Waterton Lakes National Park

|

Life After Beetle: The Story of Waterton Lakes National Park

|

Waterton Lakes quick beetle facts:

- Mountain pine beetle is a natural part of the forest ecology of Waterton Lakes.

- Half of the pine stands in Waterton Lakes National Park succumbed to beetle outbreaks starting in 1977.

- The most recent outbreak began it's decline in 1984 - 1989.

- 20 years later, forests in Waterton Lakes now show re-growth and diversity.

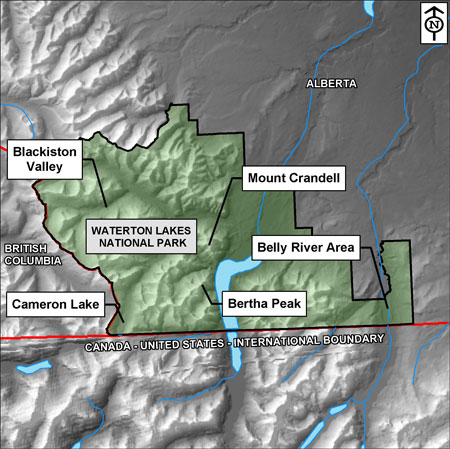

Beetles have a long history in Waterton Lakes National Park and surrounding areas. Outbreaks were documented in the adjacent Flathead area of Montana between 1899 and 1909. It’s likely that these outbreaks overlapped into the Waterton area; however, there is no survey data during this time. Mountain pine beetles were first recorded in Waterton in 1977.

Shortly after their detection, the beetle population grew to epidemic proportions in 1979, rapidly spreading over low elevation pine forests. This outbreak was aided by a series of milder than normal winters that contributed to the survival of young and increases in population. The outbreak, which strarted its decline in 1984, was particularly obvious on the slopes of Crandell Mountain, Bertha Peak, Blackiston Valley, Cameron Lake and Belly River area. After 1984, beetle populations decreased as good habitat - the number of large, mature pine trees - became less available. A return to more normal winter conditions also helped bring about a decline in numbers, until there were no longer enough beetles to be considered an outbreak. Beetles now exist at endemic levels. Waterton Lakes National Park mountain pine beetle outbreak on Sofa Mountain, 1982. Waterton Lakes National Park mountain pine beetle outbreak on Sofa Mountain, 1982.© Parks Canada / Rob Watt |

Sofa Mountain, today's forest, 20 yesrs after mountain pine beetle outbreak. Sofa Mountain, today's forest, 20 yesrs after mountain pine beetle outbreak.© Parks Canada / Rob Watt |

Why was the outbreak in Waterton so big?

In 1977, forest conditions were perfect for a mountain pine beetle outbreak. Much of the park and surrounding regions were forested with mature pine stands that are the preferred food and habitat for the beetle.

The outbreak in Waterton did not happen in isolation. The growth and collapse of the 1977-1984 outbreak was regional in scope. As beetle populations increased and declined in Waterton Lakes National Park, so did populations in surrounding areas. Beetles responded the same regardless of whether they were inside or outside of the park, because the right conditions existed for their growth and expansion.

What do Waterton forests look like now?

Life after Beetle - Forest changes along the east shore of Waterton Lake after mountain pine beetle outbreak. Life after Beetle - Forest changes along the east shore of Waterton Lake after mountain pine beetle outbreak.© Canadian Forest Service / Brad Hawkes |

Over twenty years after the first mountain pine beetle outbreak, the forests in Waterton are healthy. Lodgepole pine is still the dominant tree species in many stands within the park. In areas that were colonized by beetle, the removal of pine trees has promoted a more open mixed forest of pine and spruce in some areas, and pine and Douglas fir in others. Species like spruce, Douglas fir and aspen existed in the park before, but now make up a larger portion of some stands.

Waterton’s forests are diverse and productive habitats with lush understories. Many native species such as woodpeckers, Red-backed voles, martens and MacGillivary’s warblers benefit from this enhanced forest diversity. These changes that occur after a beetle outbreak or a fire are part of a natural process called succession.

Waterton Lakes National Park Mountain Pine Beetle Plots, 2002. Waterton Lakes National Park Mountain Pine Beetle Plots, 2002. © Canadian Forest Service / Brad Hawkes |

Because these forests have aged another 20 years since the last outbreak, trees that were only marginally vulnerable in the late 70’s and early 1980’s are now reaching an age that would make them susceptible to mountain pine beetle. However, because of forest diversity resulting from the last outbreak and fire activity, it is likely there are not enough host pine trees to support an epidemic.

Forest changes after mountain pine beetle outbreak. Forest changes after mountain pine beetle outbreak.© Canadian Forest Service / Brad Hawkes |

1 hectare = 100 metres x 100 metres

1 hectare = 2.47 acres

1 hectare = approximately 2 football fields (side by side)

100 hectares = 1 square kilometre

- Date modified :