The Spanish Flu in Canada (1918-1920) National Historic Event

© Library and Archives Canada / PA-025025

The Spanish Flu in Canada was designated as a national historic event in 2018.

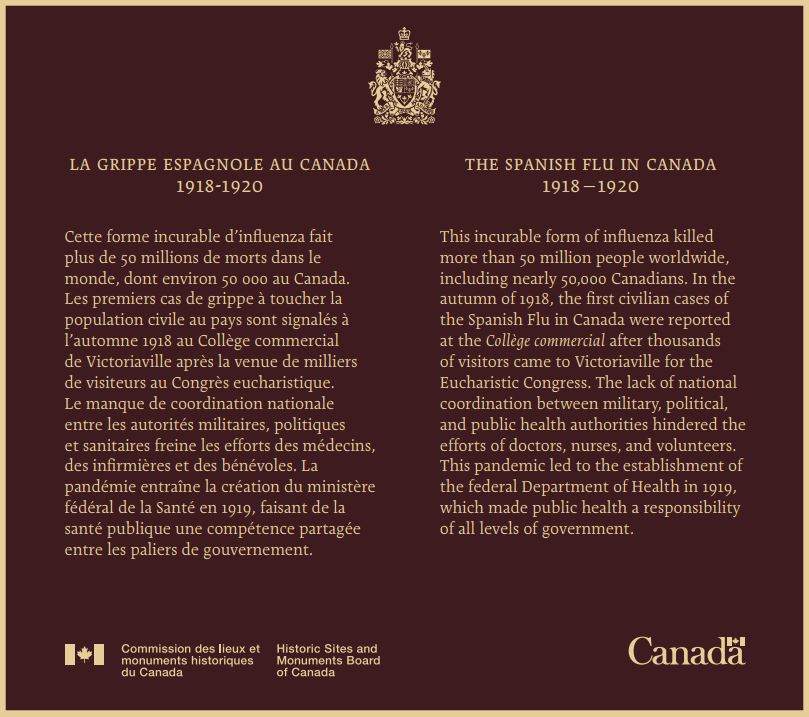

Commemorative plaque: 95 Notre-Dame Street West, Victoriaville, QuebecFootnote 1

The Spanish Flu In Canada, 1918−1920

This incurable form of influenza killed more than 50 million people worldwide, including nearly 50,000 Canadians. In the autumn of 1918, the first civilian cases of the Spanish Flu in Canada were reported at the Collège commercial after thousands of visitors came to Victoriaville for the Eucharistic Congress. The lack of national coordination between military, political, and public health authorities hindered the efforts of doctors, nurses, and volunteers. This pandemic led to the establishment of the federal Department of Health in 1919, which made public health a responsibility of all levels of government.

Spanish Flu in Canada

The virulent Spanish flu, a devastating and previously unknown form of influenza, struck Canada hard between 1918 and 1920. This international pandemic killed approximately 50,000 people in Canada, most of whom were young adults between the ages of 20 and 40. These deaths compounded the impact of the more than 60,000 Canadians killed in service during the First World War (1914-18). Inadequate quarantine measures, powerlessness against the illness, and a lack of national coordination between military, political, public health authorities hindered the efforts of countless doctors, nurses, volunteers, and members of charitable organizations who were risking their lives to ensure that a large number of the ill and their families survived. The Spanish flu was a significant event in the evolution of public health in Canada. It led to the creation of the federal Department of Health in 1919, which established a partnership between the various levels of government and made public health a shared responsibility.

With no vaccine or effective treatment, this devastating pandemic affected every inhabited region in the world, including Canada. It came in multiple waves. The first wave took place in the spring of 1918, then in the fall of 1918, a mutation of the influenza virus produced an extremely infectious, virulent, and deadly form of the disease. This second wave caused 90% of the deaths that occurred during the pandemic. Subsequent waves took place in the spring of 1919 and the spring of 1920. The deaths, estimated between 50 and 100 million, claimed the lives of somewhere between 2.5 and 5% of the global population. Most of the victims were in the prime of their lives.

In Canada, the disease arrived at the port cities of Québec City, Montréal, and Halifax, then spread westward across the country. The intensification of the war effort in the final year of the war was instrumental in the transmission of the disease, as troops travelling from east to west by train, mobilized to participate in the war in Siberia, brought the virus westward with them. Maritime quarantines, which had stopped infectious diseases from entering Canada in the 19th century, did not prevent the spread of the virus as the infected were travelling within the country, where no quarantine measures had been developed. Municipal and provincial authorities tried to save lives by prohibiting public gatherings and by isolating the sick, but these provisions had little effect. As the rates of infection grew, the number of healthy workers declined. Before long, the Canadian economy was paralyzed. Health care professionals were perhaps the hardest hit. Ultimately, it was doctors, volunteers, nurses, paramedics, and members of religious communities who visited those who were ill and their families to deliver modest health care and the supplies needed to survive.

Criticized for failing to provide resources and coordination to public health authorities across the country, the federal government responded to the crisis by founding the Department of Health in 1919.

This press backgrounder was prepared at the time of the Ministerial announcement in 2019.

The National Program of Historical Commemoration relies on the participation of Canadians in the identification of places, events and persons of national historic significance. Any member of the public can nominate a topic for consideration by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

- Date modified :