Ecological monitoring

Kluane National Park and Reserve

Parks Canada has a legal mandate to maintain or improve the ecological integrity of each national park. For Kluane National Park and Reserve this means ensuring the continuing health of its ecosystems – glaciers, icefields and fresh water, alpine tundra, and forests. Ecological monitoring tracks changes to ecosystem health over time.

Monitoring Framework | Ice and water | Forests | Tundra

Kluane Monitoring Framework

Park monitoring is not new: staff have counted Dall sheep since 1973, and moose since the 1980s. But in order to capture a fuller picture of ecological health, Kluane’s monitoring framework was created in 2008, following public meetings in Haines Junction and Burwash. It was revised in 2014.

Parks Canada is working with our partners, Champagne & Aishihik First Nations and Kluane First Nation, to re-envision how we monitor the land using both and Indigenous and western science lens.

Ecosystems

Ice and water 83% of park

Monitoring measures

Wood frogs

Each spring, when the ice melts from ponds in Kluane National Park and Reserve, staff put on their hip waders and head into the field to listen for the chorus of croaking frogs. Parks Canada monitors wood frogs (Tsʼäl in Southern Tutchone language) in Kluane by visiting the same 17 ponds each spring to listen for the mating call of male wood frogs.

Call surveys

Their characteristic croak tells us that frogs are present and to what extent. We also survey their egg masses and keep an eye out for these elusive frogs while at the ponds. If we consistently hear nothing at a pond where we used to hear calls, we know something is different. That’s why we also take water chemistry and environmental measurements to keep track of other potential sources of change.

Long term monitoring

Long-term monitoring of these durable yet sensitive amphibians gives us an indication of the overall health of freshwater ecosystems in Kluane. Since we started monitoring wood frogs in 2009, we’ve seen ponds dry up then come back. We’ve seen frog presence remain stable in some ponds while fluctuating in others. Continuing these surveys will certainly yield interesting observations and valuable information to help manage and protect Kluane’s freshwater ecosystems.

Kokanee salmon (Sachäl)

Kokanee salmon are found from California to Alaska. Kluane National Park and Reserve protects the most northern population of kokanee in Canada and is Canada's only national park with a naturally occurring population of kokanee salmon. Kluane's kokanee complete their entire life cycle in the fresh waters of the Kathleen Lake ecosystem.

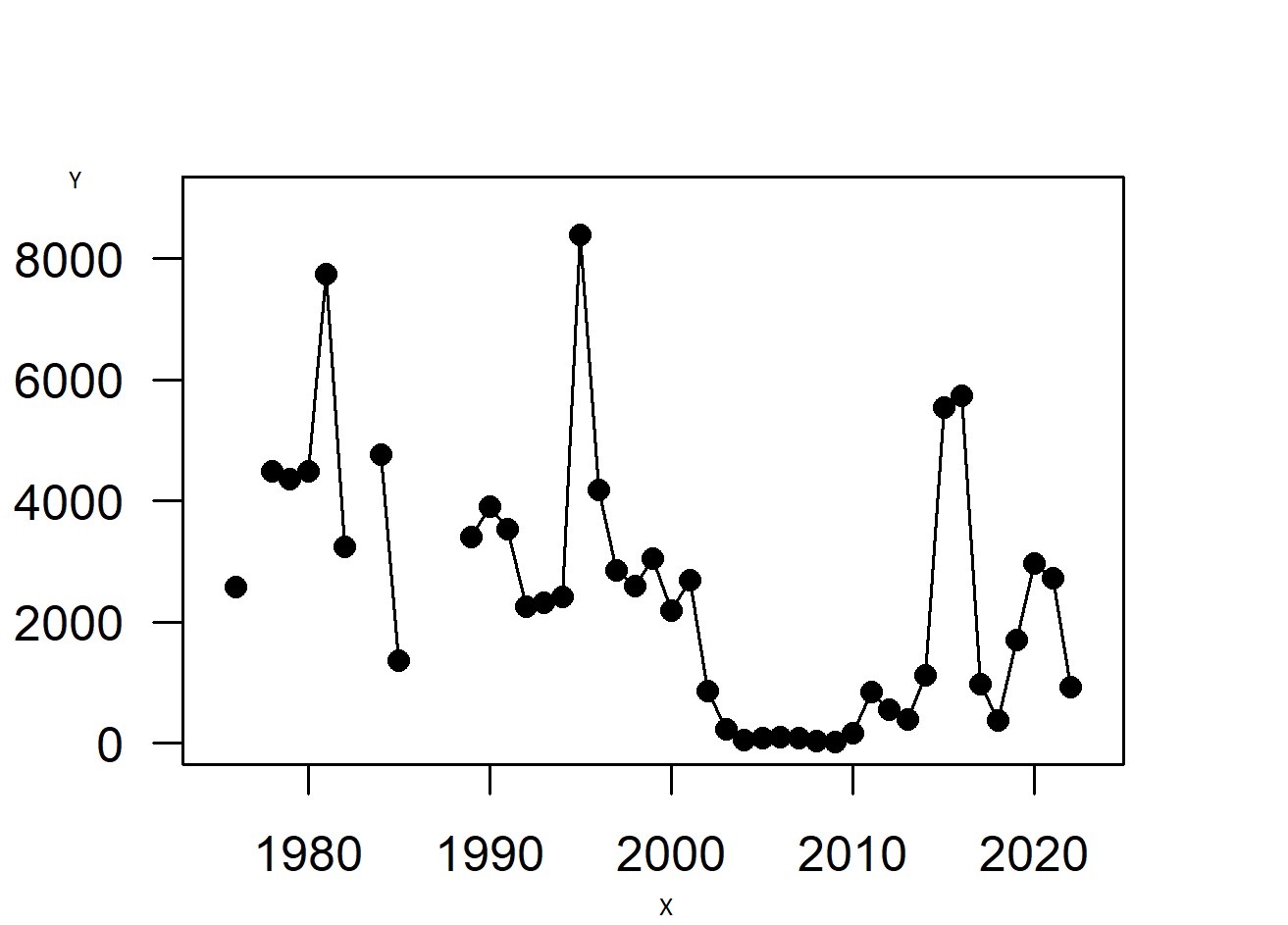

Y: Number of spawners

Dramatic Decline

The park has been monitoring kokanee salmon as they return to spawn in Sockeye Creek for over forty years. Historically the number of spawners has averaged 3660 fish but in the early 2000s the numbers dropped dramatically. Only 730 were counted in 2002, decreasing to an all-time low of 20 spawners in 2009.

After over a decade-long severe depression in population numbers, in both 2015 and 2016, we had incredible returns of around 5500 fish. This confirms that kokanee in the Park follow a boom and bust population cycle. We had been cautiously optimistic about the recovery but low numbers again in 2017 confirm the need for precautionary management. When the population is in a bust-phase of its cycle, it is at higher risk of local extinction.

In 2021, we saw around 3000 returning spawners to Sockeye Creek. These were the offspring of the exceptionally high number of spawners in 2015 and 2016. The below average returns from this boom in population highlights their vulnerability to other factors. In 2022 we saw approximately 1000 spawners return.

To protect the remaining population, the park has banned possession of kokanee by recreational anglers since 2004. The area around the spawning grounds is designated a Zone 1, Special Preservation Area, with no public access. Parks Canada and Champagne and Aishihik First Nation ask for the cooperation of all in not targeting kokanee.

Why did the decline happen?

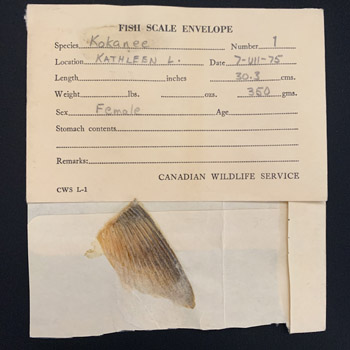

When wildlife populations go through a decline like the kokanee did from 2002 to 2014, concerns are raised for their genetic health. Researchers examined genetic variation pre- and post- crash using archival fish scale and fin samples. These samples were carefully stored but were largely forgotten until they were unearthed during an office move in 2013. DNA extraction techniques have advanced, and researchers were able to use new techniques to extract usable DNA from 40- and 50-year-old samples!

In their recently published work (A and B), researchers found that the current kokanee population does indeed have low genetic diversity. However, what was surprising was that it also had low genetic variation prior to the crash. This emphasizes the resilience of this population but also its vulnerability – it does not have a lot of genetic diversity to draw on in order to adapt to new threats. Their work also confirmed that the hatchery population in Whitehorse, which was founded from the Kluane National Park and Reserve population in the 1990s, is no longer genetically similar to the wild population. This means that hatchery stock is not a viable restoration option.

We continue to work on trying to tease out the drivers behind the large fluctuations in this population by monitoring streamflow, water temperature, angler harvest and lake trout, kokanee’s predator. This three-year project is supported by Parks Canada’s Conservation and Restoration (CoRe) funding.

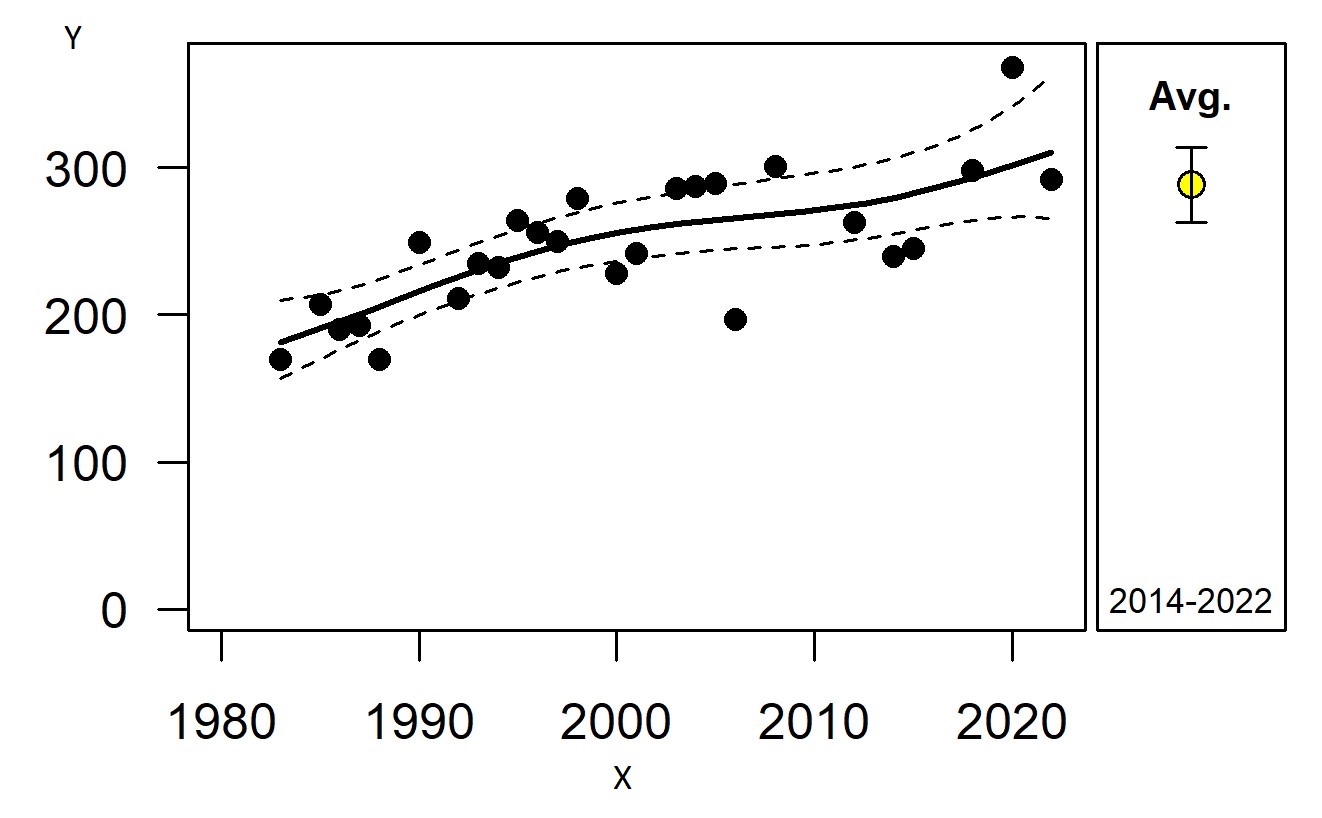

Lake trout

Lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush), known as Mbet in Southern Tutchone, are an important link in the aquatic food chain of large lakes in Kluane National Park and Reserve. To monitor the health of lake trout populations and predict the impacts of climatic changes to these populations, Parks Canada conducts netting surveys, angler surveys, fish sample analysis and lake temperature monitoring. Although our monitoring has a long-term focus, we have already observed some interesting findings.

Netting surveys

Since 2010, we have conducted netting surveys in 3 lakes (Kathleen, Mush and Bates). The method involves catching fish of different sizes and at different depths to get an index of the population size over time. The lake trout population on Kathleen Lake is currently considered healthy based on the fact that there has been no change in the amount of effort needed to catch fish.

Population demographics

It takes time for lake trout to grow in Kluane’s cold waters. Although age generally increases with length, this is not a hard and fast rule. For example, the oldest lake trout caught was 39 years old but had a fork length of only 396 mm, whereas the longest fish caught had a fork length of 845 mm and was 26 years old.

Angling surveys

The most recent angler survey in the park was conducted for Kathleen Lake in 2015. We look at many things when doing these surveys to get a good idea of the impacts of angling on fish populations. One interesting point of note was the lack of concern that anglers had towards invasive aquatic species – 30% of respondents were unconcerned or neutral about the threat of invasive species. This is especially concerning considering 38% of anglers came from outside the Yukon, some as far away as Lake Superior or the southern U.S. We need to raise awareness on invasive aquatic species.

Water quality

Water sampling

Parks Canada staff have been collecting monthly water samples from the Dezadeash River since 1993. This is part of a long partnership with the Water Quality Monitoring Network of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Water quality index

Water quality is assessed using the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment Water Quality Index for the protection of aquatic life. Water quality for the Dezadeash River has remained in a state of good ecological integrity with a stable trend.

Glacier area

“We are seeing glacier changes that shouldn’t be observable on human timescales.”

Then and now

James J. McArthur was a surveyor and mountaineer who surveyed near the Kaskawulsh Glacier around 1900. Glass negatives of his historic photos were found by chance in a pile of negatives of the Rocky Mountains. The site where he took the photo of the Kaskwulsh in 1900 was revisited in 2012 and 2018. The retake of his photo in 2018 reveals the dramatic retreat of the Kaskawulsh Glacier, over 1 km in just over 50 years. The stream capture event of 2016 is also evident. See more evidence of landscape change in the Park through the retakes of historic photos at Mountain Legacy Project.

Glacial change

Glaciers and large icefields cover almost 80% of Kluane National Park and Reserve. In the last 50 years, the area glaciated has decreased by 20% and over 230 small glaciers have disappeared due to climate change. Understanding the dynamics behind this change and the resulting impacts to the Park is a large challenge. Parks Canada relies on the work of independent researchers to further our understanding.

Learn more

Forests 10% of park

Monitoring measures

Moose

Parks Canada has monitored Känäy (moose -- Alces alces) populations in the Park since 1981. Two populations are regularly surveyed in early winter via helicopter; one in the Auriol Range and one in the Shär Nuh Chù’ / Duke River area.

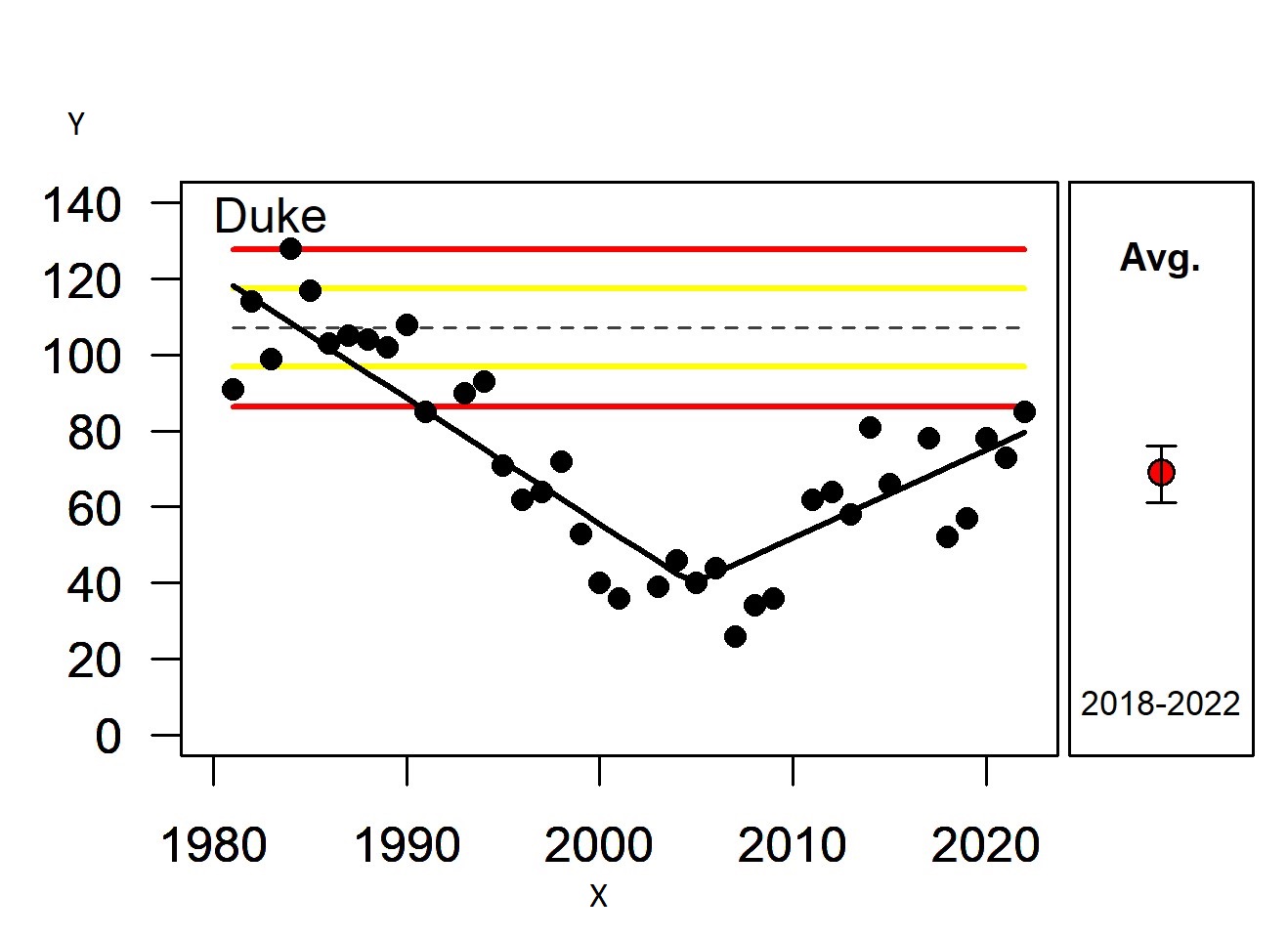

X = Year, Y = Moose Count

The Auriol population in the southern half of the Park has been slowly increasing since the early-1980s.

X = Year, Y = Moose Count

The Duke population in the northern half of the Park steadily declined between the early-1980s and mid-2000s. A 2011 survey by Parks Canada, the Yukon Government and the Kluane First Nation confirmed that moose numbers were low both inside and outside the park. Since then, the Duke population has been recovering but numbers remain low.

Parks Canada is working with partners and local communities to explore potential causes for the Duke decline and to find ways of ensuring moose populations in the Park remain in good health.

Songbirds

We can learn a lot about the overall health of Kluane's forests from our songbirds. Parks Canada has been monitoring breeding songbirds on the Auriol Trail since 2009.

Early birds gets the worm!

Each bird survey starts early in the morning, before 4 am, in June and identifies songbirds heard or seen at 12 different locations along the trail. We use special omni-directional microphones as shown in the photo to record birds at each site. That way we can re-listen to bird songs in the office to confirm our identification of species.

Area burned

Fire cycle

Wildfires were a key natural disturbance in the boreal forest in Kluane National Park and Reserve whether ignited by lightning strikes or by First Nations to modify habitat. Mean fire intervals ranged from ~200 years in the south portion of the Park to 400 to 500 years in the north.

Fire suppression

Since policies of fire suppression began around 1950, only 380 hectares through 19 small fires have burned in the Park. If wildfires were to burn as they did historically, approximately 107, 275 ha should have burned in the last 160 years. Only about 31,000 ha have actually burned, representing a 72% deficit in the Park overall. Thus, the rating of poor ecological condition due to the lack of recent fires in the Park.

Fire history research from the 1980s showed that wildfires were historically a natural process in the boreal forest, whether started by lightning or from First Nations’ activities. For more than half a century, fire has been actively excluded from this area through fire suppression and the forced removal of First Nations’ cultural practices.

This lack of fire on the landscape may have contributed to unintended consequences, like a build up of forest matter and changes in overall tree age and type. With this project, our hope is to restore balance to our forests and increase their ability to withstand and recover from past and future changes.

Further fire history research is underway and project partners are identifying possible sites for active management, like prescribed fire, within KNPR. Final decisions on sites and actions will be carried out based on the shared goals of Champagne & Aishihik First Nations, Kluane First Nation, and Parks Canada.

Forest composition and structure

An outbreak of spruce bark beetle caused unprecedented levels of mortality of white spruce in southwest Yukon and Alaska from 1995 to the mid-2000s. Most of the spruce - dominated forest (82%) in Kluane National Park and Reserve was affected (49,000 ha). Within the attacked forest, on average almost half of the mature spruce trees were killed (44%). In order to understand the resilience of the forest to this novel disturbance, Parks Canada set up 50 permanent sample plots to monitor every 10 years.

Forest composition

Is the forest in Kluane National Park and Reserve becoming more dominated by deciduous trees like trembling aspen in the overstory? What about in the understory?

Since the spruce bark beetle outbreak, the relative dominance of deciduous trees in the overstory has significantly increased in the southern but not the northern area of the Park. There is significantly more willow than tall regenerating spruce which could inhibit tree regeneration in the understory.

As of 2015, the forest remained spruce dominated with a deciduous component within the range of natural variability.

Forest structure

Will the structure of the forests recover to similar conditions prior to the spruce bark beetle outbreak?

Parks Canada is monitoring the number of live spruce trees both mature and regenerating and as well as the volume of downed dead wood. As of 2015, the forest currently does not have not enough live trees in the canopy, nor in tree regeneration in the understory relative to conditions prior to the beetle outbreak. We are paying particular attention to the health of regenerating trees as we found widespread damage by snowshoe hares feeding on spruce seedlings.

Tundra 7% of park

Monitoring measures

Dall's sheep

Dall’s sheep are found in mountain ranges from northern British Columbia to Alaska. They are an iconic Kluane species and highly valued by Kluane First Nation and Champagne and Aishihik First Nations. Along with mountain goats, they are considered one of the bellwether, or indicator, species of climate change in alpine ecosystems.

Kluane populations

Since 1977, Parks Canada has monitored four different Dall’s sheep populations in the park. As of 2023, the Thechàl Dhâl’ (Sheep Mountain) population has been surveyed 42 times, creating one of the most consistent and longest running data sets of any population across the species range. The other three populations (Auriol, Vulcan, and Donjek) have been surveyed more than 20 times each since 1977.

In 2023, adult sheep numbers were below historic averages in all four populations. In the Thechàl Dhâl’ population, declining numbers have led to some of the lowest counts of sheep on record, partly driven by multiple years of low lamb numbers and poor recruitment ratios. This ratio—the number of lambs per 100 ewes in early summer—is important for predicting how many lambs might become breeding adults in the future. In 2021 and 2022, poor lamb recruitment was observed across the region and Alaska suggesting a widespread climatic factor at play, such as prolonged winter conditions into the lambing period. Parks Canada is actively working with partners on reducing non-climatic stressors, such as disturbance from dogs and mortalities from collisions with vehicles, to help sheep increase their resilience to climate change.

Highway collisions

Parks Canada is working with Yukon Government Highways and Environment Department and Kluane First Nation to reduce collisions between Dall’s sheep and vehicles on the Alaska Highway. Please slow down around Thechàl Dhâl (Sheep Mountain).

Learn more

Mountain goats

Approximately 600 adult mountain goats are found in Kluane National Park and Reserve - almost 40% of the entire population in Yukon. Along with Dall’s sheep, they are considered one of the bellweather species of climate change in alpine ecosystems.

Helicopter surveys

To determine the health of the population over time, Parks Canada has conducted helicopter surveys of mountain goats around Goatherd Mountain since 1977. The number of mountain goats counted is affected by the temperature on the day of the survey. Once temperature is accounted for, there is no significant trend in either adult goats or kid counts. This population is considered healthy as of the last survey in 2018.

Alpine vegetation

To monitor change in alpine vegetation, Parks Canada has established permanent monitoring plots in seven different alpine area.

Growing season

At each, we are measuring the length of the growing season using dataloggers which record levels of sunlight and temperature on the hour. This will be used to validate satellite derived indices of growing season across the landscape.

Vegetation change

We are also measuring plant diversity, the height of shrub cover and permafrost. These plots were first set up in 2011 and the resulting stories of change will take some time to tell.

- Date modified :