Spiral Tunnels

Kicking Horse Pass National Historic Site

Background

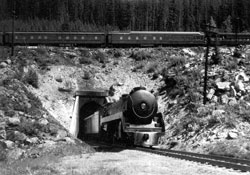

Steam train spiraling over itself © Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies NA71-5409

When British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, it was on the condition that Prime Minister John A. Macdonald would build a railway to link the province to the rest of the country. Building a railway across such a large continent was a major undertaking and one of the most serious obstacles was the Rocky Mountains. Several passes were considered for the route and despite its rugged terrain, Kicking Horse Pass was chosen because of its proximity to the US border and its shorter distance to the Pacific Coast. This choice was so significant to the history of Canada that Kicking Horse Pass was designated as a National Historic Site in 1971.

The "Big Hill"

Main track with spur line to the right

The steep grade in Kicking Horse Pass posed a serious challenge. Under government pressure to complete the railway, and given the engineering challenges that came along with the geography, Canadian Pacific (CP) was not in a position to carve a gradual descent. A solution was reached, which temporarily allowed a grade of 4.5%. The first train to attempt the hill in 1884 derailed, tragically killing three workers. In an effort to improve safety, three spur lines were created to divert such runaway trains on what became known as the “Big Hill”. Switches were left set for the spurs and were not reset to the main line until switchmen knew the oncoming train was in control. Descending the Big Hill was challenging, but uphill trains had their problems too. Extra locomotives were needed to push the trains up the hill, causing delays and requiring extra workers. Although the mountains were a complication for CP, they were an inspiration to the many tourists who started to arrive by train. In an effort to preserve the landscape and encourage tourism, CP prompted the creation of Mount Stephen Dominion Reserve in 1886. The park was renamed Yoho in 1901.

Schwitzer’s solution

The solution for a more gradual grade came from J.E. Schwitzer, one of the railway’s Assistant Chief Engineers. He modeled the Spiral Tunnels after a system used in Switzerland. In 1909 the Spiral Tunnels were completed and after 25 years of use, the Big Hill grade was abandoned. With a gentler grade, descents became safer and slower, spur lines and rear pushers were no longer necessary, and scheduling delays and operating costs were reduced. Although the Spiral Tunnels were a great improvement for the grade, rockfall, mudslides and avalanches are some of the challenges we still face today in this area where nature reigns supreme.

How the Spiral Tunnels work

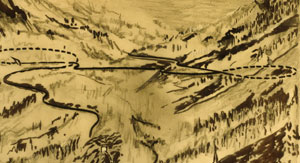

Dotted lines are the Spiral Tunnels

An eastbound train leaving Field climbs a moderate hill, goes through two short, straight tunnels on Mt. Stephen, under the Trans-Canada Highway, across the Kicking Horse River and into the Lower Spiral Tunnel in Mt. Ogden. It spirals to the left up inside the mountain for 891 metres (0.6 miles) and emerges 15 metres (50 feet) higher. The train then crosses back over the Kicking Horse River, under the highway a second time and into the 991 metre (0.6 mile) tunnel in Cathedral Mountain. The train spirals to the right, emerging 17 metres (56 feet) higher and continues to the top of Kicking Horse Pass.

See them for yourself

There are two viewpoints where you can safely watch trains and learn more about the Spiral Tunnels and Kicking Horse Pass National Historic Site of Canada. On average, 25 to 30 trains pass through the Spiral Tunnels daily, though not on a regular schedule.

- From the viewpoint 7.4 km east of Field on the Trans-Canada Highway, you can see the Lower Spiral Tunnel in Mt. Ogden.

- The Upper Spiral Tunnel in Cathedral Mountain can be seen from the pull-off 2.3 km up the Yoho Valley Road.

Experience the past

- As you drive on the Trans-Canada Highway, near the Spiral Tunnels viewpoint, you’re following the path once known as the Big Hill. Imagine what it would be like over a hundred years ago, to be an engineer facing this hill in a steam train with heavy freight behind you.

- Date modified :