© Alaska State Library, P. Sincic Collection, PCA 75-175

Boat building

Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site

The long portage

For early prospectors and Klondike stampeders, the Chilkoot Trail was a long portage. It allowed them to move their outfits from the coast to the headwaters of the Yukon River.

Prior to the gold rush, prospectors would traverse the Chilkoot Trail each spring and build boats on the shores of Lindeman Lake, part of the Southern Lakes chain – headwaters of the Yukon. Once the frozen lakes melted, they would use the Yukon River – which flows over 3000 km (1800 miles) from the outlet of the Southern Lakes to the Bering Sea – to disperse throughout the interior of the Yukon and Alaska in their search for gold.

The Klondike Gold Rush

When word of the Klondike gold strike reached the outside world in the summer of 1897, a steady stream of hopeful “stampeders” began making their way over the Chilkoot Trail.

After packing their supplies over the 42 km / 26 miles of the Chilkoot Trail, the stampeders still had over 800 km / 500 miles of lake and river travel ahead of them before reaching Dawson City and the goldfields. A few made it to Dawson City in the fall of 1897. Most were halted in their tracks upon reaching the frozen lakes.

Ice bound

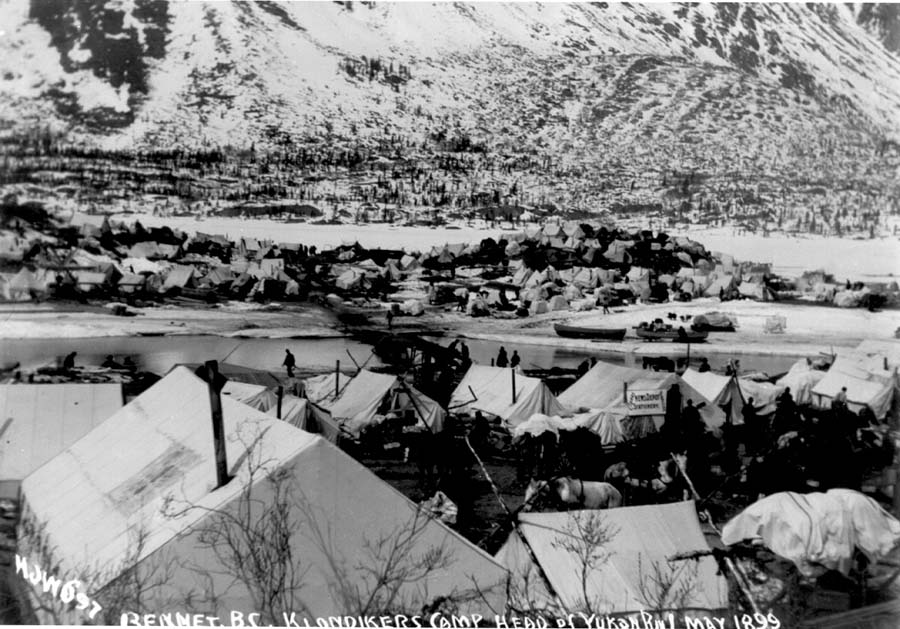

While some of the stampeders built boats at Lindeman Lake, others – faced with the prospect of a long wait for spring break up – chose to push on to Bennett Lake to build their boats. This allowed them to avoid negotiating the rapids on the One Mile River that flowed from Lindeman into Bennett.

Meanwhile, those using the alternate White Pass Trail reached the headwater lakes at Bennett and built boats for the fresh water portion of their journey there as well. As the winter wore on both Lindeman and Bennett became bustling tent cities.

To build a boat

While there were commercial sawmills operating near both Lindeman and Bennett, the cost of milled lumber was beyond the means of most. The majority were forced to resort to milling their own lumber by hand.

This involved laying a log on a scaffold and then sawing the log lengthwise using a whipsaw. It was a two man operation. One man would stand atop the scaffolding straddling the log, while the other would work underneath. The man on top would pull the saw on each upward stroke and guide the saw on the downward cutting stroke. It was both a physically demanding and exacting job. The man on the bottom meanwhile would provide the power for the downward cutting stroke, an equally exhausting job.

For the inexperienced, the physical demands of the job, combined with the inherent difficulty of keeping the saw straight enough to produce a usable plank – plank, after plank, after plank – proved more of a frustration than the hardships of the trail. Klondike Gold Rush journals are liberally laced with accounts of partnerships forged on the trail, dissolving in the sawpits of Lindeman and Bennett. Nonetheless by the spring of 1898 a makeshift armada had assembled on the shores of Lindeman and Bennett Lakes, impatiently waiting for the ice to go out.

Off to Dawson

On the 29th of May the ice began to move. There was a frenzy of activity and within 48 hours over 7000 boats of various descriptions had set off, bound for Dawson City. Some swamped and sank – others were beached – on the stormy lakes. One hundred and fifty more were wrecked – and countless others lost their outfits – in Miles Canyon. But by the 8th of July, the main flotilla had arrived in Dawson City. Their arrival signalled the end of the era of the small hand built scow and ushered in the era of commercial sternwheel navigation on the upper Yukon River .

Related links

- Date modified :