Proposal for consultation: Conservation breeding strategy to rebuild small caribou herds in Jasper National Park

Jasper National Park

This document was written as a preliminary proposal for consultation and decision. This document does not represent the final program plan. Parks Canada is currently updating the program plan based on feedback received during consultations in 2022.

Parks Canada is moving forward with the conservation breeding program. Guidance from experts in caribou ecology and conservation breeding, discussions with provincial jurisdictions, feedback from Indigenous partners, stakeholder and public consultations and a detailed impact assessment informed this decision.

Table of contents

-

Executive summary

Caribou herds in Jasper National Park are at risk

Research and monitoring of caribou in Jasper National Park (JNP) shows that caribou herds have significantly declined over the last half century to very small numbers. Maintaining the status quo will result in the extirpation (extinction within a specific area) of the Tonquin and Brazeau herds in Jasper National Park.

Southern mountain caribou is one of six species identified by the Government of Canada as a priority for conservation action. This priority status is based on their ecological, social, and cultural value to Canadians, and because their recovery can significantly support other species at risk and overall biodiversity within the ecosystems they inhabit.

This document is a proposal for preventing the extirpation of southern mountain caribou in Jasper National Park and rebuilding herds that can persist on their own. It is the product of years of information gathering, observation, and scientific research. Currently, many of the threats to caribou in Jasper are mitigated and conditions are favourable to support caribou recovery. Rebuilding the dwindling herds of caribou in Jasper National Park will help to ensure the continued existence of some of the world’s southernmost caribou.

Parks Canada has acted to mitigate many of the influences on caribou decline

Caribou in Jasper National Park have been listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act since 2003. Over the past sixteen years, Parks Canada has undertaken a series of conservation measures that have reduced human influence on wolf and elk populations, limited the effects of human recreation on caribou, and protected caribou habitat. However, these measures were insufficient to overcome the impact of high wolf density (influenced by historic management practices) on caribou herds before 2014. While wolf density is now naturally at lower levels and conservation measures have reduced the severity of threats to caribou, they are not enough to recover very small herds. When populations are small, they become disproportionately affected by natural processes like predation, disease, or avalanches.

Without intervention, the only two herds remaining within Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit will disappear

The precise size of historical caribou populations within the four herds of the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit is difficult to know. There are clear indications, however, that caribou numbers were much larger and more widely distributed than are seen today.

The Banff herd was extirpated in 2009 and Parks Canada now considers the Maligne herd extirpated, with no sign of caribou in the Maligne caribou range since 2018. At current population levels, the Brazeau and Tonquin herds are not large enough to be self-sustaining (Johnson 2017, Schmiegelow 2017, Hebblewhite 2018). While these two herds have had low but stable numbers since 2015, the number of breeding female caribou is small – an estimated 9 in the Tonquin and 3 in the Brazeau. A caribou population with 10 or fewer reproductive females is considered functionally extinct, even though a small number of the caribou may continue to live on in the herd’s range for a prolonged period (Environment Canada 2011).

Current conditions in Jasper National Park support rebuilding caribou populations

Wolf density has declined to a level below the threshold identified by Environment and Climate Change Canada at which caribou herds can persist. This means that the current wolf population is favourable for caribou survival. Overall, the threats to caribou in JNP have decreased and current conditions support rebuilding caribou populations through a conservation breeding and augmentation program. Through this program, Parks Canada would:

- capture a small number of wild caribou

- breed them in a protected facility

- release young animals born in the facility into existing wild herds

- regularly assess outcomes and adapt management based on research and monitoring

- potentially reintroduce caribou in areas of the park where wild herds have been extirpated

As a first step, the proposed goal for the program is a minimum stable population of at least 200 animals in the Tonquin herd within 5 to 10 years after the first caribou are released. If this first goal is successful, then the possibility of reintroducing caribou in the Brazeau and Maligne herd will be explored, with the goal to reach populations of 300 to 400 caribou total across the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit within 10 to 20 years after the first caribou are released.

A breeding and augmentation program is the best option to prevent the loss of these herds

Parks Canada has explored in detail several options to support caribou recovery. Based on the research and an external scientific review of the evidence for using conservation breeding, Parks Canada is confident that:

- Without our help, the Tonquin and Brazeau herds will disappear and caribou will not return to the Maligne caribou range.

- The threats that originally caused the decline of caribou populations in Jasper National Park are largely mitigated, as a result of our conservation actions and long-term changes to elk and wolf populations in the park, but the Tonquin and Brazeau herds are too small to recover on their own.

- A conservation breeding and augmentation program is the approach with the highest likelihood of success to prevent the disappearance of caribou in Jasper National Park and to meet the goals and objectives of the Recovery Strategy for the Woodland Caribou, Southern Mountain population (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in Canada (2014). Other strategies are not likely to be effective for the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit in the current context.

- A national park is a unique, protected space, where caribou herds have the best chance of recovery and long-term survival. With sufficient habitat and favourable ecological conditions for reintroducing caribou bred in captivity, Jasper National Park could be an optimal location for strengthening southern mountain caribou populations.

- A conservation breeding strategy is feasible and has a high chance of success, building on research and practices from breeding or augmentation of caribou and other ungulates carried out successfully around the world on a smaller scale, as well as similar programs for other species at risk. Chances of success are better while wild caribou remain in the park and their natural behaviours and characteristics can be preserved.

This proposal is intended for many important audiences

This is a technical document, written by and for scientists, wildlife specialists, and researchers. However, it is also intended for:

- Parks Canada, to set out the preliminary plan for a significant and unprecedented conservation program.

- Indigenous people whose history and culture are linked with the caribou and who have been stewards of caribou and other wildlife for millennia.

- partners within the Provinces of British Columbia and Alberta, with whom Parks Canada co-manages transboundary herds and collaborates on caribou conservation actions.

- other scientists and researchers. Parks Canada will need technical expertise and will want to share what is being learned from the work in JNP, so that this work may benefit other caribou conservation programs.

- the Canadian public, for whom caribou are part of our wilderness and our identity.

Note to readers

This preliminary proposal is intended for scientists, decision makers, and stakeholders involved in a potential Parks Canada conservation program. However, we recognize this information is important and of interest to the public. To meet the needs of both kinds of readers, plain-language subheadings summarize all key points and technical terms are defined in a glossary at the end of this document.

-

Defining the issue

Caribou are threatened and declining across Canada

Woodland caribou are declining across Canada, including many regions of British Columbia and Alberta. The herds of caribou that live in Jasper National Park (JNP) are part of a subgroup of woodland caribou, called southern mountain caribou, that have been listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act since 2003 (COSEWIC 2002). In 2011, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada established a new population structure that assigned the herds of caribou in Jasper to the newly designated Central Mountain population (COSEWIC 2011). In 2014, the Central Mountain population was recommended to be listed as Endangered (COSEWIC 2014). However, the Central Mountain herds have not yet been designated on Schedule 1; therefore, caribou in JNP remain listed as “Woodland caribou, Southern Mountain population” (and referred to as southern mountain caribou in this document) and as Threatened under the Species at Risk Act (Environment Canada 2014).

On May 4, 2018, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change determined that the southern mountain population of woodland caribou is facing imminent threats to recovery. The Minister came to this opinion after a scientific assessment of the biological condition of the southern mountain caribou, ongoing and expected threats to their survival, and mitigation measures. The assessment noted a specific concern for ten Local Population Units (LPUs) including the Jasper-Banff LPU (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2018). The Jasper-Banff LPU includes the Maligne, Tonquin, Brazeau, and Banff herds. The last members of the Banff herd were lost in an avalanche in 2009. The last signs of the Maligne herd were observed in 2018 and it is now considered extirpated.

The À la Pêche herd is another threatened southern mountain caribou herd in a separate LPU on Jasper’s northern boundary. This herd is primarily managed and monitored by the Province of Alberta, in collaboration with Parks Canada. Some animals in the herd stay in Jasper National Park year-round, some stay in the foothills of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains, and some migrate back and forth. Blue Creek in Jasper continues to be one of the most important parts of this herd’s range and many animals stay resident in the park year-round instead of migrating outside of federally protected areas. While the herd’s range is impacted by industrial development outside Jasper National Park, this herd is growing as a result of the Province of Alberta’s recovery efforts, including wolf management, outside of national park boundaries.

Two caribou herds in Jasper National Park are on the edge of extirpation

The precise historical caribou population size in JNP is difficult to know because caribou spend most of their time in areas not frequented by people, and consistent measures to count animals were not implemented until recent decades. Nevertheless, there are clear indications that caribou were both more numerous and more widely distributed than we see today.

Records back to the late 1800s refer to “large bands” and areas “thick with caribou.” Caribou were routinely observed in the same locations they are seen today, but were also often seen in the Miette and upper Snaring valleys in the early 1900s and were more widely distributed within the upper Whirlpool Valley (wintering within 10 km of Athabasca Pass in the late 1980s). Stelfox et al. (1974) estimated caribou populations of 220 to 650 between 1915 and 1940, 275 to 525 between 1945 and 1960, and 450 to 711 between 1961 and 1973. Occasional surveys in the late 1980s and mid-1990s indicated that there were approximately 150 to 200 caribou in the Jasper-Banff LPU (Brown et al. 1994, Parks Canada unpublished data).

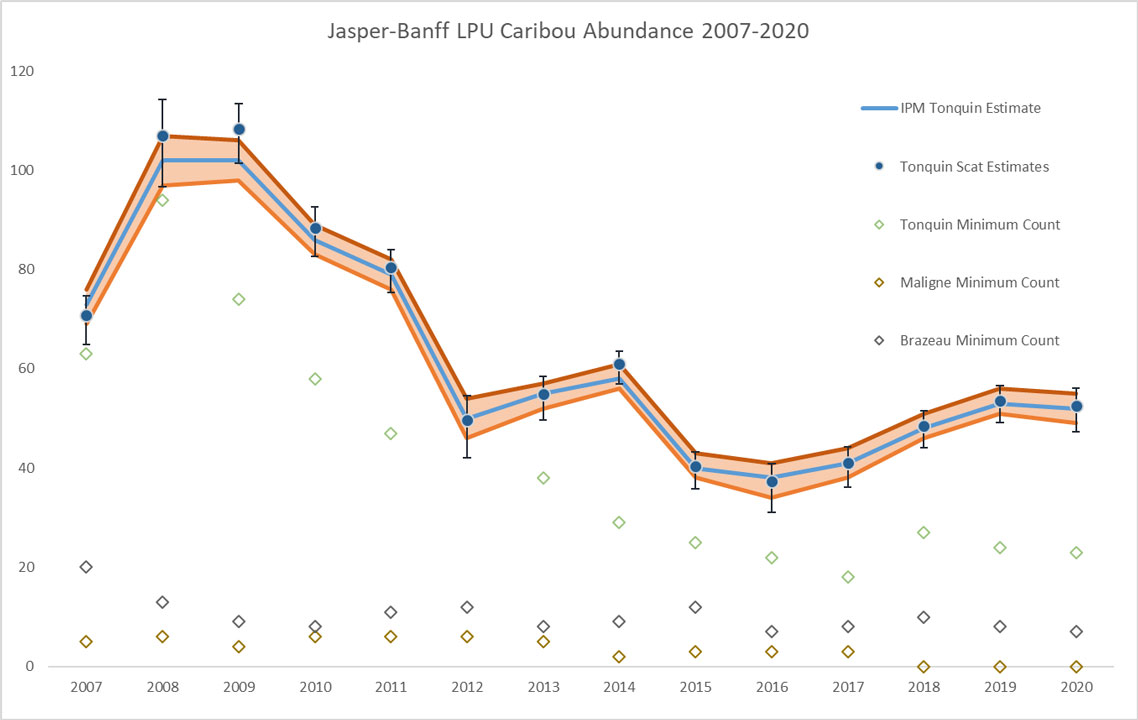

Parks Canada began regular population monitoring in 2002 and has collected information on caribou population size and trends in JNP for nearly 20 years, using consistent and accepted methods (Mercer 2002, Mercer et al. 2004, Whittington et al. 2005, Neufeld 2006, Neufeld and Bradley 2007, Neufeld and Bradley 2009, Neufeld et al. 2014, Neufeld and Bisaillon 2017, Moeller et al. 2018). Parks Canada documented a period of steep decline from 2008 to 2014 in the Tonquin Valley herd, which is now stable at approximately 52 (49 to 55) caribou, but with only 9 adult females in 2020 (Figure 1), a level that is not self-sustaining and below the quasi-extinction threshold (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2018). Population models show that low adult female survival from 2008 to 2014 contributed disproportionately to this decline. High ratios of calves to cows (i.e. high calf numbers) have been observed through to 2020, but because the total number of females is extremely low, high calf ratios are insufficient to grow the population.

Figure 1. Population abundance and trends are expressed as counts and population estimates from an Integrated Population Model (IPM) for the Brazeau, Maligne, and Tonquin caribou herds in Jasper National Park 2007 – 2020 (up to March 2021). Also shown: scat estimates for the Tonquin (error bars are 95% confidence intervals, and orange region 95% credible intervals for IPM estimate).

Text version

Figure 1: A graph showing population abundance and trends for three caribou herds in Jasper National Park from 2007 to 2020 (and up to March 2021). The graph depicts annual minimum counts for the Maligne, Brazeau and Tonquin herds, and population estimates from an Integrated Population Model (IPM) for the Tonquin herd. Scat estimates for the Tonquin herd are also shown.

The trend in the graph shows a steep decline in the Tonquin herd from an estimated 100 caribou in 2008 to a low of an estimated 40 caribou in 2016. Since 2016, the Tonquin herd has been stable or slightly increasing to approximately 50 caribou in 2020. This model trend data for the Tonquin herd is corroborated by minimum counts and scat data.

The number of animals in the Maligne and Brazeau herds is too small to use the Integrated Population Model. Minimum counts show that the herds have both been very small (fewer than 20 caribou) since 2008. As of 2020, there are 0 animals known in the Maligne herd and fewer than 15 in the Brazeau herd.

The Maligne and Brazeau herds have been at or below the quasi-extinction threshold since the mid-2000s. The Brazeau herd has fluctuated around 10 to 15 animals, with very few females, over this time. This number is not self-sustaining and puts the herd at imminent risk of extirpation (DeCesare et al. 2010, Johnson 2017, Schmiegelow 2017, Hebblewhite 2018). The Maligne herd had ten or fewer animals for nearly 15 years and in 2020 Parks Canada determined the herd to be extirpated.

The À la Pêche herd was considered stable from 1988 to the mid-2000s when adult female survival started to decline. In 2016 and 2017, the herd’s population growth rate increased to 14 to 16 percent, likely as a result of wolf control in the region by the Government of Alberta (in part of the range since 2006 and expanded in 2013), leading to higher female survival and juvenile recruitment from a declining growth rate of about 5 percent each year pre-wolf control (Hebblewhite 2018; Eacker et al. 2019). The most recent available population estimate is 152 caribou (Manseau and Wilson 2018).

For more information about population monitoring, see the Jasper National Park Caribou Program progress reports for 2014 to 2016 and 2017 to 2020 (Neufeld, L., and J.F. Bisaillon 2017, 2022). Executive summaries of these reports can be found at parkscanada.gc.ca/caribou-jasper.

Current conditions in Jasper National Park support rebuilding caribou populations

Threats to caribou herds in Jasper National Park are well understood and were recently reviewed as part of a scientific evidence assessment of this proposal (Foundations of Success and Parks Canada 2021). Although many factors combined to cause the decline of caribou populations, the main cause of decline in the Jasper-Banff LPU was high adult mortality as a result of predator-prey dynamics that were altered by wildlife management practices beginning in the 1920s (Bradley and Neufeld 2012).

Through ongoing research and monitoring, Parks Canada has identified five past, current, or future threats for caribou in JNP and undertaken a suite of conservation measures to mitigate them. (For more information about threats and conservation measures see Section 2 - Historical factors in caribou decline in the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit and Section 3 - Current and future threats to caribou in the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit.)

- Altered predator-prey dynamics that increase wolf density and predation on caribou

- Trails and roads that give predators easier access to caribou habitat

- Direct disturbance to caribou by human activity

- Potential for large-scale loss of caribou habitat

- Small population numbers

Overall, the threats to caribou in JNP have decreased. Wolf density has declined to a level far below the identified threshold at which caribou herds can persist (Environment Canada 2014), meaning that the current wolf density is favourable for caribou survival. Factors that increase or bolster wolf density, such as artificially increased elk abundance, have decreased by more than 10-fold over the past several decades, and with no management plans to return to earlier elk densities, it is not foreseen that wolf density will reach levels above the threshold.

Future changes to the predator-prey dynamic because of landscape change, such as those prompted by mountain pine beetle outbreaks and climate change, are largely unknown. While some changes in ungulate and prey populations are possible as a result of wide-spread pine forest mortality in the park, it is unlikely that elk densities will return to the historic highs created by past predator control practices. Wolf density will continue to be monitored as the ecosystem responds to this disturbance. Parks Canada continues to work on vulnerability assessments, landscape scenario modelling, and ungulate response to assess longer-term climate change impacts to caribou.

Herds are so small they will never recover on their own

Since 2015, conditions for adult survival have improved and causes for caribou declines have abated; however, at their current small herd sizes, caribou are disproportionately affected by existing baseline threats, like predation, avalanches, and other stochastic events. While individual caribou may persist in an area for many years, a population with less than 10 reproductive females (such as the Tonquin and Brazeau herds) is considered unable to sustain itself and is therefore functionally extinct (Environment Canada 2011). Maintaining the status quo means that these herds will become extirpated in the near future.

-

Historical factors in caribou decline in the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit

Historical factors in caribou decline in the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit

The most significant factor affecting populations of caribou in the Jasper-Banff LPU over time has been apparent competition, which is similarly the main identified threat for most caribou populations across the country.

Apparent competition refers to an indirect competition between two species that are both preyed upon by the same predator. The predator thrives on its main prey source and when that primary prey source increases so does the predator’s population. As a consequence, predation on the secondary species is increased. Usually, apparent competition affects the secondary species disproportionately, as is the case with the southern mountain caribou.

A common example seen across Canada is an increase in prey such as elk, deer, or moose in an ecosystem, followed by an increase in predators such as wolves, which then affects the predation rate on a rarer species like caribou. Although southern mountain caribou are not the first prey choice for large predators because their numbers are low and they are less accessible, they encounter more predators when predator numbers are boosted by an abundance of elk, deer, or moose (DeCesare et al. 2009).

Apparent competition and changes in predator and prey populations are often caused by human activities that disturb a landscape such as industrial development (disturbance-mediated apparent competition). In the protected landscape of JNP, the cause of altered predator-prey dynamics over the past several decades is not linked to landscape disturbance. Instead, earlier wildlife management practices in the park resulted in flourishing prey populations (management-induced apparent competition), and consequent poor conditions for caribou survival.

Two factors in wildlife management in the past 100 years likely contributed to long-term caribou decline (Bradley and Neufeld 2012):

- Eighty-nine elk were reintroduced to JNP in 1920 - records before this date show few, if any, elk in the area (Dekker et al. 1992).

- Wolves and other predators were shot and poisoned from the moment of this reintroduction until wolf control was stopped in 1959.

Historical reports recorded that “wolves are under control” (Langford 1931), and the “predatory animal situation is well in hand” (Phillips 1937). A small number of wolves likely continued to be present before the mid-1940s despite control efforts. A count in 1943 concluded there were 35 to 60 wolves within the park. A renewed focus and concerted effort to reduce predators continued, with the aid of cyanide guns and shoot-on-sight policies.

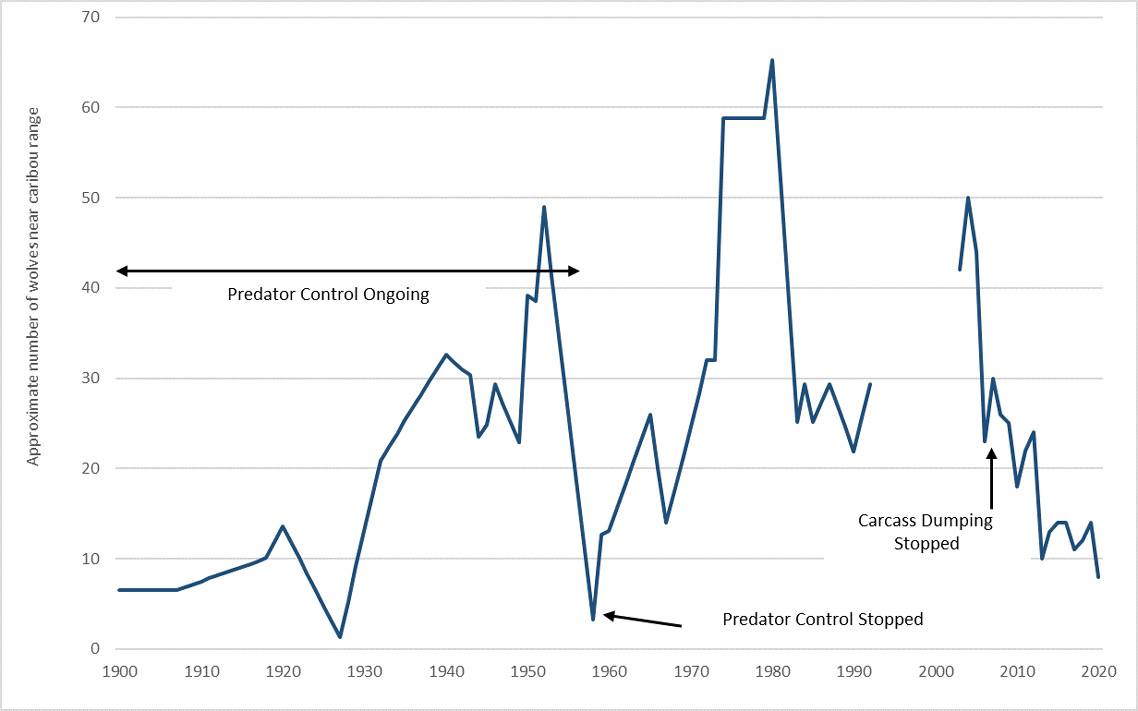

The result of wolf control practices in the park was a substantial increase in the elk population, reaching a height of roughly 3000 elk in JNP in the mid-1930s and maintaining a large population of 2500 in the late 1960s. When wolf control stopped abruptly in 1959, wolves profited from extremely high elk densities and started to repopulate JNP quickly. Wolf densities remained high for many decades but eventually started to decline naturally as elk also declined. A decrease in wolf density was further supported by a change in policy in 2006 wherein Parks Canada stopped depositing road-killed carcasses in gravel pits that were accessible to wolves, which had artificially supported high wolf densities (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The approximate number of wolves near southern mountain caribou ranges in Jasper National Park from 1900 to 2020 (up to March 2021).

Text version

Figure 2: A graph showing the approximate number of wolves near southern mountain caribou ranges in Jasper National Park from 1900 to 2020 (and up to March 2021).

Wolf numbers are estimated to have varied from less than 10 up to 48 between 1900 and 1959 due to varying levels of predator control during this period. The graph shows that in 1900, the number of wolves was estimated to be below 10. Wolf numbers remained less than 20 until 1935. A general increasing population trend reached a high point of around 48 wolves in 1952.

A renewed focus and concerted effort to reduce predators due to rabies brought wolf numbers back to below 10 by 1958. The graph shows that predator control stopped in 1959, which was followed by a steady increase in the number of wolves to a height of more than 60 around 1980. Wolf numbers fluctuated between about 25 and 50 until 2006. The graph shows that in 2006 Parks Canada stopped depositing road-killed carcasses in gravel pits that were accessible to wolves, which had artificially supported high wolf densities. Following this change, wolf numbers dropped steadily to below 10 by 2020.

Caribou minimize their risk of predation by living in areas rarely visited by wolves and other ungulates. Higher wolf density means that wolves are more likely to overlap with caribou habitat, therefore encountering and ultimately killing caribou. During the period of high wolf density between 1959 to 2006, the population and distribution of elk declined. Caribou throughout Jasper also experienced a decline in numbers, but to a much more serious degree.

Due to the elimination of predator control in 1959 and carcass dumping in 2006, along with other actions like moving elk out of the townsite where they avoid predators, prey and predator density have been steadily declining over the past decade to a level that is more suitable for caribou conservation objectives and recovery. Elk populations are estimated to be approximately 300 to 375 in 2018 (depending on which groups are included in the count), and wolf density in Jasper was less than 1.85 wolves per 1000 km² from 2017 to 2020. This density is below the 3 wolves per 1000 km2 recommended by the Government of Canada’s Recovery Strategy for southern mountain caribou as the threshold below which caribou can persist (Environment Canada 2014). Predation (measured by wolf density) is now mitigated as the main cause for the decline of caribou populations in the Jasper-Banff LPU and at a level that will not undermine conservation breeding efforts.

Further reading:

Bradley, M., and L. Neufeld. 2012. Climate and management interact to explain the decline of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in Jasper National Park. Rangifer 32:183-191.

Neufeld, L., and J.F. Bisaillon. 2017. 2014-2016 Jasper National Park Caribou Program progress report. Jasper National Park of Canada, Parks Canada Agency.

Neufeld, L., and J.F. Bisaillon. 2021. 2017-2020 Jasper National Park Caribou Program progress report. Jasper National Park of Canada, Parks Canada Agency. In progress.

-

Current and future threats to caribou in the Jasper-Banff Local Population Unit

The rate of population decline has decreased in the Brazeau and Tonquin herds. However, the Brazeau herd remains perilously small and at high risk of sudden extirpation due to stochastic events and the Tonquin herd does not have enough females to be able to recover on its own. While Parks Canada’s actions have reduced many of the threats to caribou in Jasper National Park, it is possible that the lag time between the implementation of conservation measures and a low caribou population effect played a role in the Tonquin herd failing to recover and/or the conservation measures were ineffective at affecting population growth. Except for small population sizes, threats to caribou have been largely mitigated and current ecological conditions can support a conservation breeding and augmentation program in Jasper National Park, as long as it is implemented with adaptive management. Ongoing monitoring and research to understand the risk of predation on caribou, the impacts of our conservation actions, and the impacts of climate change and other uncertainties will guide how Parks Canada adapts its conservation measures.

1. Changes in predator-prey dynamics can increase predation on caribou

While human activities have altered predator-prey dynamics in the past and led to apparent competition between wolves, elk, and caribou in JNP, both predator and prey populations can also be influenced by other environmental factors including large-scale habitat changes caused by fire, forest insects, climate change, human activities, the introduction of non-native species to an ecosystem, or wildlife management practices. Population monitoring of wolves and ungulates is key to understanding the risk of predation on caribou and how these dynamics shift over time. Parks Canada also continues to work on vulnerability assessments, landscape scenario modelling, and ungulate response to assess longer-term climate change impacts to caribou.

2. Predators can access caribou habitat through human-made trails and roads

Caribou stay in their annual winter range where deep snow makes travel by wolves difficult and inefficient. Predators can gain easier access to a greater range of territory, including caribou habitat, using packed winter trails and plowed roads.

To reduce this threat to the caribous’ winter refuge, Parks Canada has seasonally closed recreational access to occupied caribou ranges since 2014 (and since 2009 for the Edith Cavell area). As of November 2021, there is no access to backcountry areas in the Tonquin, Brazeau, and À la Pêche caribou ranges of Jasper National Park between November 1 and May 15.

Combined with decreasing wolf density, this has significantly mitigated human-facilitated predator access (Neufeld and Bisaillon 2017, 2022). Monitoring shows that wolves are spending most of their time in the valley bottoms and wolves have rarely been documented entering caribou habitat at high elevations at any time of year since 2016. However, wolf distribution can change quickly and have large impacts on small caribou herds in a very short time. Closure changes are continuously reviewed in response to changing conditions and recommendations for adjustments are made based on the most recent information.

3. Human activities and development can have negative effects on caribou

The proximity between caribou and humans can create disturbance mechanisms such as: tourism or commercial activities directly disturbing or displacing caribou, causing elevated stress, or lost foraging or security; development that fragments caribou habitat which limits herd range and isolates populations from other herds; or caribou killed on roads.

Cumulative low-intensity disturbance can contribute to caribou stress (Duchesne et al. 2000) resulting in caribou abandoning range areas (Seip et al. 2007, Sorensen et al. 2008). This is particularly severe during specific activity periods such as spring calving or fall rut.

To minimize direct human disturbance to caribou, Parks Canada has taken steps to restrict the type and timing of human recreation in caribou habitat including winter access closures, discontinuing cross-country ski track setting, eliminating the use of snowmobiles, prohibiting ski lift developments in the Tres Hombres or Outer Limits areas of Marmot Basin, restricting access by bicycle, glider, or motor vehicle, preventing the establishment of new trails, limiting overnight use and random camping, restricting dogs from caribou habitat, and providing education and guidelines for park users and aircraft on ways to avoid disturbing caribou. There are also reduced speed zones on highways frequented by caribou.

4. Potential for large-scale loss of caribou habitat

Caribou are affected when their primary winter habitat (i.e. old-growth forest) is replaced with early seral forests. Critical habitat for caribou in Jasper National Park is identified in the Recovery Strategy (Environment Canada 2014) and is legally protected under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

There are limited developments within national parks that have the potential to cause the loss of high-quality caribou habitat. However, factors such as fires, logging, oil and gas exploration, and development on lands adjacent to the park can have cascading effects on the predator-prey dynamics of animals across boundaries and within national parks.

Threats to caribou habitat in JNP include insects such as mountain pine beetle, altered fire regimes that affect forest succession, and climate change. Collaboration with fire program managers ensures that caribou conservation considerations are included when planning for prescribed fire or wildfire responses. Parks Canada uses an impact assessment process to assess a variety of projects in JNP and their impact on caribou to ensure that habitat requirements are considered for each project.

Climate change may affect caribou by reducing alpine habitats, increasing thermal stress, and/or by affecting the predator-prey dynamic. It could promote the risk of large, stand-replacing fires (McKenzie et al. 2004), which may subsequently affect the predator-prey dynamic or habitat loss. Climate change may also create a mismatch between the caribou life cycle and the phenology of their forage plants (Post and Forchhammer 2008). Climate change may alter snowfall patterns and depths, causing subsequent changes in food availability (especially for arboreal lichen-feeding caribou) and habitat use (Kinley et al. 2006) or increased impacts from avalanches due to unstable snowpack. Climate change could also result in more favourable conditions for diseases and parasites that affect caribou (COSEWIC 2014).

5. Small population size increases extirpation risk

Small population size is currently the most pressing issue faced by the remaining caribou herds in the Jasper-Banff LPU.

Disease, predation, accidents, and random events are part of the natural life cycle; however, their effects on a species become disproportionately amplified as a population gets smaller. The species becomes vulnerable to small population effects. These include:

- difficulty finding mates

- inbreeding

- demographic stochasticity and anomalies (random factors in birth and death patterns – e.g. a random increase in the number of male calves eventually leads to fewer births)

- catastrophic event stochasticity (unpredictable natural events – e.g. a single avalanche in Banff killed the entire caribou population)

- disease

- geographical isolation

- reduced immigration and emigration

As populations decline, they become less resilient to these types of natural events and are more at risk of extirpation and eventually the extinction of the species. Many caribou herds in the southern mountain range are small, and therefore have a very low probability of persistence (Wittmer et al. 2010, Whittington et al. 2011, DeCesare et al. 2010).

Further reading:

Neufeld, L., and J.F. Bisaillon. 2017. 2014-2016 Jasper National Park Caribou Program progress report. Jasper National Park of Canada, Parks Canada Agency.

Neufeld, L., and J.F. Bisaillon. 2021. 2017-2020 Jasper National Park Caribou Program progress report. Jasper National Park of Canada, Parks Canada Agency. In progress.

Foundations of Success and Parks Canada. 2021. Assessing the evidence for adoption of a conservation breeding strategy to enable recovery of southern mountain caribou populations in Jasper National Park, Canada.

-

Proposed solution

Intervention is necessary for the survival of caribou in Jasper National Park

Parks Canada has determined that the use of conservation breeding and herd augmentation could prevent the extirpation of the Brazeau and Tonquin herds of the Jasper-Banff LPU. This intervention would capture wild caribou from the Brazeau, Tonquin, and other regional herds in Alberta or British Columbia, breed them in a facility and release the animals back into the wild. The goal of this program is to add animals to existing wild herds so that they can recover and become self-sustaining.

The Recovery Strategy considers an LPU to be self-sustaining when the following targets are met: the population shows a stable or positive increase in growth over 20 years; the population becomes large enough to withstand random events and can persist over the long term (50 years), and the population reaches at least 100 caribou total (Environment Canada 2014). A recovery goal of 100 animals over four herds (equating to less than 10 females per herd) in the Jasper-Banff LPU, however, is not self-sustaining or historically representative.

A proposed recovery goal for the Tonquin herd is to achieve a stable population of at least 200 caribou. This would allow for natural herd dispersal and migration. Depending on when consultation is complete and facility construction begins, Parks Canada could, at the earliest, bring wild caribou into a facility in Jasper National Park in early 2025. That means the first yearlings born in the facility could be released into the Tonquin herd the following year.

If this objective is reached, longer-term goals will be developed to ensure caribou distribution is restored and maintained within the Jasper-Banff LPU. These goals may include reintroducing caribou into the Brazeau range (which will essentially be extirpated after all of the animals in the Brazeau herd are moved into captivity) and the Maligne range (extirpated), and continuing to augment the Tonquin herd, to reach populations over 300 to 400 caribou across the LPU. Once the program goals are met, the breeding program facilities and infrastructure will be decommissioned and reclaimed within two years. The entire program is expected to span 10 to 20 years from the start of planning to the end of meeting recovery goals.

Alternatives to this proposal have been examined

Alternative strategies to increase the population size of these herds have been examined and are not likely to be effective or feasible as a primary strategy in Jasper National Park.

Status quo (no intervention) and wolf control are ineffective in the Jasper context because:

- the Brazeau and Tonquin herds are too small to recover without intervention.

- wolf control is a short-term tool that is unlikely to recover herds in the Jasper-Banff LPU in the long term.

Current wolf density is low enough that its impact on a self-sustaining herd would be small (Hebblewhite 2018). Temporarily controlling predator numbers without reducing prey density (i.e. elk or deer) would likely lead to a rebound in the wolf population that creates added pressure on threatened caribou populations. This added pressure would re-create the situation of management-induced apparent competition of the past (Bradley and Neufeld 2012). (See Section 2—Historical factors in caribou decline).

Maternity penning is a species recovery technique to increase the survival rate of calves by capturing pregnant females before they give birth. They are temporarily held in a fenced area for four to eight weeks during which calves are born and experience their first weeks of life protected from predators. Maternity penning would not be effective for the herds in the Jasper-Banff LPU because:

- calf mortality is not the cause for declining numbers in the Jasper herds.

- there is an insufficient number of breeding females in the Brazeau and Tonquin herds (Johnson 2017); therefore, preventing deaths of the small numbers of calves that are born is insufficient to recover the herds. In other words, it would add too little too late.

- only a small number of females in Jasper are available to pen and there could be risks from multiple recaptures of those wild females (Johnson 2017, Hebblewhite 2018).

Direct caribou translocation is a species recovery technique that involves moving wild herds (or individuals) from one location to another. Translocation of woodland caribou has been used since the 1930s for several boreal and mountain herds in Canada with variable success (Cichowski et al. 2014, Hayek et al. 2016). Estimates suggest translocation of at least 120 animals would be required to meet the goals of the Recovery Strategy for the Maligne and the Brazeau herds alone. Direct translocation is not considered workable in the Jasper context because:

- almost all southern mountain caribou herds are similarly precariously small and could not provide a sufficient number of caribou for translocation to be effective.

The probability of success for a breeding and augmentation program is high

Parks Canada recommends a breeding and augmentation program as a solution, an approach that is supported by independent external experts and Foundations of Success (Foundations of Success 2021, Hayek et al. 2016, Johnson 2017, Hebblewhite 2018, McShea et al. 2018, Schmiegelow 2017).

Caribou rearing for a large-scale conservation and augmentation program has never been attempted (Hayek et al. 2016). However, the fundamental techniques for successfully implementing a caribou conservation program have been researched, documented, and implemented (Connell and Slatyer 1977, Blake and Rowell 2017, Slater 2017) in different institutions across North America. Several experts note that more is known about caribou husbandry and conservation breeding than many other wild North American Cervidae (Blake and Rowell 2017, Slater 2017).

Jasper National Park offers a uniquely viable location for this program. There is sufficient habitat and favourable ecological conditions for augmentation and reintroduction. And, unlike caribou living in many places across Canada, caribou in JNP do not have to compete with human industry or development for habitat. Acting now maximizes conservation gains for the Jasper-Banff LPU by ensuring the survival of both the Tonquin and Brazeau herds and the greatest genetic retention before herds become smaller. It also maximizes success for long-term population restoration.

In January 2021, Parks Canada hosted a virtual workshop to review the scientific evidence that Parks Canada had developed towards conservation breeding in Jasper National Park, facilitated by Foundations of Success. Following this scientific review by specialists in caribou ecology and conservation breeding, the assessment concluded (Foundations of Success 2021):

- The herds of the Jasper-Banff LPU will be lost under the status quo.

- Threats to caribou (except low population size) have been largely mitigated and should not be a barrier to the success of augmentation and caribou recovery in JNP if appropriate monitoring and management continues.

- Since other strategies to recover caribou populations would not be feasible or effective as primary approaches in JNP, conservation breeding is the approach with the highest likelihood to succeed and therefore should be the primary strategy to recover caribou herds in JNP.

- A caribou conservation breeding strategy, as Jasper's primary restoration tool, is a technically feasible strategy that can lead to the recovery of the Tonquin herd and potentially other herds in the LPU future.

This proposal aligns with Canada’s conservation priorities, Parks Canada’s mandate, and other important goals

Government of Canada

This recovery program will help meet the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada’s priority to enhance the protection of Canada’s endangered species.

Southern mountain caribou is one of six species identified under the Government of Canada’s Pan-Canadian Approach to Transforming Species at Risk Conservation in Canada (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2018a). Caribou across Canada are identified as a priority for government action based on their ecological, social, and cultural value to Canadians. Their conservation and recovery can significantly benefit other species at risk and biodiversity within the ecosystems they inhabit.

Canada’s Species at Risk Act identifies the southern mountain population of woodland caribou as a threatened species. This proposal reflects two important principles from the Species at Risk Act (Preamble, 2002):

- “Canada’s protected areas, especially national parks, are vital to the protection and recovery of species at risk”

- “The Government of Canada is committed to conserving biological diversity and to the principle that, if there are threats of serious or irreversible damage to a wildlife species, cost-effective measures to prevent the reduction or loss of the species should not be postponed for a lack of full scientific certainty”

The broad goals and objectives of the Recovery Strategy guide recovery efforts for JNP (Environment Canada 2014). The Recovery Strategy indicates that for some LPUs with small population sizes, investment in intensive management options (for example, maternity penning and augmentation) may be needed to achieve recovery goals. These recovery objectives include:

- achieving self-sustaining populations in all Local Population Units (LPUs) in their current distribution

- stopping the decline in both size and distribution of all LPUs

- maintaining the current distribution within each LPU

- increasing the size of all LPUs to self-sustaining levels

Parks Canada Agency

The active management of caribou in Jasper National Park to recover a species at risk will protect and improve ecological integrity. This conservation program will also contribute to the Jasper National Park of Canada Draft Management Plan (2021) by ensuring the Multi-Species Action Plan for Jasper National Park (2017) is implemented. The Action Plan is based on the broad objectives of the Recovery Strategy and outlines what needs to be done to achieve the population and distribution objectives for the Jasper-Banff LPU that are identified in the associated Recovery Strategy, including herd augmentation. It also identifies ways to mitigate threats to caribou and protect their habitat.

This goal aligns with the Parks Canada Mandate, the Parks Canada Guiding Principles and Operational Policies (1994), the Parks Canada Agency Departmental Plan 2021-2022 (2021), the Jasper Field Unit Results Plan (2018-2019), and the Multi-Species Action Plan for Jasper National Park (Parks Canada Agency 2017).

Indigenous knowledge, perspectives and practices will be woven into the conservation breeding and augmentation program through collaboration with Indigenous partners. The program will be implemented in a way that addresses the shared interests of Parks Canada and Indigenous partners in caribou stewardship.

The proposal also complements Parks Canada’s external relations and visitor experience goals and demonstrates Parks Canada’s leadership in recovering species at risk. Outreach, education, and off-site interpretation activities on caribou conservation and conservation breeding would be part of the external relations and visitor experience plan for this program.

This proposed approach will be presented to Indigenous partners, stakeholders and Canadians for their input

This proposal is the product of years of information gathering, observation, and research by people who care deeply about the survival of caribou herds in the park. The key to moving forward with this program will be seeking the participation of other people who also care passionately about caribou. All Canadians have a role to play in this important conservation story, in particular:

- Indigenous people, whose history and culture are linked with the caribou and who have been stewards of caribou and the land for millennia, and in particular those Indigenous partners with historical connections to the lands that now form JNP

- federal and provincial governments, Indigenous governments and organizations, academic institutions, environmental organizations, and other organizations committed to caribou recovery

- other scientists and researchers in this field, and

- the Canadian public, for whom caribou are part of our wilderness and our identity

Parks Canada reached out to Indigenous partners of Jasper National Park in the spring of 2019 to seek out early comments on the concept of conservation breeding in JNP. The partners were also asked to identify what kind of participation they would be interested in and any initial priorities or areas of concern. Parks Canada hosted an information session and a site visit at the proposed location for the facility with representatives from nine Indigenous partner groups. Additionally, representatives from three Indigenous partner groups contributed to an archeological survey at the site.

Parks Canada has also shared information about this proposal with neighbouring provincial counterparts and some environmental organizations as part of ongoing dialogue with stakeholders. Parks Canada engaged a variety of government and environmental organizations, academic institutions, and other experts in conservation breeding in a scientific review of the proposal in early 2021 and is committed to communicating about the project regularly.

In August 2021, the Government of Canada committed funding for caribou conservation initiatives in the park. As a result of this funding, Parks Canada has moved forward with developing a detailed design for a facility and beginning a Detailed Impact Assessment process for this proposed project. Indigenous, stakeholder, and public consultation is planned for the Spring and Summer of 2022, with a goal to make a decision about whether or not to move forward with implementing this proposal in Fall 2022. Parks Canada’s decision will consider the results of Indigenous, stakeholder and public consultations, a Detailed Impact Assessment, and further discussions with other provincial jurisdictions. If Parks Canada decides to proceed with this project, collaboration and engagement with Indigenous partners, key stakeholders and the public will continue throughout the life of the project.

Further reading:

Foundations of Success and Parks Canada. 2021. Assessing the evidence for adoption of a conservation breeding strategy to enable recovery of southern mountain caribou populations in Jasper National Park, Canada, page 41.

-

Proposed program plan

Plan objectives

To recover caribou herds in the Jasper-Banff LPU, Parks Canada proposes the following broad objectives:

- Capture remaining wild caribou from the Brazeau herd, a few animals from the Tonquin herd, and potentially several animals from regional herds in Alberta and/or British Columbia over two years and translocate them to a conservation breeding facility (Hebblewhite 2018, McShea et al. 2018). This approach will preserve regional genetics within the captive population that would otherwise disappear. Genetics research is ongoing to determine which source herds would be suitable. Further work with partners is required and forthcoming to determine an approach that minimizes impacts to source populations.

- Establish a conservation breeding herd. Within three years of the first capture, it is expected that this founding herd will have approximately 28 to 32 breeding females. Within five years, it is expected that the captive herd will have 40 breeding females (Neufeld 2019, Neufeld and Calvert 2019). Parks Canada expects to produce 14 to 18 female yearlings every year for augmentation, based on the work of Traylor-Holzer (2015), Blake and Rowell (2017), and Neufeld (2019). Analyses project that 11 to 15 females will be available for release back into the wild annually, while some will be kept in the facility to add to the breeding female stock.

- Proceed with the first augmentation into the Tonquin herd within 14 to 24 months of the first capture of source caribou. The first augmentation will start with a trial of a small number of males (fewer than 10). This step would function as a proof of process before releasing females, who are more valuable for long-term herd recovery. They will join the remaining wild females in the Tonquin herd, who will hopefully help the new animals adapt to the wild.

- Augment the Tonquin herd annually to a total herd size of over 200 caribou within 5 to 10 years after the first caribou are released. Ensure that birth and death rates in the wild are conducive to population stability and simultaneously monitor predator populations in caribou regions.

- Determine whether to begin reintroducing caribou into the Brazeau and Maligne ranges or whether to continue augmenting the Tonquin herd to reach populations over 300 to 400 caribou across the Jasper-Banff LPU within 10 to 20 years after the first caribou are released. Wild-to-wild translocations from the Tonquin herd to the Brazeau and Maligne ranges may be more successful than reintroducing caribou directly from captivity.

- Decommission and reclaim conservation breeding facility and sites within two years of program goals and objectives being reached. The recovery goal for the southern mountain caribou is to achieve self-sustaining populations in all LPUs within their current distribution (Environment Canada 2014). Self-sustaining LPUs do not need ongoing active intervention.

Step 1: Build

Facility design and location

Facility design and construction will consider the project setting and prioritize animal welfare

The detailed planning and design of the facility will involve Parks Canada engaging with an external engineering consultant and partnering with specialists experienced in the planning and construction of similar facilities dedicated to the handling and husbandry of caribou and other ungulate species.

The detailed facility design will incorporate the feedback and mitigations developed during the Detailed Impact Assessment. This will ensure that construction and operation of the facility are executed in a manner that conserves the valued components of the ecosystem and minimizes long-term impacts to the environment. Substantial infrastructure investment and improvements in Jasper National Park in recent years have demonstrated Parks Canada’s ability to execute a project of this scale and sensitivity in such a manner.

Upon completion of the detailed design and impact assessment processes, construction will begin and will consist of several stages, including, at a minimum:

- selective vegetation removal and removal of trees affected by mountain pine beetle within the site

- site preparation including topsoil harvesting, utility construction, earthworks, grade preparation, and road construction

- construction of buildings including an animal treatment lab, handling barn, site office, short-term accommodations space, and vehicle/equipment storage spaces

- installing site furnishings, including construction of site fences, animal feeders, waterers, and site security infrastructure, and

- construction restoration and reclamation.

At all times throughout the design and construction processes, the welfare of captive caribou will remain the highest priority of engineers, planners, and decision-makers.

Facility design will be research-based to maximize caribou health

This facility will house more than 100 animals at peak production times, specifically in the early summer months. The facility will be made up of fenced pens, which will support herd management, protect against predation, and allow for basic handling and animal health care. The facility will be designed to be decommissioned at the end of the program’s lifecycle. Parks Canada has engaged with experts with more than 25 years of experience managing caribou in captivity (Blake and Rowell 2017) and involved in caribou health care (Slater 2017) to create husbandry and health care protocols that would govern the facility’s operations.

The breeding facility requires approximately 65 to 80 hectares of land to allow for herd management and to accommodate separating animals at various life stages and times of the year, as well as for health care and to provide quarantine areas. The facility layout will limit negative interactions among animals and provide acceptable overall density. The facility would include approximately 10 hectares for calving pens to hold cows and their calves for roughly 10 days after birth. Limiting the use of the calving pens and density of caribou within the pens will be critical to minimize calf mortality.

Because the facility will handle caribou at a higher density than found in nature, facility personnel will minimize the associated risks using strict handling, herd management, and health care protocols (Blake and Rowell 2017, Slater 2017). Based on these design inputs and animal husbandry protocols, and with the aid of caribou husbandry experts, a comprehensive list of facility requirements has been developed. Detailed planning and design of the facility was initiated in the Fall of 2021 and should be completed during the Summer of 2022.

A facility in Jasper National Park maximizes chances for success

Jasper National Park is the best location for the program’s success based on a list of criteria that were applied to a variety of proposed sites (Wilson 2018). Parks Canada recommends a site along the Geraldine Road, 30 km south of the Jasper townsite. The proposed site within JNP is:

- relatively quiet with low human disturbance

- close to typical caribou habitat

- able to supply environmental conditions similar to those found in their natural habitat (i.e., temperature, vegetation, water sources)

- distant from large concentrations of other wild ungulates

- entirely separate from domestic livestock

- relatively close to source sites for wild caribou and release of captive-reared caribou

- relatively close to utilities and services required to run the facility, and

- accessible to Parks Canada staff from the Jasper townsite.

Ambient conditions at the proposed Geraldine Road site in JNP, such as temperature and vegetation, are most like those of planned release sites. A site in JNP benefits from its proximity to both capture and release sites, which minimizes transportation of caribou and reduces acclimatization stresses, and is likely far enough to minimize the risk of caribou returning to the facility. It also offers adequate drainage and protection against predators.

To provide shade, the facility would be situated in a forested area and the fence lines and site preparation will be designed to preserve as many trees as possible (Blake and Rowell 2017), while mitigating the risks of dead trees that have been affected by mountain pine beetle. The facility will include additional heat protection such as open-side shade shelters and cooling stations with water sprinklers to protect the caribou on hot days. Shelters and sprinklers have been used successfully in other breeding operations to assist caribou in thermoregulation (Blake and Rowell 2017). A cool air temperature was one of the key criteria for determining acceptable locations for the facility.

Preliminary site investigation work at the Geraldine Road site has included verifying a clean and reliable water source (by drilling and testing an underground well), collecting a 3D topographic survey of the area, and determining the incidence of any rare plants within the estimated project footprint that require environmental mitigations for protection. Several Indigenous partners to Jasper National Park also took part in a visit to the site in September 2019 and representatives from three Indigenous partner groups contributed to an archeological survey of the site.

Relative proximity to the Jasper townsite is important for fast and ongoing access for professionals working at the site. Distance to veterinary care is a critical factor, as any delay in identifying and responding to health problems or issues with birthing may reduce successful outcomes (Macbeth 2015). Blake and Rowell (2017) suggested that a lead veterinarian need not be on-site full time and that the position could be filled by someone working remotely, as long as a large animal veterinary practitioner was nearby to address minor health issues and to supply basic obstetric assistance. This resource is currently available in Jasper.

Compared to more remote locations, the proximity to Jasper will facilitate collaboration with academic partners, increase staff retention, increase efficiency by reducing travel time, improve access to reliable water and power sources, and simplify operations of the facility by reducing shipping time and delays for maintenance work.

Other sites were considered and rejected, primarily because of disease risk

Several potential breeding facility locations outside of JNP were considered based on an extensive criteria list, including Elk Island National Park, Ya Ha Tinda Ranch, and public land in the Hinton, Valemount, or Calgary areas. All were rejected as sub-optimal (Macbeth 2015, Bisaillon and Neufeld 2017, Bisaillon et al. 2016, Blake and Rowell 2017, Slater 2017, Whittington et al. 2011, Wilson 2018).

One key reason that these sites do not meet the criteria for a breeding facility is exposure to disease. Disease risk is a major deciding factor for success in all conservation breeding programs (Ballou 1993, Snyder et al. 1996, IUCN/SSC 2014). The risk of chronic wasting disease, one of the most serious health concerns for ungulates, increases significantly east or south of JNP (MacBeth 2015, Helen Schwantje, 2017, pers. comm., December 2017, and Sue Cotterill, 2019, pers. comm.). Potential sites inside JNP do not have a history of agricultural use nor any known history of significant endemic wildlife diseases (Macbeth 2015, Slater 2017; 2018, Wilson 2018).

Distance from urban centres is an advantage for success but has associated costs

Note that building a facility in JNP is estimated to have a higher cost than other locations to construct and decommission, as well as for rehabilitating habitat at the end of the program (Wilson 2018). However, while sites near urban centres benefit from lower building costs, they increase stress on caribou due to transportation time and increased risk of disease.

Step 2: Capture

Securing source caribou

Securing source caribou will involve capturing wild caribou and transporting them to the conservation breeding facility. The goal is to obtain caribou from source herds with the closest genetic and behavioural match to the wild herds where the animals will be released, and research is ongoing to inform this. It is imperative that source herds not be imperiled as a result of moving females from source herds into captivity and further analyses with partners will consider this critical factor. Risks associated with capture, handling, and transport of caribou would be mitigated by employing established best practices from other caribou capture, captive rearing, and translocation programs (Slater 2017).

Source herd options are limited given the precarious state of most herds, and genetic and behavioural differences between herds must be considered. Details on how many caribou and from which herds source animals will be drawn from are not yet confirmed - decisions will be based on the best available information about genetic and behavioural suitability, analyses informing the impacts of removing animals from source herds, and working relationships with provincial and Indigenous partners. Initial population modelling to identify impacts to source herds (Neufeld and Calvert 2019) will be further assessed in collaboration with provincial partners and academics in 2022-2023.

Genetic diversity of the breeding herd is a critical consideration

Parks Canada aims to maximize genetic diversity, maintain locally adaptive genetics, and mitigate the risk of future inbreeding depression. For females, this can be done by capturing caribou from different areas and regularly assessing genetic relatedness in the breeding herd to ensure genetic goals are being met (Blake and Rowell 2017, Cavedon and Musiani 2020). For males, Parks Canada can track the number of offspring from each male breeding caribou, limit the time males breed to control the number of offspring produced, and add new wild males to the breeding herd periodically (Traylor-Holzer 2015). This genetic strategy will ensure that genetic diversity is maximized and not impacting production or landscape genetics (McShea et al. 2018).

To maximize genetic diversity in the captive population, Parks Canada would:

- assemble as large a breeding population as possible (while minimizing impacts to source herds) and quantify initial genetic parameters

- identify and address problems in the founding population through ongoing genetic review and individual caribou management

- minimize genetic relatedness among wild-caught animals (i.e., capture from several source herds, capture caribou from different areas within a single large-source herd)

- replace older breeding males, that are less consistently virile, with new wild-caught males rather than captive-born males when feasible

- select captive-born males that are the fewest generations removed from the wild source caribou

- place breeding males with a different group within the captive population than the one into which they were born

- manage breeding group size, and

- limit the time that males breed to balance the number of offspring produced by each male.

The near-extinct Brazeau herd and animals from regional herds are proposed to form the founding breeding herd

Since the Brazeau herd is well below quasi-extinction levels and facing imminent extirpation, Parks Canada proposes capturing this herd and relocating the animals to the conservation breeding facility (Slater 2017, Hebblewhite 2018, McShea et al. 2018). In addition, the plan proposes capturing and translocating a few males and potentially a few females from the Tonquin herd to the conservation breeding facility, which could preserve local genetics within the captive population that may otherwise disappear.

In addition to the Brazeau and Tonquin caribou, Parks Canada would ideally capture 25 to 35 caribou from a mix of regional populations such as the À la Pêche or Columbia North herds (to be determined after forthcoming analysis and discussions with partners), to help populate the founding herd. Parks Canada may translocate small numbers of caribou from multiple and various wild or captive sources for genetic diversity and to decrease the impact on any one herd. In addition, caribou from other herds that are functionally extirpated could also be used in an effort to preserve the animals and their genetics. Caribou from the source herds would be primarily females, plus calves if they are still at the heel, and two males over one or two years, biasing toward younger animals (Hebblewhite 2018, Neufeld 2019). Additionally, to help reduce impacts to source herds, translocating captive-born caribou back to the source herds will be recommended in later years of the project.

The capture of source animals would occur between December and February. It is recommended that founding source animals be captured over two years. While it is possible to capture all the breeding females in the first year, this strategy could have several negative outcomes. Capturing all animals in the first year would require a more aggressive capture and transport schedule, and would be a greater risk to the caribou with only one breeding group (i.e., disease or other problems could affect this one group catastrophically). Capturing females over two years maximizes the short-term conservation of genetic retention and animal rescue while minimizing risks (e.g., cost, transport, animal health, and welfare). A two-year process allows Parks Canada to learn from the first capture year to verify success and apply the learning to the second and following years. It also allows for proof of program effectiveness for stakeholders and the public and more time to communicate about the process as it unfolds.

Step 3: Grow

Breeding caribou in captivity

By managing risks, captive rearing has the potential to supply enough caribou to meet or exceed the goals of the Recovery Strategy for the herds of the Jasper-Banff LPU (Johnson 2017, Schmiegelow 2017, Hebblewhite 2018). The program aims to produce 14 to 18 female yearlings annually, with most (11 to 15) available for release (Neufeld 2019). Research indicates that 10 to 20 females per year is possible. Actual numbers will depend on reproductive rates, first-year mortality, and adult mortality in captivity, which are a function of good husbandry, facility management, captive conditions, and expertise (Whittington 2014, Traylor-Holzer 2015, Blake and Rowell 2017). To meet the objectives of the program, Parks Canada must minimize mortality at all stages.

Adult female survival in captivity is the most influential factor in producing calves for release, based on population viability analysis (Whittington 2014, Neufeld 2019). Without high adult female survival in the facility, more calves would need to be kept in the facility for breeding. Maintaining an annual survival rate greater than 96 percent would produce the maximum number of yearlings for release. This high-productivity scenario is likely possible if strict health and husbandry protocols are implemented and closely monitored (Blake and Rowell 2017).

Maintaining diversity in the breeding program will require a clear breeding plan, pedigree tracking, and metrics to monitor overall diversity (Blake and Rowell 2017).

Managing health and disease risks will be critical to maximizing the program’s productivity

Managing caribou health is essential to the program and will achieve recovery objectives faster. The facility design limits the number of caribou that can be held at one time. Proper husbandry will also be extremely important. A program to manage animal health should be based on preventive actions rather than medical intervention.

Drawing on knowledge from other successful captive ungulate practices, breeding females must be habituated to humans to:

- reduce the animals’ overall stress levels

- enable handling to monitor their health

- reduce the likelihood of trauma events from stressed animals

Calves and yearlings require a more hands-off approach to prepare them for release into the wild. Cows with calves should be handled with minimum intervention, and calves may be raised separately from cows after weaning (Blake and Rowell 2017). Indigenous partners have identified the importance, and challenges of, raising caribou to be wild. Their connection to caribou and experience with animals will be beneficial to adapting approaches to breeding and augmentation.

The captive herd is expected to have approximately 40 adult breeding females and 8 to 10 adult males. The program will be able to control density in the facility (which is important both for cost and animal management reasons) based on when the yearlings are timed for release.

Male yearlings will likely be released in late spring at the age of approximately 10 months, which also helps decrease caribou density in the facility before the next year’s calves are born. Female yearlings would likely be released in September or October, at the age of 15 months. This will allow females time to bond with their rutting groups when social grouping behaviours are at their strongest. This will also reduce predation risks to released calves because bears will have started denning and wolves will have limited access to caribou habitat in winter due to snow.

This proposed release schedule would reduce husbandry costs and ensure low animal density in the facility (Blake and Rowell 2017). It also allows the program to draw lessons from male releases and make any necessary changes to maximize success when releasing female yearlings. Based on this timing, capacity for 100 to 120 animals in the facility is required to ensure that animal density is kept low and resources are not strained (Blake and Rowell 2017). Any overflow capacity requirements could be met with extra unassigned pens or building additional pens within the footprint of the site.

Further reading:

Blake, J. E., and J. E. Rowell. 2017. Assessment of a Conceptual Design and Development of a Management Strategy for a Woodland Caribou Captive Breeding Facility in Jasper National Park. Fairbanks, Alaska

Macbeth, B. J. 2015. A Health and Disease Risk Assessment for Parks Canada's Proposed Mountain Caribou Captive Breeding Program. Parks Canada. Canmore, Alberta

Neufeld, L. 2020. Population Modelling to Assess Recovery of the Tonquin Caribou Herd: Combining a captive projection model with an integrated population model for the Tonquin herd. Jasper, Alberta.

Slater, O. 2017. Health Monitoring and Herd Management Strategy for Woodland Caribou Captive Breeding, Jasper National Park.

Slater, O. 2018. Addendum: Health Risk Assessment for a Mountain Caribou Captive Breeding Facility in Jasper National Park or Calgary, Alberta.

Traylor-Holzer, K. 2015. Woodland Caribou Captive Population Model: Final Report. International Union for Conservation of Nature, Breeding Specialist Group.

Watts, S.M. and A.T. Ford. 2019. Review of: “Assessing Recovery of the Tonquin Caribou Herd Combining an In-Facility Caribou Population Model and Caribou Integrated Population Model.” Kelowna, British Columbia.

Step 4: Release

Release into the wild

With the main threats causing caribou decline in Jasper National Park mitigated (Schmiegelow 2017) and favourable ecological conditions and habitat in the park, the probability for successful augmentation or reintroduction is high. Under the present scenario, the Tonquin herd will be the only herd with extant animals and will therefore be prioritized for augmentation (Hebblewhite 2018, McShea et al. 2018).

Selecting the right recipient herds and timing the release of captive-bred animals is crucial to achieving the program’s objectives and minimizing mortality after release.

Captive-breeding programs generally use either a hard release or a soft release strategy.

A hard release may create higher post-release mortality

A hard release occurs when animals are transported to the site and immediately released into the habitat (for example, translocation and release) without temporary protection from predators, supplemental feeding, or time to adapt to their unfamiliar environment. This approach is less costly and is a potential option for an extant, resident herd of caribou. However, this approach can result in high post-release mortality if either the released animals have no herd to join, or it is unlikely that they will join a small extant herd within the weeks following release. Some studies (e.g. Kinley et al. 2010) have documented successful hard releases. This approach, however, is not recommended for this program.

A soft release includes transition time at the new location

A soft release entails holding the translocated caribou at the release site in a temporary pen where they are fed and protected from predators while they have an opportunity to acclimate to their new surroundings. Caribou are typically held for about three weeks. Wild animals from the recipient herd can also be brought into this pen to bond with new animals. A soft release is likely to result in a greater survival rate of yearlings and increase the success of augmentation (Slater 2017).

A soft release strategy is the preferred option, but the approach may vary based on conditions

Based on recent examples of translocation using hard release elsewhere, Parks Canada prefers a soft release option despite the added cost and associated logistical complications. A soft release provides better group cohesion, especially if caribou from the extant herd are present in the pen. A strong herd instinct keeps caribou together. Developing this instinct among released captive animals and wild recipient herds is thought to increase the integration of released animals into extant herds (Blake and Rowell 2020, pers. comm., April).

Based on the timing of the release, seasonal herd movements, and existing infrastructure required to support a soft release strategy in the Tonquin, the release pen for female calves will be in the Tonquin Valley and the release pen for male calves will be located in the Edith Cavell area, although both locations require further assessment.

Indigenous partners have noted that animal care practices, as well as ceremonies, have a significant role to play in helping captive caribou accept their release area as their new home. The partners also identified considerations about working with the caribou’s instincts to return to their home range.

Note that this program will include several release sites, each with its own environmental and access conditions (for example, snow, predator densities, extant caribou, and road availability). Further details about Parks Canada’s soft release strategy, including fence design, transport methods, on-site management, and cost, will be determined further along in the planning process.

Further Reading:

Parks Canada. 2019. Draft Release Plan for Captive-Bred Caribou into the Tonquin Valley.

Step 5: Adapt

Research, monitoring, and adaptive management

Conservation breeding of caribou will be a major conservation initiative for Parks Canada and understanding its successes and failures will be critical to adaptively managing the program. A dedicated research and monitoring program is critical to creating a foundation for evidence-based decision-making and adaptive management.

The program will be guided by Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation, which provides a framework to define and achieve conservation outcomes. Parks Canada will independently engage research scientists to test hypotheses and assumptions, gather data and knowledge, and learn from and integrate results throughout the program’s implementation. The program may also be guided by scientific advisory committees (see the section on Governance below) composed of experts in conservation from around the world. Additionally, Parks Canada will collaborate with Indigenous partners to weave Indigenous knowledge and practices into the program.

The information gained throughout this conservation breeding program will have benefits beyond adapting and evaluating the program itself. The results from research and monitoring as well as lessons learned throughout the program can be shared with other recovery programs. Close collaboration with other programs and fora has the potential to support caribou recovery and other species at risk programs across Canada and around the world, regardless of the outcome of this program.

Step 6: Nature takes over

End and decommissioning

Parks Canada will discontinue the augmentation program after there is sufficient time to evaluate the program and determine whether the objectives have been met. Parks Canada will need to define a point at which to end the program if mortality in captivity is higher than expected, if augmentation or reintroduction efforts fail, or if funding or support is withdrawn. If this were to happen, animal care and health considerations will be central to phasing out the program.