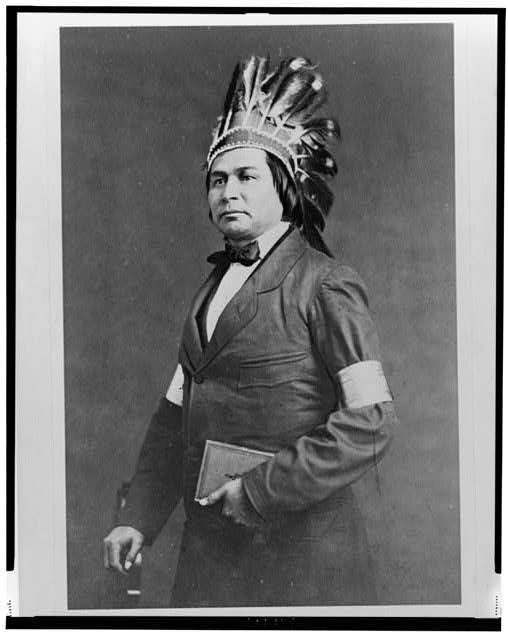

Kahgegagahbowh (George Copway) National Historic Person (1818–1869)

© Library of Congress, Marian S. Carson Collection, LC-USZ62-121977

Kahgegagahbowh (George Copway) was designated a national historic person in 2018.

Historical importance: Mississauga Anishinaabe author, lecturer, publisher, and activist, he gained international literary celebrity as an author of popular non-fiction books in the late 1840s and early 1850s.

Commemorative plaque: No plaqueFootnote 1

Kahgegagahbowh (George Copway)

Kahgegagahbowh (George Copway) was an early Anishinaabe author of popular non-fiction books, which expressed pride in his nation, engaged with Victorian and Romantic literatures to challenge their racism, and offered non-Indigenous readers—in Canada and abroad—important insights into Mississauga spirituality, history, and culture. An international literary celebrity, he contributed to general knowledge of the First Nations in Canada, giving well-attended lectures on Mississauga life to audiences in North America, Great Britain, and Western Europe, and speaking on behalf of Indigenous peoples at the Third World Peace Congress in Frankfurt, Germany (1850). He exemplified the transnational cultural ties and the politicization of Canadian Indigenous authors in the mid-19th century: he leveraged his celebrity to fight for the rights of First Nations in the United States; he helped organize the American Christian Association for Protective Justice to Indians; he used his short-lived newspaper Copway’s American Indian (1851) to challenge the U.S. government; and he petitioned the U.S. Congress in 1850 for the creation of a self-governed First Nations state, called Kahgega.

Kahgegagahbowh was born in 1818. His mother was from the Eagle clan and his father—a medicine man, traditional chief, and veteran of the War of 1812—was from the Crane clan. The family belonged to the nation at Rice Lake (Pam-e-dash-cou tay-ang or Pamadusgodayong) in Upper Canada. Kahgegagahbowh converted to Christianity in 1830, changing his name to George Copway, and four years later left Rice Lake in the company of a missionary party destined for the northern United States. From the American Methodist Church, he received funds to attend the Ebenezer Manual Labor School in Illinois, where he studied from 1838 to 1839. He returned to Upper Canada and married Elizabeth Howell in 1840. Kahgegagahbowh worked for the next five years as a missionary, interpreter, and minister in the United States and Canada. Accused of embezzlement, he was expelled from the church and imprisoned for several weeks in 1846. He left prison determined to write his autobiography.

"The Life, History, and Travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway)" (1847) was popular enough to demand seven printings by 1848 and two revised editions in 1850. Kahgegagahbowh leveraged his new-found celebrity in the United States to petition Washington to support his ambitions for a self-governed First Nations territory (“Kahgega”) that would have eventually achieved statehood, arguing his case to Congress in "Organization of a New Indian Territory, East of the Missouri River" (1850). When his lobbying failed, Kahgegagahbowh returned to writing. He drew from Anishinaabeg and Euro-American cultural traditions to write his pioneering history, "The Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibwa Nation" (1850), a travelogue documenting his popular lecture tours, entitled "Running Sketches of Men and Places in England, Germany, Belgium and Scotland" (1851), and the short-lived weekly, "Copway’s American Indian" (1851), which he published in New York City.

In the years that followed, Kahgegagahbowh struggled to make a living and largely disappeared from the historical record. He died in Ypsilanti, Michigan, in 1869.

Backgrounder last update: 2019

The National Program of Historical Commemoration relies on the participation of Canadians in the identification of places, events and persons of national historic significance. Any member of the public can nominate a topic for consideration by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

- Date modified :