Culture and history

Auyuittuq National Park

Auyuittuq National Park and its surrounding region has a rich legacy of cultural resources that tell the story of human occupation of the area — a story that dates back thousands of years.

Pre-contact history

It is believed that the earliest people on Baffin Island were from the Pre-Dorset and Dorset cultures dating back more than 3,000 years from about 1700 B.C. to A.D. 1000. The ancestors of these people are believed to have originated in the Bering Strait region of Alaska prior to migrating across the Canadian Arctic and into Greenland, from west to east.

A second wave of migration from Alaska resulted in the arrival of Thule people into the eastern Arctic around the end of the 11th century, about 1,000 years ago. It is not known to what extent the Thule people displaced or intermixed with the Dorset people, but over time the Dorset culture disappeared, and by A.D. 1200 the Thule culture was predominant. Modern Inuit are direct descendants of the Thule people.

Within the park area, the earliest remains of human occupation are generally those of the Thule culture, although some evidence of the Dorset culture also exists. The Thule way of life was highly adapted to a coastal marine and tundra environment. With dogs, sleds, umiaqs (large skin boats), and kayaks, the Thule people were highly mobile hunters of land and sea animals. Seasonal activities were dictated by the abundance and distribution of the hunted species.

Seals, especially ringed seals, were their main source of food and were hunted year-round. Caribou were also hunted year-round, and the skins used to make clothing for the winter. Fish were important in the summer months, and in the spring ice fishing and waterfowl hunting added variety to their diet. Bowhead whales and narwhals were also prized and hunted, and there is some evidence that walruses were hunted as well.

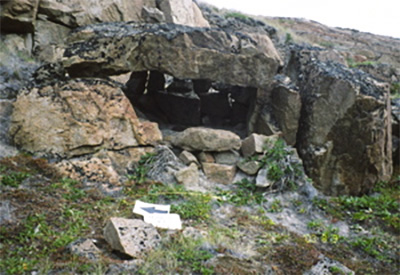

Thule people usually used the same winter settlements year after year. Early Thule winter houses were built with sod, stone, and whalebone. The roofs were built with whale ribs and covered with skins and sod. The inside of the dwelling would be slightly below ground level, with a tunnel from the outside leading in. The rear of the dwelling would contain a sleeping platform with small storage compartments underneath. Side platforms would hold the seal oil lamps and would serve as tables for cooking and drying clothes.

Over the centuries there were some variations in the Thule lifestyle in response to environmental conditions. For example, a cold climatic episode dubbed the "little ice age" occurred over a period of about 400 years, affecting the hunting patterns of the Thule people and forcing them to become more nomadic and to disperse. Despite the environmental changes, the Thule culture persisted until the period of earliest contact with Europeans, a period that also coincided with the end of the "little ice age". The transition from Thule to Inuit culture occurred between 1600 and 1850.

Post-contact history

Early contact period (1585 to the late 1800s)

Europeans began entering the region as early as 1585, although there are no records of actual contact during that time. John Davis, who arrived in 1585, was the first European to explore the Cumberland Peninsula region. According to expedition reports, the explorers saw no people although they did see signs of human habitation. William Baffin's 1616 voyage into Baffin Bay opened the door for increasing numbers of European whalers between Baffin Island and Greenland.

While some contact with European whalers may have occurred sooner, the first recorded contact between Europeans and Inuit occurred in 1839 when William Penny entered Cumberland Sound. By 1852, American whalers had established a winter camp in Cumberland Sound, and the British followed soon after.

With the advent of whaling in the area, Inuit culture began to change. Seasonal hunting continued, but patterns changed to accommodate the whaling season as many Inuit were employed by the whalers. Settlement patterns also changed as the whaling stations became a focal point for the availability and distribution of European goods.

The Twentieth century

By the early 1900s, whaling was no longer profitable, and most of the whaling stations closed. Inuit who had settled near the stations now had to move onto the land in search of food and furs for trade. They lived in small, semi-permanent camps, many of which were located in the same areas as the old Thule sites.

A trading post was established in Pangnirtung by the Hudson Bay Company in 1921. This was followed by an RCMP detachment in 1923, and an Anglican church in 1925. A hospital was opened in 1930. Many years later, the hospital closed when air travel made it cheaper to fly patients to Iqaluit. A nursing station remains in Pangnirtung today. School and government departments were opened in Pangnirtung in the early 1950s, and by the early 1960s most Inuit in the area had permanently relocated into the community.

North of the park, the community of Qikiqtarjuaq wasn't established until the early 1960s, prior to which Inuit of the Broughton Island region lived in semi-permanent camps on the land. The establishment of Qikiqtarjuaq was tied in with the construction of a DEW Line site in 1955.

- Date modified :