Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School National Historic Site

The Residential School System is a topic that may cause trauma invoked by memories of past abuse. The Government of Canada recognizes the need for safety measures to minimize the risk associated with triggering. A National Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former residential school students. You can access information on the website or access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-Hour National Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419.

© Sisters of Charity, Halifax, Congregational Archives

The former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was designated a national historic site in 2020.

Commemorative plaque: 47 Indian School Road, Shubenacadie, Nova ScotiaFootnote 1

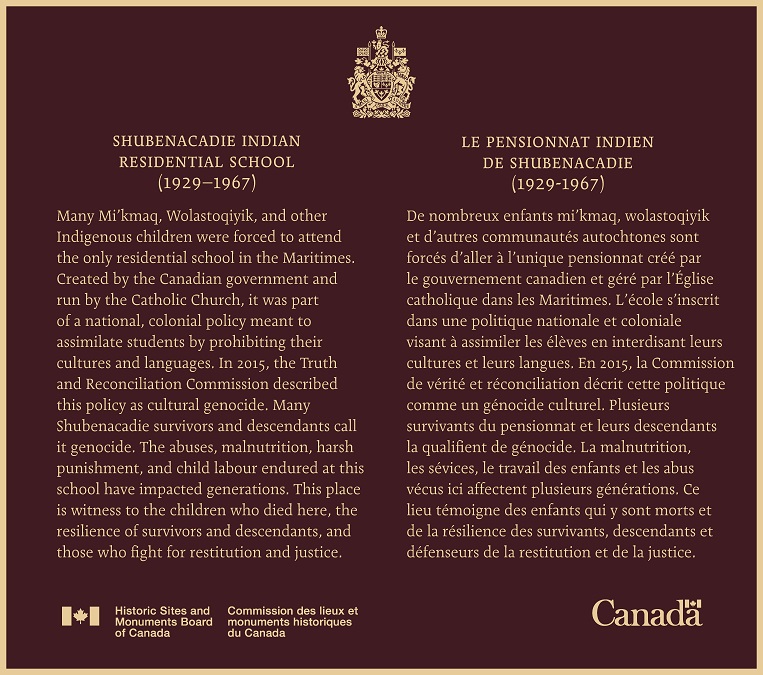

Shubenacadie Indian Residential School (1929-1967)

Many Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik and other Indigenous children were forced to attend the only residential school in the Maritimes. Created by the Canadian government and run by the Catholic Church, it was part of a national, colonial policy meant to assimilate students by prohibiting their cultures and languages. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission described this policy as cultural genocide. Many Shubenacadie survivors and descendants call it genocide. The abuses, malnutrition, harsh punishment, and child labour endured at this school have impacted generations. This place is witness to the children who died here, the resilience of survivors and descendants, and those who fight for restitution and justice.

Mikwite’tmek, We remember: Shubenacadie Indian Residential School

Through a collaboration with Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre, Survivors and descendants share personal experiences of the many ways the residential school sought to take away their language, culture, and way of life. This video is a testament to the resilience of the Survivors of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in the face of this tragic event in Canadian history.

Transcript

[Title appears]

This video deals with topics that may cause trauma invoked by memories of past abuse.

A 24-hour National Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former residential school students and their families. Please call the Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419 to access emotional and crisis referral services.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

We remember.

[Orange flags wave in the grass against a blue sky interspersed with flashes of archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photos.]

(MARY HATFIELD, Shubenacadie Indian Residential School Survivor)

Memories.

They're very important.

It can lead you to a right road or down a wrong road.

[Moody present-day images of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site with faded and tattered orange ribbons interspersed with flashes of archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photos.]

(ROGER LEWIS, Shubenacadie Indian Residential School Survivor)

I think a survivor would naturally, as a defense, kind of take those memories and push them back into the darkness.

[Present-day Shubenacadie River banks and flowing water interspersed with flashes of archival Mi’kmaw history photos.]

However, Mi’kmaw culture is one of oral tradition passed down from generation to generation.

It's how we come to learn how we come to understand, right?

[Modern day Mi’kmaq in regalia dancing at pow wow in Sipekne'katik.]

(MICHAEL R. DENNY, Son of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School Survivor)

So of course, remembering the good things is important,

[The church steps in Sipekne'katik covered in children’s shoes.]

but also remembering the difficulties.

And without that memory our family history, that wouldn't be.

[Time-lapse of the present-day Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site as clouds pass by the hill.]

(DORENE BERNARD, Shubenacadie Indian Residential School Survivor)

We call that ancestral memory.

That's important because it carries our ancestors forward with us.

[Dorene raises archival image of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School exterior in front of former school site.]

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

In order to move ahead I need to know where my family has been.

[Michael holds photo of his dad.]

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

Dad was a survivor of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School.

He got there in late 1949, and he was there as a three-year-old, actually.

They said that he was too young for school, but he was still there.

[Roger holds historic photo of children at Shubenacadie Indian Residential School.]

(ROGER LEWIS)

We often saw kids being taken to the residential school.

But you never thought it would ever happen to you.

Then all of a sudden... they're taking you to the vehicle and you're kind of you know, there's a little bit of reality to this.

I'm going now.

[Archival images of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School exterior.]

A red building with a huge cross on the front of it, the entrance way, the big granite steps and the big oak doors.

[Present-day trees at the front of the former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site.]

Some of the trees are still there.

You could hear the rustle of the wind

[Train tracks in Sipekne'katik.]

Hearing the train whistles in the background as are approaching through Shubenacadie on the way to Halifax.

[Mary holds archival photo of herself as a child with two other Mi’kmaw girls.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

The only thing I remember is walking up the stairs and then taken to the office and where we got registered.

[Vintage doll in a plastic bell-shaped case.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

My mom bought us these dolls. Ball gown dress... in this little plastic bell-shaped case.

And when we got there, those things were taken away.

We thought we would get them back when we left, but we never did.

[Dorene holds archival photo of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School exterior.]

I was four and a half when I went there.

Didn't know that I was staying, so I didn't get to say goodbye.

That was... that was... you know, quite traumatic for me.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

His number was #18.

[Michael holds ribbon shirt showing number 18.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

We all had numbers.

They wouldn't call us by name.

They would call us by numbers, right?

[Archival photos of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School: One shows boys section, the other the girls section.]

On one section was the girls and then on the other side was the boys side.

But we never got to see the boys.

We were separated from the time we entered there.

(ROGER LEWIS)

Yeah, they were other children there besides Mi’kmaw.

[Archival photos of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School exterior with residents assembled on the front steps.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

Two tribes here.

Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqey.

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

Dad said at one point when he was there, there was a couple Mohawk kids that came.

A couple Inuit kids from up north came as well.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

We weren't being treated right.

[Archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photo of children brushing teeth.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

Our routine, was rigid.

You know, we're expected to get up around 6:00 in the morning, make our beds, go to the church.

[Archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photos showing children at church, a cross, children playing outside.]

Church was a big thing.

We had the nuns there and then the priest and what they called brothers.

[Archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photos of grounds and children doing chores.]

No, we never were allowed to leave the grounds at all.

It was not too much idle time, right?

[Archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photos of children eating.]

With the kids eating whatever they're being served. Some of it wasn’t fit to eat.

We're all in bed by seven or eight.

Probably around seven, because it was still daylight.

(ROGER LEWIS)

You didn't have very much interaction with your sisters or cousins.

[Archival Shubenacadie Indian Residential School photos of children lined up shaking hands.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

When we seen each other in the hallway, we had to walk by, not say anything.

[Leather school strap.]

And if we did, we we were strapped and beaten.

And that happened to my brother.

On the way to church one day we met in the hallway and I said ”Hi”, and he said ”Hi”.

[Wooden school pointer stick.]

And he pulled out of line and thrown up against the radiator.

One of the male charges that would take care of the boys was kicking him, telling them to get up.

And I ran out of line and I jumped on him and I started fighting him to get him up.

So we both got in trouble that time.

But that's that's how bad it was.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

Our language defines who we are and they tried to take that away.

[Archival photos of children in classroom learning ABCs.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

They told you not to speak your language or else you're going to be punished.

Yeah.

[Present-day road leading to Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site. Road sign reads Indian School Rd.]

Whenever the parents came to the school there, the nuns would monitor your visitations, I guess, they call it.

And make sure you don't speak your language.

[Archival photos of young boy standing in front of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School out buildings.]

And you're only allowed an hour to visit them.

And then they have to leave again, right?

[Archival photos of girls reading in Shubenacadie Indian Residential School common area.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

I remember being told that we weren't good people and being told that our parents didn't want us.

That's why they we were there.

[Present-day Shubenacadie River shoreline at night.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

I remember crying a few nights, you know, for my mom.

And I would hear the other ones crying too, right?

You couldn't get up and console them because if you got out of bed you got punished.

[Mary walks along a beach looking out to the ocean.]

I remember missing mom, my dad and my siblings.

I miss the freedom ... the beach! (laughs)

Yeah.

[Present-day memorial signpost at Shubenacadie River, arrows indicate other IRS in Canada.]

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

I think the point of, you know, not just the Shubenacadie Indian Residential school,

but residential schools all across Canada, you know, the point was to make us white…

[Archival photos of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School children in uniform.]

…and to get rid of the reserves, to take away our language, to take away our culture

and our customs the way we did things and assimilate us into Canadian culture.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

Our way of thinking wasn't good.

[Present-day pow wow grounds in Sipekne'katik.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

When I was growing up, we never had powwows.

We never had regalias. We never had songs.

[Mary refers to her ribbon skirt.]

We never had dresses like this.

[The church steps in Sipekne'katik covered in children’s shoes.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission described it as cultural genocide.

But the Shubenacadie Survivors, they simply called it genocide,

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

Whether you call it cultural genocide or whatever you may call it,

it was a way to exterminate us,

[Mi’kmaw flag.]

our core, our identity, to wipe that clean.

(ROGER LEWIS)

It wasn't until 1960s that they saw fit to consider…

[Archival image of Canadian Citizenship certificate.]

…Mi’kmaw people citizens of this country.

[An eagle sits in the bare branches of a tree.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

I never tried to leave.

I thought about it. (Laughs)

[Archival image of a police car beacon.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

There are some, you know, families that were arrested at the schools trying to get their kids out.

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

He didn't want to go back.

And so we saw the bus coming and he booked it up the hill.

[An eagle takes flight from bare branches of a tree.]

He stayed there until it was dark.

And that's how he did.

[Archival images of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School classroom and exterior.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

The school had students from 1929 to 1967.

We were the last students to leave.

I was cleaning out the Sister’s locker in her room.

And way in the back, I found my bell doll.

[Vintage doll.]

I told Sister this was mine.

And she said it was hers.

I said, ”Well, you know what? You can have it. I want nothing from here.”

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

My grandmother told me, now that you’re home

You don’t need to speak English. Speak Home.

[Aerial shot of present-day Sipekne'katik.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

When they went home, some survivors felt like they were treated as outsiders or damaged.

[Mary holds archival photo of self and friend as teenagers.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

We've been brainwashed.

Some of them don't want to be known as natives, you know?

It's pretty sad, right?

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

Kids that came back to Eskasoni from Shubie School

they hung out with each other…

[Present-day streets in Sipekne'katik.]

…because the other kids would not, you know, play with them because they spoke different.

[Michael holds photo of his dad.]

My dad, he came back and he spoke English and he was shunned for it, right?

[Dorene holds archival photo of self in her twenties.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

I think each generation dealt with it in different ways.

And mine was to rebel to alcohol and drugs. Yeah.

[Mary holds photo of her grandmother.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

My grandmother - she was quite adamant about keeping our language back then, right?

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

My grandmother told me if I couldn't speak (my) language here speak it up here.

[Mary refers to her head.]

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

What makes us who we are is our language.

Who we are, as L’nu people, is in that language.

[Michael plays traditional hand-drum.]

So when he came back, he started to speak the language again.

(Mi’kmaw drums and singing)

Eventually, you know, he spoke it fluently.

So it didn't work.

You know, they didn't assimilate him.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

Don't ever forget where you come from, where your roots are, and especially your language. Because if the language is gone, who are we?

[Aerial view from highway of former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site showing present-day plastics plant on the hill.]

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

We drove by on the highway.

Dad said:

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

That is where I went to school.

[Aerial view from highway of former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site showing present-day plastics plant on the hill.]

That’s the first time ever that I have a memory of the location of the school.

[Bricks from Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. Archival photo of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School after fire.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

They were in the process of tearing it down when it burned.

The way it was burning - it was like all of those evil things and all those negative things I think were leaving.

[Archival photo of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site post demolition.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

You know, it was mixed emotions, right?

Yeah.

[Present-day views of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School foundation remnants.]

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

But knowing how much pain and how much horror that has caused our people and my family and my dad, I was kind of happy that it didn't exist anymore.

[Aerial view of former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site showing hill.]

(ROGER LEWIS)

Although you don't see the building, the hill is there and it's just as visible in your memory as the school is.

It's a horrible thing that that school was put there.

[Aerial views of former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site showing hill and Shubenacadie River.]

But couldn't be in a more wonderful site than along that Shubenacadie River.

(Mi’kmaw drum plays)

[Aerial view of Shubenacadie River.]

Mi’kmaq played a significant role in the making of this landscape prior to Europeans and throughout that period.

[Historic maps and Mi’kmaw artifacts interspersed with views of Shubenacadie River.]

And it goes back 13,500 years.

It's a continuity.

That whole history and experience unfolding on that river.

Mi’kmaq haven't forgotten that.

[Present-day Mi’kmaq wearing regalia dancing at pow wow. Large drum sprinkled with ceremonial tobacco is hit.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

Pretty soon all our survivors will be gone.

To tell that story we need to leave those things behind for the next generations to carry.

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

I knew eventually the truth would come out about the residential school– and everybody will know.

[Shot showing three Historic Sites and Monument Board of Canada plaques at National Historic Site.]

[Title appears]

The Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was designated a National Historic Site in 2020.

[Men in orange shirts in a drum circle. Young woman in a red dress sings accompanied by fiddler and guitarist.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

We have the commemoration ceremony in 2021 on the first National Day of Truth and Reconciliation on September 30th.

[Details of Historic Sites and Monument Board of Canada plaques highlighting Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey languages and orthographies as well as English and French.]

We unveiled the plaque for the Parks Canada commemoration of the site.

There's Mi’kmaw in three orthographies and two in Wolastoqey.

And then there's, of course, English and French.

So there's three plaques there.

It tells the story about why residential schools were built, the impacts of the residential school on our people and about who we are.

(Song begins: "Sacred Ground / Powwow" - sung by Michael R. Denny)

[Mi’kmaq words printed on card and spoken aloud, with a translation appearing underneath]

This site honors that memory.

This site or this place says we're still here.

[Aerial view of Dorene walking up to plaques at the National Historic Site.]

(DORENE BERNARD)

It's a start towards reconciliation.

[Mi’kmaw Grand Council flag, Canadian and Nova Scotia flags fly beside each other.]

Canadians and all people from around the world that are coming here understand and know the true history of Canada.

[Residential School Survivors, Day School Survivors and relatives of Survivors holding archival photos.]

(MARY HATFIELD)

I think it was pretty important for the people to know.

It's part of the dark history that needs to be told.

(MICHAEL R. DENNY)

We know our history and we know where we've come from.

So we continue on.

(ROGER LEWIS)

Even though they had that dark period,

many dark periods in the past.

[Orange flags flutter in grass on hill. Young Mi’kmaw youth holds up photo of orange flag heart installation at former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School site.]

when I go up there, I reflect back on the ability of Mi’kmaw people to be so resilient through all those difficulties, right?

I think it's just incredible.

[She lowers the photo and smiles to camera.]

I think it's a beautiful story.

[Present-day aerial shot of Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School National Historic Site at sunset.]

[song continues]

END TITLES

This video is brought to you through a collaboration between Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre and Parks Canada.

We are grateful to everyone who shared their time and their stories for this video.

END CREDITS

MI’KMAWEY DEBERT CULTURAL CENTRE LOGO

PARKS CANADA LOGO

GOVERNMENT OF CANADA WORDMARK

The former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School

The former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was the only Indian Residential School in the Maritime Provinces. Built in 1928-29 in the Sipekne’katik district of Mi’kma’ki, near the village of Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia, the school building once stood on a large property that featured barns and other farm buildings, staff residences, cultivated fields, and pastures. The school was established in 1929 and was open to students from 1930 to 1967. The abandoned school building was demolished in 1986 and a factory now stands in its place.

The Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was administered and funded by the federal government and managed first by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Halifax and later the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. It was staffed by the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul of Halifax.

The Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was part of the residential school system whereby the Canadian government and certain churches and religious organizations worked together to assimilate Indigenous children as part of a broader effort to destroy Indigenous cultures and identities, and to suppress Indigenous histories. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission described this policy as cultural genocide. Many Shubenacadie survivors and descendants call it genocide.

Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik children from Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Quebec attended Shubenacadie IRS. Students also came from other Indigenous communities. Many of them were forced to attend. It is difficult to identify all the children who attended the school and determine what communities they came from because records, for this and other residential schools, are incomplete and inconsistent.

Students were subjected to a regimented daily routine that involved hard labour to maintain the school while facing harsh punishments, malnutrition, poor healthcare, nutritional experimentation, neglect, the deliberate suppression of their cultures and languages, and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Some children died while at school.

From the earliest days of the school, students, their families, and community leaders voiced objections, and protested everything from forced attendance to poor conditions, mistreatment, and the inadequate quality of schooling. Many children fought against the system by refusing to let go of their languages and identities. Some children ran away from the school in an effort to return home.

Although the school building is no longer standing, the site of the former school is a place of remembrance and healing for some survivors and their descendants, who wish to preserve Indian Residential School history in the Maritimes. Others, for whom the building and site hold neither healing nor memorial status, believe that the building and site remain a testament and record for the experiences of the children who were there, as well as for the legacies of those experiences throughout Mi’kma’ki. Many are concerned that the long-term intergenerational impact of these experiences on survivors, their families, and communities, will be forgotten. The history of the Shubenacadie Residential School is highly fraught and difficult to construct given the trauma that was, and is, inherent within it. Many survivors are still unable to speak about their experiences.

The co-chair of the Tripartite Culture and Heritage Working Committee of the Mi’kmaq-Nova Scotia-Canada Tripartite Forum submitted a nomination for the designation of the former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School on behalf of the Survivors and their descendants. Parks Canada and the proponent collaborated to highlight the experiences of Survivors and articulate the historic values of the site. The historical report and the plaque text presented to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada were prepared by Parks Canada and the Tripartite Culture and Heritage Working Committee of the Mi’kmaq-Nova Scotia-Canada Tripartite Forum. The Government of Canada announced its designation as a national historic site under the National Program of Historical Commemoration on September 1, 2020.

Backgrounder last update: 2021-09-29

Description of historic place

The Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School National Historic Site of Canada is located in the Sipekne’katik district of Mi’kma’ki, near the village of Shubenacadie in Nova Scotia. There are no standing structures associated with the school, which was built in 1928-29 and was open from 1930 to 1967. Now demolished, it was an imposing three-storey red brick building designed in a Classical Moderne style that followed a symmetrical E-shaped plan with dormitories on each side and a back wing with a chapel. It stood on a large property that featured barns and other farm buildings, staff residences, cultivated fields, and pastures.

After 1967, the site was abandoned and remained unused for nearly 20 years. In 1986, a fire destroyed the dilapidated school building and, two years later, a factory was built where the structure once stood. The formal recognition refers to the factory’s property lines, although the former school site extends beyond these boundaries.

Heritage value

The former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was designated a national historic site of Canada in 2020. It is recognized because:

- although the school building is no longer standing, the site of the former school is a place of remembrance and healing for some survivors and their descendants, who wish to preserve the Indian Residential School history in the Maritimes. Others, for whom the building and site holds neither healing nor memorial status, believe that the building and site remain a testament and record for the experiences of the children who were there as well as for the legacies of those experiences throughout Mi’kma’ki;

- operated from 1930 to 1967, it was the only Indian Residential School in the Maritimes. It was first managed by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Halifax and later the Missionary Oblates of Marie Immaculate, and was staffed by the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul of Halifax and functioned within the residential school system whereby the federal government and churches worked together to assimilate Indigenous children as part of a broad set of efforts to destroy Indigenous cultures and identities and suppress Indigenous histories;

- at this school, Mi’kmaw and Wolastoq’kew children from the Maritimes and Quebec (and possibly children from other Indigenous communities) were subjected to harsh discipline; malnutrition and starvation; poor healthcare; physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; medical experimentation; neglect; the deliberate suppression of their cultures and languages; and loss of life. From the earliest days of the school, students, their families, and community leaders voiced objections, and protested everything from forced attendance to poor conditions, mistreatment, and the inadequate quality of schooling. Children fought against the system by refusing to let go of their languages and identities. Some children ran away from the schools in an effort to return home.

The heritage value of the former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School lies in its powerful connections with past events, and the lived experiences and memories of Survivors. As a site of remembrance, it is a powerful reminder of the pain and suffering endured at the school and evokes traumatic experiences. The site serves as a stark reminder of the Indian Residential School history in the Maritimes and ensures that the history of the Residential School System is known. It is significant because of its association with the Residential School System which has had complex and enduring effects on generations of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children, parents, and communities. This site is a witness to the children who died there, the resilience of Survivors and descendants, and those who fought for restitution and justice.

Source: Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, Minutes December 2019

The National Program of Historical Commemoration relies on the participation of Canadians in the identification of places, events and persons of national historic significance. Any member of the public can nominate a topic for consideration by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Related links

- National historic designations

- National historic persons

- National historic sites designations

- National historic events

- Submit a nomination

- This Week in History

- Government of Canada and the Mi’kmaq-Nova Scotia-Canada Tripartite Forum Commemorate the National Historic Significance of the former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School (News release)

- Plaque unveiling announcement on September 30, 2021 (Facebook) (Twitter)

- Residential schools in Canada

- Former Muscowequan Indian Residential School National Historic Site

- Former Portage La Prairie Indian Residential School in Manitoba

- Former Shingwauk Indian Residential School National Historic Site

- Date modified :