Human history

York Factory National Historic Site

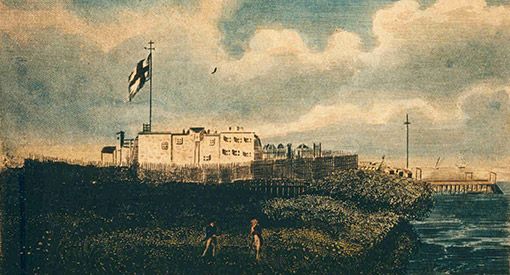

coloured, March 1, 1797.

Between 1684 and its closing 273 years later in 1957, York Factory served as a trading post, distribution point and administrative centre for a vast network of fur posts throughout the West. From 1812 to the late 1850s, it was also the main entry point for European immigration to Western Canada.

York Factory was one of a series of fur-trading posts established in the late 17th century on Hudson Bay by the Company of Adventurers of England Trading into the Hudson's Bay today known as the Hudson's Bay Company.

As early as 1670, an attempt was made by the Company to establish a post at the mouth of the Nelson River, but fierce winds hindered landing and the crew sailed back to England. By 1682, however, three groups of traders from New England, England and France had established a series of fur-trading forts in the area of the Hayes and Nelson rivers to compete for control of the territory and fur trade of western Hudson Bay In 1684, the Hudson's Bay Company built York Fort on the north shore of the Hayes River, eight kilometres upstream from the Bay.

Between 1694 and 1697, the French and English battled for control of the original York Factory. Under the command of Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, the French captured York Factory in 1694, lost it to the English in 1696, recaptured it the following year, and renamed it Fort Bourbon. It remained under French control until the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 which awarded Hudson's Bay Company exclusive trading rights on Hudson Bay. York Factory quickly became the Company's single most important trading post on the Bay, although its monopoly was successfully challenged by traders from New France who had established a series of posts far to the south in the Lake Superior and Lake Winnipeg regions.

Despite diminishing fur returns, the Hudson's Bay Company made no serious attempt to construct any inland posts or to challenge its competitors from New France. With the fall of Quebec in 1760, new merchants - largely Scottish and Métis traders who later formed the NorthWest Company - assumed control of the Montréal-based fur trade and succeeded in capturing much of the trade of the Indigenous peoples who had traditionally made the long journey to York Factory to exchange pelts for European guns, kettles, knives and blankets.

In order to meet its competitors head-on, the Hudson Bay's Company abandoned its sleep by the frozen sea, and in 1774, with the building of Cumberland House in northeastern Saskatchewan, the Company began the construction of a series of inland posts.

York Factory played an important role from the 1680s until approximately 1850, first as a major trading post and then as the main Hudson's Bay Company entrepôt providing the vital link between the vast fur resources of the interior of the continent and the markets of Europe.

In 1810, York Factory became the headquarters for the Hudson's Bay Company's newly established Northern Department. Aside from administrative and financial functions, York Factory also served as the entry point for most Europeans bound for Rupert's Land. York Factory, particularly as headquarters for the Northern Department after 1810, represents the HBC's role as an imperial factor in British North America.

Over the next century, York Factory changed from a fur-trade post to a warehousing and transshipment depot with considerable administrative responsibilities. As headquarters of the Company's vast Northern Department, York Factory at its peak in the mid-19th century boasted over fifty buildings and a large complement of officers, clerks, tradesmen and labourers, as well as a seasonal workforce of Indigenous traders and hunters. With the establishment of new southern supply lines to Rupert's Land after 1860, however, York Factory's role by the end of the century had diminished to that of a regional trading post.

The design of York Factory as a whole was typical of the approach of the Hudson's Bay Company regarding what was appropriate for its posts. Its design was both simple and utilitarian. The buildings of the fort were originally laid out in an "H" shape with the depot building or "Great House" (known in the Cree language as "Kichewaskahikun"), the guest-house, and a summer mess house forming the centre bar. The wings of the "H" were composed of fur stores, provision shops, trading rooms, officers' and servants' quarters. The formality of this scheme was reinforced by the main gate in the encircling wooden palisade being directly in line with the entrance to the depot. Outside of the formality of this public area of the fort the inter-relationship of the other structures further from the river, such as the manufacturing shops and dwellings, was not based on as rigid a plan. Subsidiary buildings were arranged around a network of boardwalks much like the streets of a small village. The boardwalk system in place today replicates the historical circulation patterns and, in combination with the vestigial remains of an extensive system of drainage ditches, provides evocative echoes of the historic landscape and the HBC's response to the environment.

By the 1860s, York Factory comprised over fifty buildings, reflecting the specialized activities of a busy trade centre. Other structures within the palisades included: a doctor's house, Anglican church, clergyman's residence, school, hospital, photographic room, library, cooperage, blacksmith shop, bakehouse, middlemen's dwelling, and net house. North of the fort is a powder magazine, once surrounded by a palisade, and a graveyard.

Throughout the history of York Factory, the involvement of Indigenous peoples has been integral to the operation of York Factory and the fur trade. Initially, the Hudson's Bay Company's trade at York Factory was conducted through Cree and Assiniboine middlemen who acquired furs from tribes living in the interior plains and woodlands. The history of the fur trade was one of cultural and socio-economic interaction between Indigenous peoples and their trading partners (primarily the Hudson's Bay Company). From their initial position as middlemen and traders of commodities, the role of the Home Guard Cree after 1820 gave way to a market function based principally upon the sale of their labour. The immediate area around the Factory was inhabited by the Cree who trapped, hunted and fished for the Company. An Indigenous community was situated one kilometre downstream of the fort. There are also communities scattered throughout the immediate vicinity of York Factory, for example, Ten Shilling Creek, Crooked Bank, Kaska and Port Nelson just to name a few.

The site of the York Factory complex must be considered as a single coherent unit. Its extreme isolation and its original status as the only development for many miles emphasize the value of the historical inter-relationship between individual elements on the site. Only two buildings, two visible ruins, a cemetery, vestigial remnants of planned landscapes and extensive archaeological remains exist today of what was once a large complex.

Related links

- Date modified :