the health and safety of its employees. The Agency agrees that a positive OHS culture is a priority and will ensure it is communicated and implemented through its business planning process, Executive Performance Management Agreements and the 2020-21 Departmental Plan. The OHS policy refresh will include an assessment of the best means of ensuring a positive OHS for 2021/22 and beyond. |

Completed October 2020 |

OHS Program Structure

The Agency works under a decentralized model with a corporate service delivery model led from the National Office and operational business units spread out across Canada. The OHS Program is also based on this model with corporate functional leadership provided by the CHRO within the Human Resources Directorate (HRD) while program implementation occurs at the business unit level across the Agency.

The National OHS Program team, within the HRD, consists of a manager and four employees. This team leads the development of program policies, standards, tools, and training, and provides program oversight. Also within the HRD, a Client Services Relationships (CSR) group includes three OHS Advisors who are the link between the National OHS Program team and the business units. They provide OHS advice and guidance to managers and employees, case management assistance, training delivery, and community engagement. The information they gather through their client interactions is shared with the National OHS Program team to help shape the Program.

Managers are responsible and accountable for people management within their business units, including implementation of the OHS Program for their employees. During the operational season, approximately 80% of the Agency's total workforce (≈7000 employees) report to the field units within the Operations Directorate, working in national parks, the national urban park, national historic sites, marine conservation areas and administration offices that are distributed across the country. Each field unit is managed by a Field Unit Superintendent that reports through an executive director to the Senior Vice-President of Operations. Currently 10 of the Agency's 33 field units have identified a resource with some OHS program responsibilities ranging from a partial to full-time dedicated resource. In total, the combined capacity of OHS support in the business units is approximately equivalent to six full-time employees.

The Agency has determined that the current level of OHS resourcing in the Agency is not sufficient for development, support and implementation of an effective OHS program in the Agency and is seeking an increase in OHS funding for additional positions.

OHS committees and representatives, required by the CLC, form a key part of the governance structure for the OHS Program at the Agency. The National Occupational Health and Safety Policy Committee (NOHSPC) focusses on health and safety matters that affect the Agency on a national level, while workplace committees, or OHS representatives at sites with less than 20 staff, are established to address health and safety matters within individual workplaces. The duties and operating requirements of the policy committee, workplace committees and OHS representatives are set out in the legislation, and in the terms of reference for the committees in the AgencyFootnote viii.

The OHS Program structure aligns with the Agency's organizational model and also meets the requirements set out in the CLC for OHS committees. However, the number and capacity of OHS-related positions to support the Program differs between business units which could require a review of how the Program is resourced.

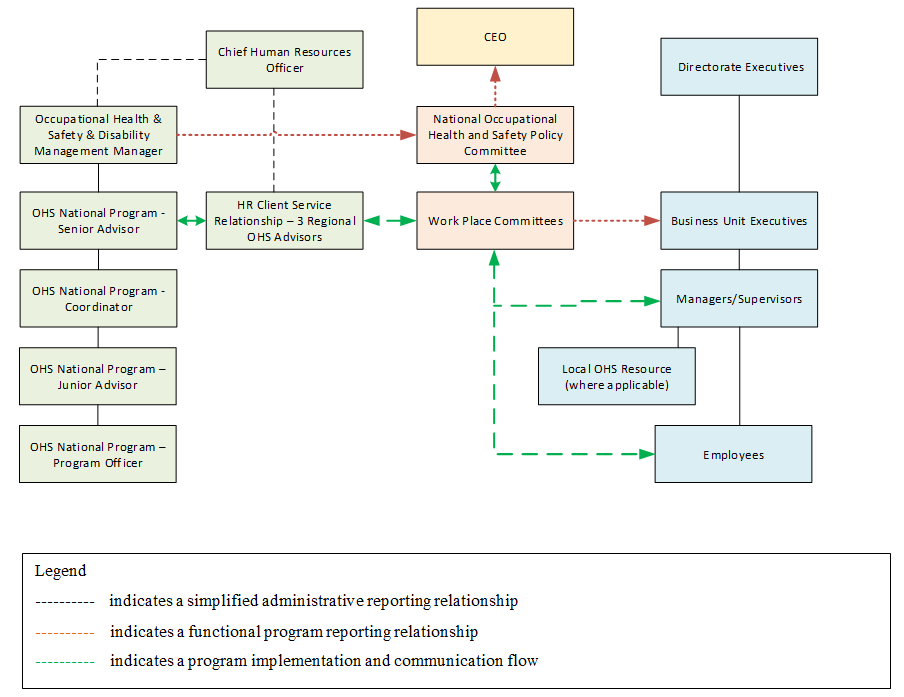

Figure 1 — Occupation health and safety program structure

Figure 1 — Occupation health and safety program structure — Text description

Figure 1 depicts a simplified OHS Program structure in which the OHS and Disability Management Manager and their four employees report to the Chief Human Resources Officer. This manager has a functional program reporting relationship with the National Health and Safety Policy Committee that report to the CEO. The senior advisor for the national OHS program works in collaboration with three regional OHS advisors to provide the HR Client Services. They support work place committees that perform functional work within each of the directorates that provide the flow for the communication and program implementation. This is shared with managers, supervisors, employees and, when applicable, local OHS committees.

Accountabilities and Responsibilities

OHS legislation and the Agency's OHS program are based on the fundamental premise that workplace health and safety is a shared responsibility. Employers, employees and OHS committees all have important roles to play to protect the health and safety of people at work. The CLC and relevant regulations set out detailed duties for employers, employees, and workplace committees. The CLC alone contains 52 specific OHS-related duties of an employer that are relevant to Parks Canada, and 10 for employees.

Understanding accountabilities for OHS is critical as the consequences of non-compliance with the legislation can be severe. Under Part II of the CLC, anyone found in contravention of a provision is guilty of an offence and is liable for fines of up to $1,000,000, and could face up to two years imprisonment. Additionally, an organizationFootnote ix can be held accountable for criminally negligent acts/omissions.

In accordance with the PCA OHS Policy, issued in 2005 under the authority of the CEO, the CHRO is functionally accountable for the OHS Program at the Agency and Executives are accountable to implement the Program within their business units. Responsibilities are delegated downward to managers who are closer to frontline employees and their workplaces, and have the knowledge to make better informed decisions for their people and places. Under the policy, employees are responsible to comply with all aspects of the program: follow prescribed procedures, use proper materials and report potential and actual hazardous occurrences.

Fundamental OHS responsibilities are included in the Agency's OHS training courses that are mandatory for all employees, managers, supervisors and OHS committee members. Detailed accountabilities and responsibilities for OHS are defined in three main documentsFootnote x as well as in several specific directives, standards and guidance tools. A review of these documents revealed that their content is not always clear as they contain contradictions and the Policy itself assigns responsibilities to positions that no longer exist in the organization, such as the Regional Health and Safety Coordinators. This lack of clarity increases the likelihood that program responsibilities are not well understood which could cause implementation issues.

Employees and supervisors at the business units have a basic understanding of the OHS Program requirements and their roles and responsibilities. Employees understood that they are expected to undertake training and apply that knowledge, work safely and not endanger themselves and/or others, and report concerns and incidents to their supervisors. Supervisors understood their responsibilities to inform and train employees, ensure employees use the correct tools and protective equipment and work safely, and investigate complaints and implement corrective actions.

However, supervisors and managers at the business units did not have a thorough understanding of the breadth and depth of their program implementation responsibilities. Further they were not aware of their accountabilities and potential liabilities under the CLC and Criminal Code. This lack of understanding undermines OHS compliance and consistent program implementation across the Agency. This issue will be addressed through recommendation 2 presented below.

OHS Committee Operations and Performance

The National OHS Program team provides support and secretarial services to the NOHSPC, including the preparation of program proposals, and draft meeting agendas and meeting minutes. NOHSPC meeting minutes provided evidence that the committee is meeting quarterly as required by its Terms of Reference, and is complying with the legislated administrative requirements for committees, including committee composition, quorum, approved and available meeting minutes. The members also participate in the development of health and safety policies and programs, including the Agency's hazard prevention program, discuss OHS issues and make health and safety recommendations to the CEO. This duty is achieved by reviewing and commenting on documents and presentations tabled to the committee by the National OHS Program team for review and discussion. The NOHSPC, however, is less active in executing its mandated monitoring and reporting responsibilities. This area for improvement is discussed further in section 5.7 of this report.

In 2017, the Agency had established 79 workplace committees across the country to represent all employees. While all the workplace committees reviewed at the business units visited during the audit were functioning and were mostly compliant with requirements, some were more effective than others. Effective committees had members representing a broad base of work functions, met more frequently, had a more rigorous workplace inspection program, participated directly in conducting hazardous occurrence investigations, and were active in documenting and addressing identified OHS issues and complaints. Conversely, other committees had opportunities to improve by:

- Updating out of date terms of reference;

- Meeting at least nine times a year per the legislative requirementFootnote xi;

- Performing monthly inspections at each workplace as required;

- Strengthening accuracy of figures reported annually by committees that included the number of accidents, injuries and health hazards; and

- Strengthening poor record keeping practices that were affecting quality of reports (e.g. number of injuries, inspections).

The Agency established the required NOHSPC and workplace committees, but there are opportunities to improve how these committees carry out their responsibilities that will help strengthen the governance of the OHS Program. This will be addressed through recommendation 2 below.

Policy Framework

A complete and aligned policy framework is imperative in order for the Agency to meet its mandated requirements, and to communicate program expectations to stakeholders. The Agency's OHS-related policies, standards and guidelines must align with the CLC and the related regulations, and the agency's operational requirements.

The Agency's OHS policy framework was designed under the leadership of the CHRO and the National OHS Program teamFootnote xii. In addition, the National OHS Program team developed several standards, guidelines, tools, training and templates to further help managers implement the Program in their respective functions. The framework is anchored by the 2005 PCA OHS Policy which provides the Agency's general policy concerning the health and safety of employees at work as required by the CLC. This overarching policy is supported by a Hazard Prevention Directive and several detailed standards and guides. However, some standards have yet to be developed including: hazardous substances, tools and machinery, and materials handling (see Appendix B). Although legislative requirements are outlined in the CLC and regulations, without Agency-specific standards, roles and responsibilities may not be clearly assigned, nor will any specific requirements for Agency workplaces be outlined.

The CLC, Part II requires employers to ensure that all buildings and structures meet prescribed standards. These employer duties are included in the PCA OHS policy. Within the Agency, the National Asset and Environment Management (AEM) team is the corporate functional lead for asset management including compliance with building codes. They provide standards, guidelines and advice to business units who maintain the assets and execute equipment tests. Asset maintenance and testing are essential elements of OHS, but most of these standards are not included in the Agency's broader OHS policy framework. This situation creates uncertainty related to the accountability for compliance with prescribed standards. The Agency should clearly define the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of the various functions involved in the health and safety of employees without being formally integrated into the OHS management framework such as Asset and Environment Management, Security and Project Delivery.

The 2015 Federal Infrastructure Investment Program led to an increase in the quantity and scale of construction projects and raised management concerns as to whether the Agency has provided adequate direction on its OHS expectations related to construction projects. The OHS policy framework and supporting tools are largely silent on construction worksite health and safety. The Agency's current process and tools for construction project contracts may need to be enhanced to better address OHS requirements. Currently, a multi-functional working group has been established and a resource was assigned to draft the Construction Safety Standard and Guide to address the gaps.

The Agency's conservation mandate may conflict with legal obligations to comply with current building codes and standards while trying to respect commemorative integrity. Professionals such as engineers and architects may recommend repairs and/or renovations to sites or structures with natural or cultural heritage importance. In some cases, these proposals, which are aligned with current codes and standards, may compromise the heritage value and character-defining elements of the site or structure if implemented. An example of this would be the lack of guard-rails along a historic canal. GuidelinesFootnote xiii are in place to help determine the most appropriate solution to health, safety and security requirements with the least impact on the character-defining elements and overall heritage value of the historic place. Although field superintendents are accountable for decisions made in their area of responsibility, the Agency should clarify the liability of its professionals when their work may not meet the standards of their professional designation in order to preserve commemorative integrity.

The Agency's employees often have irregular working arrangements where they physically report to a different business unit than their functional management, either temporarily or permanently. For example: a fire management officer temporarily joining a wildfire crew in another business unit as part of an incident management team, or an IT officer working in a satellite office to provide support in that region. These working arrangements can make the requirements for identification, reporting and communication of potential or actual hazards, and hazardous occurrences confusing for both management and employees. OHS accountabilities are aligned to workplaces and not to functional reporting lines and the Agency's policy framework is written with the underlying assumption that management and the employee work in the same business unit. They do not account for employees working under irregular working arrangements. The current OHS policy framework does not provide enough clarity to ensure proper identification, reporting or communication of issues between functional management and the management accountable under OHS for employees working in these alternate workplaces.

The Agency's OHS policy framework is not implemented completely. Without clear policy guidance that defines accountabilities, roles and responsibilities, employees may be more vulnerable to occupational hazards. Completing the implementation of the framework and addressing identified gaps will help provide the direction and tools that management and employees require to implement the Program.

| Recommendation 2: | |

|---|---|

To complete the implementation of the Agency's OHS Policy framework the CHRO must:

|

|

|

Management Response:

|

Targeted Completion Date: March 2024 |

Internal Communications

Communication focuses on the transmission and understanding of messages throughout an organization. Effective communication involves complete, accurate and timely messages that help to align expectations and behaviours towards the achievement of objectives.

The OHS Program has a broad scope and both the legal and Agency requirements are numerous and detailed. The National OHS Program team relies on various methods to communicate OHS program information to managers and employees, including OHS-related: policies and guidelines available on the Agency's Intranet, mandatory training, newsletters and emails and bulletin boards at workplaces. OHS-related information is also communicated through OHS teleconferences, service calls to the CSR group and the organization's chain of command.

These communication mechanisms are limited at reaching employees throughout the organization because:

- A significant amount of OHS information shared on the Intranet is outdated;

- Not all employees have routine access to a computer; and

- OHS-related information communicated to management and intended for all employees is not consistently communicated throughout the organization.

The Agency is required to post a copy of the CLC, the Agency's OHS Policy, workplace committee meeting minutes in a prominent place accessible to every employee in each workplace for one month, and names/contact information for committee members. Less than half of the workplace bulletin boards examined during the audit complied with these posting requirements.

If OHS-related information is not shared and understood throughout the Agency, the Program will not be implemented effectively. The implementation of the Agency's OHS Policy Framework can be improved by strengthening internal communication.

5.2 Hazard prevention program

Criteria:

- Occupational health and safety risks are identified, assessed and mitigated at all work sites across the Agency; and

- Changes that could significantly impact health and safety are identified and assessed.

Hazard Identification and Assessment

Hazards, or a potential for harm, exist in every workplace. By systematically identifying hazards, the Agency will be better prepared to mitigate and reduce the risk of accidents, injuries, property damage and downtime.

OHS legislation requires that all federal employers develop, implement and monitor a hazard prevention program (HPP). The program must include: an implementation plan, a hazard identification and assessment methodology, a hazard identification and assessment, preventive measures, employee education and program reviews.

The Agency's HPP is defined in the 2013 Hazard Prevention Directive, the 2013 Hazard Prevention Standard and a suite of supporting tools. These policies and tools are featured in the Agency's mandatory OHS training. They assign responsibilities to the National OHS Program team to govern the HPP and entrust the business units' senior managers with implementation in their area of responsibility.

The Agency's hazard identification and assessment methodology for routine and non-routine work is called the Task Safety Analysis (TSA) which consists of:

- identifying tasks or work conditions with a health and safety risk;

- identifying all hazards associated with these tasks or work conditions along with corresponding preventive measures; and

- documenting a safe work practice (SWP) for each critical taskFootnote xiv. The SWPs contain information on hazards and the control measures that need to be taken when performing the task.

The Agency developed a National Inventory of Hazards and a National Inventory of Generic Safe Work Practices to assist managers in implementing the TSA process within workplaces. Workplaces may adopt or adapt generic SWPs if these documents accurately identify and address the hazards and risks associated with their critical tasks; if not, they must create local SWPs.

The senior manager of each business unit must make sure that the TSA process is implemented within their workplaces and approve that each SWP to be implemented is appropriate for the workplace.

The TSA process was not implemented at all the business units visited during the audit. Four business units had not conducted any TSAs within the time period covered by the audit and had few, or no local SWPs. Their process to address non-routine work took the form of a discussion between frontline supervisors and their staff prior to undertaking the work. This hazard assessment process was not documented. The other two business units conducted TSAs for their workplaces on an ongoing basis, created site specific SWPs and conducted and documented hazard assessments for non-routine work. OHS-related leadership and culture were stronger in these two business units.

The absence of systematic hazard identification, assessment and mitigation may expose employees to hazardous occurrences with grave consequences.

Workplace Inspections

Workplace inspections are an important component of an organization's HPP. They help the organization identify and assess hazards present in the workplace and facilitate the implementation of preventive measures. Workplace committees are required under legislation to inspect all or part of the workplace each month, so that every part of the workplace is inspected at least once each year. Inspections must be documented, and issues must be communicated to responsible managers in a timely fashion and resolved.

All seven workplace committees operating in the sites visited during the audit performed and documented workplace inspections. In 2017, six of the seven committees performed inspections in all of their defined workplace areas during the year as required; one had not. Only two of the seven committees met the requirement for monthly inspections. The frequency of inspections ranged from one a year to the required twelve monthly inspections.

Committee members communicated inspection deficiencies and other issues to the responsible managers in a timely fashion, but some committee minutes did not demonstrate how outstanding actions were resolved. For example, meeting minutes for three committees simply noted that the inspection of a particular workplace was discussed at the meeting, and nothing more. More rigorous committees tracked outstanding actions in their meeting minutes until resolved.

As a part of the audit field work, walkthroughs were conducted at work sites in which these seven committees operate and deficiencies that were observed included:

- Materials for disposal not stored properly or disposed of in timely fashion;

- Unlabeled and expired hazardous materials, out of date safety data sheets;

- Propane tanks/cylinders not stored and secured properly;

- Overhead materials not stored or secured properly;

- Tripping hazards, obstructed emergency exits;

- Lack of lock/tag out systems for tools/equipment;

- Unlabeled electrical panels, uncapped wires;

- Lift devices and other material handling devices not inspected in timely manner;

- Lack of hand rails and guard rails;

- Lack of signage (asbestos, low overhead, etc.);

- Workshop ventilation systems in need of maintenance/repairs; and

- Inconsistent processes and record keeping for fleet preventive maintenance and manufacturer recalls.

To improve the effectiveness of employer's OHS programs, the CLC requires OHS committee members to be trained on the legislated roles, responsibilities, and operational requirements of OHS committees. The Agency's mandatory OHS training for committee members helps to meet these specified training requirements and provides additional guidance to help committees function effectively. The Agency also offers optional training on workplace inspections to help workplace committee members carry out meaningful inspections. Of the 58 members in these seven workplace committees, 38 employees had completed the Agency's mandatory OHS training for committee members, and only 18 had received the optional training on workplace inspections.

Without properly trained committee members and a rigorous inspection program, there is an increased risk that hazards in the workplace are not identified in a timely manner and employees are exposed to unidentified and unmitigated hazards. This issue will be addressed through recommendation 4.

Maintaining the Hazard Prevention Program

Hazards can change and new ones can be introduced into a workplace as the environment and work processes change. The Agency needs to keep abreast of these changes, assess their impact and modify their HPP as needed, in order to best protect the health and safety of its employees. This is not only a good practice but a legislated requirement. Under the COHSR, the Agency must evaluate the effectiveness of the HPP and make any necessary improvements at least every three years, whenever there is a change in conditions in respect of the hazards, and whenever new hazard information becomes available.

During site visits, various activities to update the HPP were observed. For example: business units had engaged a manufacturer to train employees on safe use of new machinery, and a number of local SWPs were created following the introduction of new tasks, such as the use of drones. However, as previously identified, gaps exist in the conduct and documentation of hazard assessments and TSAs, increasing the risk that changes or new hazards that arise in the workplace may not be adequately assessed and mitigated.

The Agency's Hazard Prevention Standard requires that all hazards be identified and incidents reported to the workplace committee. Workplace committees then report annually to the Labour Program on the number of identified, resolved and unresolved hazards. All seven committees in the sample submitted their annual reports to the Labour Program over the audit period. However, two committees did not identify any hazards in their annual reports which may point to a reporting weakness or a committee training issue as both committees found deficiencies during monthly inspections and discussed Hazardous Occurrence and Incident Reports regularly at meetings.

At the national level, the National OHS Program team stays aware of legislative changes by participating in a community of practice and through direct communications with TB and other relevant departments such as Health Canada and ESDC. In the period covered by the audit, new OHS-related policies have come into effect and some of the existing policies were modified to reflect government-wide changes.

New information with respect to hazards is also received from manufacturers and service providers, notably in the case of safety recalls. The Agency uses the PCA OHS community teleconferences and/or direct emails to executive management and functional leads to disseminate such information across the Agency. There is no evidence, however, that required changes are monitored for implementation. For example, recalls regarding vehicles and fire alarms were communicated, but confirmation that appropriate remedial actions were taken was not required by the National OHS Program team or at the business unit level.

The prevention of hazards is a significant component of the OHS Program. Work was undertaken to identify hazards, and create safe work practices, but further efforts are required to strengthen hazard assessments at the local level, workplace committee activities and inspections and following through to confirm any issues that require actions are carried out.

| Recommendation 3: | |

|---|---|

|

The Senior VP Operations, VP Protected Areas and Establishment, VP Strategic Policy and Investment, VP Indigenous Affairs and Cultural Heritage, VP External Relations & Visitor Experience and the Chief Financial Officer with the support of the CHRO should strengthen the hazard prevention program by ensuring that:

|

|

| Management Response:

1. Management agrees to establishing a plan to implement local HPP, which includes: regular hazard assessments, tailgate meetings, planning, training, supervision, personal protective equipment (PPE) and mitigating measures for ongoing tasks and prior to undertaking new or non-routine tasks.

2. Management agrees that reviewing, providing guidance, training and tools to business and field units on the requirement associated with the HPP process is required.

3. Management recognizes the investment required in the OHS program to strengthen the agency's commitment of promoting a culture of safety. |

Targeted Completion Date: March 2023 |

5.3 Training and learning

Criteria:

- Commitment exists to develop and train a competent workforce by establishing policies and practices, evaluating required competences and addressing gaps.

Employee training is used to efficiently communicate the requirements set out in the Agency's policies and procedures so staff understand what is expected and can translate these expectations into action. Training supports program effectiveness and improves the likelihood of achieving objectives. The CLC requires the Agency to provide employees with appropriate training to help ensure their health and safety at work. Employees, managers and committee members must all receive training on their rights and responsibilities under the CLC. Specialized training on specific hazards and preventive measures must also be provided when required.

OHS training requirements at the Agency align with the legislated requirements. All employees must complete mandatory OHS training prior to starting their work. Additionally, employees must receive specialized training on specific hazards and preventive measures relevant to the tasks they perform. Managers and supervisors have the delegated responsibility to make sure that their employees are adequately trained.

The mandatory OHS training consists of three online courses that cover the legislated rights and responsibilities for OHS, as well as the key OHS policies and processes at the Agency. All employees are required to complete the Level 1 training. The Level 2 course is mandatory for managers and supervisors, and the Level 3 course is mandatory for OHS committee members. All three courses must be completed before the individuals begin carrying out their respective duties and are to be retaken every 3 yearsFootnote xv.

The Agency tracks the completion of all three levels of training in a centralized database. Data analysis revealed that 71.5% of employees, 63.5% of supervisory/managerial staff, and 65.5% of workplace committee members have completed the relevant mandatory trainingFootnote xvi.

Managers and supervisors identified that the seasonality of the Agency's operations and short on-boarding periods present challenges to the delivery of training. Analysis of completion rates by employment type showed that rates are considerably lower for students (53.8%) and short term and casual employees (60.1%) than for indeterminate or returning seasonal workers (83.4%). OHS literature indicates that new and young workers are three times more likely to be injured during the first month on the job than more experienced workersFootnote xvii. Lack of experience to recognize workplace hazards coupled with low rates of training might make these employees vulnerable to occupational hazards.

The training required for specific hazards and preventive measures is identified in the Agency's SWPs and its completion is documented through SWP attestation forms and training records, such as certificates, licences, participant lists, etc. Depending on the tasks, employees may obtain hazard specific instructions through a combination of online, classroom, hands-on training and a review of SWPs.

Managers at the business unit level need to track hazard specific training in order to ensure that their employees receive the training they require. Currently, hazard specific training is not tracked in the Agency's centralized database. The responsibility for maintaining training records is not clearly defined. Consequently, training records are dispersed among Human Resource Managers, supervisors, employees, various databases, and in some instances training records could not be provided at all. Only two of the business units visited had sufficient documentation to demonstrate that training on specific hazards and preventive measures was provided as required. Without records and controls to track hazard specific training, there is an increased risk that employees will not be adequately trained to work safely and prevent illness and injury.

In December 2018, the National OHS Program team announced the launch of a new module within the Agency's centralized training database that would allow business units to use the system to track their OHS training identified in generic SWPs, additional OHS training, and manage training renewals. Use of this tool is optional but as of June 2019 five business units have started to use it. There is an opportunity for executive management to set the tone and require that the tool must be used by all business units.

Currently, the Agency is not meeting the requirements to provide general training to all employees on their responsibilities under the CLC, and specific training related to hazards in the workplace based on each individual's responsibilities and tasks. Since adequate training is fundamental to a well-functioning program, the low rates for OHS-related training at the Agency undermine the overall effectiveness of its OHS Program. This issue will be addressed through recommendation 5.

5.4 OHS program controls

Criteria:

- Health and safety control activities are deployed as set-out in the Agency's policies, directives, standards, guidelines and procedures.

Once workplace hazards have been identified and assessed, the employer must implement preventive measures. The measures employed must be based on the level of risk and the hierarchy of control working from most effective to least effective controls for hazards through their elimination, reduction, or provision of personal protection. Without appropriate controls in place there is an increased risk of a workplace incident.

Employees Working Alone

Employees at Parks Canada are sometimes required to work alone Footnote xviii in workplaces where medical or emergency assistance is not readily accessible. Managers must consider this when implementing their hazard prevention programs in accordance with the requirements set out in the COHSR and the Agency's Hazard Prevention Standard. There are six situations identified in the regulations prohibiting employees from working alone including, for example, certain types of electrical work, and working in confined spaces under specified hazardous conditions.

The Agency's OHS documentation related to working alone includes a supervisor's guide, several planning tools to identify and mitigate the risks of working alone, and several generic SWPs. A review of the toolkit determined that there are specific directions to address most of the working alone restrictions set out in the COHSR except one. The Agency's SWP for Lock-Out and Tag-Out procedure is lacking detail calling for direct supervision of work if lock-out procedures cannot be implemented. Without clear instructions, there is a risk, that legislated safety measures may not be implemented placing employees at a higher risk of illness and injury.

Typical controls used when staff must work alone, as well as for teams that work remotely, involve: planning the work so that the supervisor knows where each person or team will be working during the day; and communication check-ins with a prearranged contact using a radio or cell phone. Work planning and check-in controls range from formal to informal depending on the workplace, timing and task to be performed. Formal procedures may involve communications check-ins with a centralized 24/7 dispatch service within PCA. Other procedures may be as informal as an employee waiting at the workplace at the end of the day to make sure that all employees working remotely return.

Communication check-ins can be problematic due to areas with unreliable or non-existent radio or cell phone coverage. In these situations, check-in times may be adjusted, work may be interrupted to relocate to an area where radio or cell phone communication is possible to permit check-ins, or satellite communication devices may be used. Managers and employees indicated that they were comfortable with their procedures for working alone, and despite the different approaches in these procedures, they appear to be mostly effective.

Hazardous Substances in the Workplace

Many Agency employees are at risk of exposure to numerous and varied hazardous substancesFootnote xix due to their presence and use in our workplaces. Common examples of hazardous substances found at business units include cleaning products, gasoline, paint, propane, and asbestos.

In the interest of both safety and transparency, the Government of Canada requires departments and agencies to publish a national inventory of assets containing asbestos and their locations, and identify if asbestos management plans are in place. As of February 2019, the Agency had published 226 locations with asbestos containing materials (ACMs), of which 184 had asbestos management plans in place, 38 locations had plans in progress and 4 locations did not have plans. The Agency intends to complete management plans for all locations with ACMs.

OHS legislation around hazardous substances include requirements that address: records of hazardous substances in the workplace; storage, handling and use; warnings and labels; and employee education and training. At the Agency level, the National OHS Program team and the Environmental Management group work collaboratively to provide direction and guidance to prevent and mitigate exposures to hazardous substances in the workplace in line with the legislated requirements.

The policy and procedures for the effective management of ACMs were recently updated. Additionally, several generic SWPs are developed that provide guidance for the safe handling, storage, and use of hazardous substances in the workplace. At the time of this report an overarching standard for hazardous material was under development as part of the OHS Policy framework.

Both compliant and non-compliant practices were observed in the six business units visited related to the availability of safety data sheets, labelling and storage of hazardous substances. The National OHS Program team also defined mandatory training requirements for employees who may handle or be exposed to hazardous substances. These include specific training on the use of hazardous products, Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS) training, and, if applicable, asbestos awareness and asbestos handling training.

There was a lack of evidence that employees received the required training on hazardous substances. Specifically, training records for sample employees who may handle or be exposed to ACMs and other hazardous substances showed that less than 50% of sampled employees had completed mandatory WHMIS training, and only 26% of sampled employees had completed the mandatory on-line training on basic asbestos awarenessFootnote xx. This issue linked to record keeping practices will be addressed through recommendation 4 related to information management, and training through recommendation 5 on monitoring and reporting.

Confined Spaces

Confined spacesFootnote xxi have restricted access and entering the space may become hazardous due to its design, atmosphere, contents or any other conditions in the space. Detailed requirements for working in confined spaces are defined in Part XI of the COHSR, however the audit work only confirmed the existence of Agency policies, inventories, assessments, procedures, and instruction for confined spaces.

During the audit period a draft standard for Confined Spaces and supporting tools were being developed by the National OHS Program team in collaboration with the NOHSPC and other Agency stakeholders. This standard was approved in July 2019.

Prior to the approved standard some business units had started to implement local processes and controls for working in confined spaces. These processes will require ongoing improvement. For example, only two of the work sites visited provided inventories of their confined spaces. Although both inventories identified the hazards related to the confined workplaces, only one identified the precautions, tests and protective equipment needed to work in these spaces as required by the COHSR.

Occupational Health Monitoring

The Agency's Occupational Health Monitoring (OHM) program provides health evaluations to individuals in order to help prevent or detect work related illness, injury and disability. The OHM program involves four types of evaluations:

- Pre-placement health evaluations to determine if job candidates meet the health requirements of certain positions;

- Periodic health evaluations to determine if employees continue to meet defined health criteria;

- Non-routine Fitness to Work Evaluations to determine if an employee has been affected by a workplace hazard and/or is medically fit to perform the tasks of a specific job and, what limitations, if any, should be considered; and,

- Ergonomic assessments, which were not included in the scope of this audit.

OHM program documentation developed by the National OHS Program team sets out health protocols that list the medical examinations and tests required for various occupations, activities, and work conditions. However, the available program documentation contains inconsistent and unclear requirements, as well as contradictory responsibilities. Exampled by: one program document identifies 18 health protocols and another identifies 19 protocolsFootnote xxii; the frequency of periodic medicals differs for one of the protocols; responsibilities are defined for positions that no longer exist in the organization; and there is contradictory information for who is responsible for retaining employee records.

A contract is in place to provide the health assessments required under the Agency's OHM program and the medical service provider submits detailed monthly reports to the National OHS Program team on the services provided to employees under the contract.

OHM assessments for law enforcement employees, divers and fire fighters are systematically and independently tracked and monitored by the leads for these functions within the Agency. Business units in our sample, however, could not provide any type of independent tracking mechanism to identify required health assessments, and health assessment expiry dates for their employees. Only two business units referred to the annual recall list provided by the medical service provider as their bring-forward control to identify if employees required a periodic health evaluation in the upcoming year. The recall list is not an effective control as it is provided externally and does not reflect changes to an employee's location, position, assigned duties or related hazards that could change their health assessment requirements.

Available records provided evidence that periodic health assessments were performed in compliance with the program for some employees in our sampleFootnote xxiii, including those in higher risk functions. However, there were two cases where required pre-placement health assessments were not carried out for firefighters prior to the letter of offer being offered. The assessments were done after the employees' hire dates, which does not respect the Agency's OHM Standard.

It is clear that health evaluations are being performed, however there is an opportunity to strengthen the controls and implementation of the OHM program to demonstrate that it is being effectively implemented, and all assessments are carried out as required by business units. The issues related to record keeping practices will be addressed through recommendation 4 related to information management and the issues related to OHM requirements will be address through recommendation 2 related to the policy framework.

Preventing Violence in the Workplace

ViolenceFootnote xxiv towards employees in their workplaces can be devastating and preventing it is therefore an important component of OHS. The CLC and COHSR prescribe the steps that federal employers must take to prevent and protect against violence in the workplace.

In 2017, 13 workplace violence incidents were reported and 7 were reported in 2018. The Agency established a standard, procedures and supporting tools in 2015 that align with the legislated requirements for violence prevention in the workplace, and assign responsibilities related to this program. The key program requirements are to: document and post a workplace violence prevention policy with content prescribed in the COHSR; identify, assess and control the factors that contribute to violence in each workplace; instruct employees on these factors and controls and maintain employee records of this site specific training; document, instruct employees and execute procedures to respond to and investigate incidents; and review and update the standard, as well as the implemented preventive measures in workplaces as needed due to changes or at least every three years.

The Workplace Violence Prevention program is included in the Agency's mandatory Level 1 and 2 OHS training courses for employees and for managers and supervisors. Optional training on the subject is also available through third parties. However, despite the availability of program direction, tools and training, the program has not been fully implemented as described below.

The Agency's Violence Prevention in the Workplace Standard is to be reviewed whenever changes arise that may impact the program, or at least every three years. It has not been reviewed and updated as required. A planned review was postponed pending relevant amendments to the COHSR.

Parks Canada's Violence Prevention in the Workplace Statement is to be posted in workplace locations accessible to all employees, as required by the legislation and the Agency's procedures. It is available on the Agency's intranet, but only 60% of the workplaces visited during the audit displayed the Statement.

Two business units visited during the audit implemented controls to help prevent workplace violence after experiencing incidents in their workplaces. The other four business units had not identified factors contributing to violence in their workplaces nor implemented any control measures.

As required by the legislation, the Agency's toolkit for workplace violence prevention includes a detailed procedure for how to respond to and investigate incidents of workplace violence. Interviewees in the sampled business units were not aware of this procedure. They indicated that they would report incidents to their managers, which only partially complies with the documented and expected response procedure.

At the business unit level, there's an opportunity to improve the implementation of the workplace violence prevention program. The risk of violence in Agency workplaces is not being mitigated in a systemic manner by identifying, assessing and controlling the factors that contribute to workplace violence.

Preventive Maintenance

The Agency's infrastructure portfolio is wide-ranging and includes buildings, canals, roadways, bridges and trails. The AEM group is functionally responsible for the Agency's infrastructure which must be maintained in compliance with applicable standards, inspection and maintenance requirements prescribed by the CLC, fire, electrical, and building codes, etc. The infrastructure maintenance program is supported by the National Asset Management System that includes the inventory of assets, asset status, code requirements, maintenance and testing procedures, and work orders. For the purpose of this audit, only water, heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC), asbestos and radon testing processes were considered. The audit did not validate the completeness nor accuracy of the inventory and other information in the asset management system nor the adequacy of the testing procedures.

The National Asset Management System is being implemented in phases. The implementation of inspection planning and tracking functionality started in summer 2017. At the time of the audit, some modules were fully functional and others were only partially developed. Testing programs for water quality, HVAC and asbestos are functional in the system. The radon management module is not yet implemented.

Employees from asset management within the business units are responsible for conducting the technical inspections or preventive maintenance testing required by legislation. Testing results are kept at the business unit level. The modules in the asset management system for water quality and asbestos are used and include test results. Business units have not entered all of their HVAC inventories into the asset management system therefore the HVAC module is mainly used as a repository for code requirements and testing procedures. Although the radon module is not yet implemented in the system, information about radon and a testing guide are available on the Agency's intranet.

These types of assessments are not confirmed by the OHS workplace committees during their workplace inspections. A review of workplace committee meeting minutes from the sites visited during the audit showed that only one committee is receiving regular reports allowing members to monitor these OHS-related preventive maintenance activities.

Although testing processes are defined and an information system is being implemented to capture pertinent testing and preventive maintenance requirements and results, there are no monitoring and reporting processes in place to provide assurance to management that employees are being protected and the Agency is in compliance with the CLC requirements. This issue will be addressed through recommendation 5 related to monitoring and reporting.

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE)Footnote xxv is used to counter or diminish an exposure to hazards when these hazards cannot be reduced or eliminated in the workplace. Common examples include safety glasses, safety boots, gloves, sun screen, and ear protection. In the absence of PPE when performing some tasks employees could be exposed to illness or injury on the job.

OHS legislation requires employers to develop, implement and monitor a program for the provision of PPE in consultation with their policy committees. Employers must keep a record of all PPE provided to staff, and must perform and record acquisitions, inspections, tests, and maintenance as prescribed by the legislation. Also, employees must be instructed and trained in the use, operation and maintenance of the PPE provided. The Agency's PPE Standard aligns with these legislated requirements.

Business unit employees interviewed during the audit did not raise any concerns with respect to the provision, use, repair or replacement of PPE, and the audit team observed that PPE was available and used by employees as they performed their work. However, the records for PPE were not always available, current, or complete; some did not satisfy the minimum legal requirement to record inspections, tests and maintenance. Of note, the 'Record of PPE' template, included in the PPE toolkit to help managers implement the program, also does not capture all the mandatory information related to inspection, testing and maintenance of equipment. Further, responsibility for record keeping is unclear as the PPE standard assigns responsibility for PPE records to the "employer", while other Agency documentation indicated that PPE records are to be included in the Employee Personnel Files maintained by business unit HR managers.

The National OHS Program team, the national policy committee and workplace committees each have monitoring responsibilities related to the PPE program, as set out in the PPE Standard. There was no evidence that these monitoring responsibilities are performed. There is an opportunity for oversight activities to confirm that PPEs are provided, in working condition and effective at preventing or reducing hazards. The issue related to record keeping practices will be addressed through recommendation 4 related to information management.

Hazardous Occurrences Investigation Reporting and Recording (HOIRR)

A hazardous occurrence is an event or incident in which a personal injury, fatality or property damage has or could have occurred (near miss). Investigating hazardous occurrences and analysing the collected information could help the Agency prevent and/or reduce future hazardous occurrences. As such, they are an important element of the HPP.

The COHSR requires employees to report every hazardous occurrence and employers to investigate them in a timely manner. Investigations must be carried out by a qualified personFootnote xxvi with the participation of the workplace committee, and documented in a Hazardous Occurrence Investigation Report (HOIR) to be provided to ESDC as prescribed. The Agency's Policy and Procedures on HOIRR detail the internal procedures and responsibilities to meet the legislated requirements, as well as management's needs. Once completed, HOIRs are to be forwarded to the business unit's senior manager, the workplace committee, the National OHS Program team, as well as to ESDC as prescribed. Finally, the Agency must submit an Employer's Annual Hazardous Occurrence Report (EAHOR) and a Workplace Committee Report to ESDC. This report contains the total number of disabling injuries, deaths, minor injuries and other hazardous occurrences that have occurred in a given year at each of the Agency's workplaces.

Employees, supervisors and committee co-chairs agreed that disabling and minor injuries are well reported using HOIRs, but reporting on near misses and small damages to property could be improved. Some employees do not see value in reporting such occurrences. In 2017, 14 of 33 business units reported no near misses or small property damages for the year, and 7 of the 14 reported none the previous year. While this is possible it is unlikely given the work that Agency employees perform.

In all visited sites, investigations were carried out as required – in a timely fashion by a qualified person with the participation of the workplace committee. All workplace committees as part of our sample reviewed investigation reports. Additionally, in two business units, committee members and supervisors conducted the investigations jointly. Guidance from the Labour Program indicates that both of these methods of involvement satisfy the legislated requirements for committee participation.

|

Business Unit |

BU1 |

BU2 |

BU3 |

BU4 |

BU5 |

BU6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Centralized Database |

11 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

2 |

|

Annual Report to ESDC |

18 |

5 |

1 |

10 |

1 |

5 |

Individual HOIRs and the annual EAHOR are submitted to ESDC as required. However, discrepancies exist between numbers of hazardous occurrences reported annually to ESDC and those captured in the Agency's central database as illustrated in Table 1. Further, a number of incomplete, duplicate and/or incorrect entries were observed in the Agency's database.

Reporting of all hazardous occurrences, including near misses, and data integrity are important as they allow for detailed analysis and informed decision making and support program improvement at the business unit and Agency levels. If the data is not accurate and complete it could lead to poor decisions. This will be addressed through recommendation 4.

5.5 External stakeholders

The CLC imposes obligations on employers when they grant someone access to their workplaces. The Agency grants workplace access to contractors, strategic partners, and volunteers. The Agency must ensure that the activities of these groups and individuals do not endanger the health and safety of Agency employees. Also, the Agency has a duty to inform these stakeholders of any potential hazards within its workplace to which they are likely to be exposed. As per the Agency's OHS responsibilities executive managers are required to ensure that internal and external partners and third parties are informed of the PCA OHS policies and procedures. The Agency's approach with respect to these OHS obligations varies by the type of stakeholder as discussed below.

Contractors

The Agency engages contractors to perform various types of work including construction related work. As previously noted, the Agency does not yet have an internal policy on construction worksite safety despite the increase in quantity and scope of asset projects since 2015. A Construction Safety Standard and guide are under development.

The Agency's Project Management Standard states that compliance with OHS requirements is mandatory and must be enforced by project managers. It does not directly address the need to inform contractors of hazards, but does identify safety as an integral component of all projects.

For smaller Agency projects (i.e. replacing light fixtures), the OHS requirements are not included in contracts, hazards are conveyed verbally but not documented.

Contracts for large Agency-led construction projects include clauses that address the following OHS-related requirements:

- An attestation signed by the Agency and the contractor that all known and foreseeable hazards have been discussed with the project manager;

- Compliance with all federal, provincial/territorial legislation and Agency's policies regarding OHS will be complied with;

- Provision and use at all-times of prescribed safety materials, equipment, devices and clothing;

- Completion of site inspections, hazard assessments and a safety plan prior the project start date; and

- To not endanger Parks Canada employees by their activities.