Part A: The State of Parks Canada Natural Heritage Places Establishment, Cultural Heritage Programs and Other Heritage Programs

National Park Establishment

Context

Since it was established as the world’s first national park service in 1911, Parks Canada has been entrusted to protect an increasing number of natural areas within a system of national parks that represents each of Canada’s 39 natural regions. The area of land currently protected in Canada’s 46 national parks and reserves stands at 328,198 square kilometres covering representative samples of the wide variety of natural landscapes that characterize Canada.

The need to protect a representative collection of examples of Canada’s land and marine natural regions, was acknowledged by Parliament when it passed the Parks Canada Agency Act in 1998. Parliament directed Parks Canada to ensure that a long-term plan be in place for establishing a system of national parks, and made the Agency responsible for negotiating and recommending the establishment of new protected places.

The establishment of a national park includes a series of steps starting with the identification and selection of a potential park, followed by a feasibility assessment that includes public consultations. If governments agree to proceed, national park establishment agreements are negotiated with the relevant governments and implicated Indigenous organizations. The final step is to formally protect the new park under the Canada National Parks Act.

State of National Park Establishment

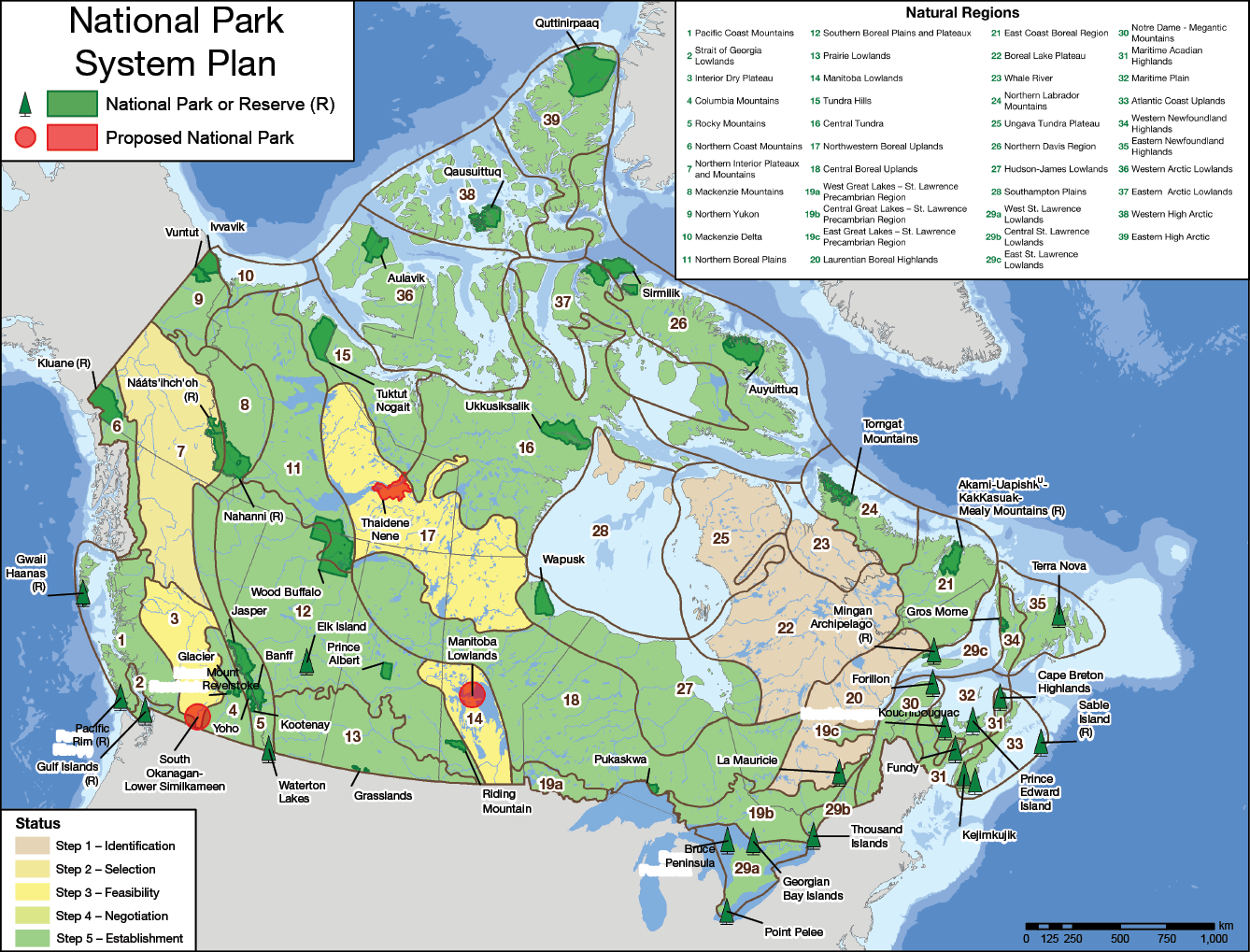

The government is committed to protecting our natural heritage through the expansion of the system of national parks. Expanding Canada’s network of protected areas provides a “natural solution” for climate change by conserving biodiversity; protecting ecosystem services; connecting landscapes, capturing and storing carbon; building knowledge and understanding; and inspiring people. To date, 30 of 39 of Canada’s natural regions are represented by 46 national parks and national park reserves (Figure 1). Since the last report in 2011, four new national parks and reserves have been added to the system, increasing the number of represented natural regions by two and adding over 27,400 square kilometres. National park establishment agreements were concluded and signed for Akami-Uapishkᵁ-KakKasuak-Mealy Mountains (Labrador), Qausuittuq (Nunavut), Nááts’ihch’oh (Northwest Territories) and Sable Island (Nova Scotia). Parliament subsequently passed legislation to formally protect Sable Island, Nááts’ihch’oh, and Qausuittuq under the Canada National Parks Act.

Consultations and negotiations continued on the Thaidene Nëné proposal, and work with Indigenous groups continued on the Manitoba Lowlands proposal. However, the Government of British Columbia indicated in 2011 that it was not prepared at this time to continue with the feasibility assessment for a national park reserve in the South Okanagan–Lower Similkameen region.

Actions

Akami-Uapishkᵁ-KakKasuak-Mealy Mountains National Park Reserve (Newfoundland and Labrador): In 2015, three historic documents were signed formalizing the commitment to establish a national park reserve in the Mealy Mountains of Labrador. A Memorandum of Agreement with the provincial government and a Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement with the Innu Nation were signed in July 2015. This was followed by a Shared Understanding Agreement with the NunatukKavut Community Council signed in September 2015. Concurrently, negotiation of a Park Impacts and Benefits Agreement with the Nunatsiavut Government commenced.

Together, these agreements set the stage for the formal establishment and protection of Akami-Uapishkᵁ-KakKasuak-Mealy Mountains National Park Reserve, a 10,700-square-kilometre national park reserve that will represent the East Coast Boreal Natural Region of the national park system. Once the agreement with the Nunatsiavut Government is achieved, protection of this area under the legislation will be the final step to complete the park establishment.

Qausuittuq National Park (Nunavut): In January 2015, the Government of Canada and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association signed an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement, making a formal commitment to cooperatively protect and present an 11,008-square-kilometre national park on northern Bathurst Island. On September 1, 2015, the park was formally protected under the Canada National Parks Act, thereby representing the Western High Arctic Natural Region of the national park system.

Nááts’ihch’oh (Northwest Territories): Nááts’ihch’oh was established pursuant to an Impact and Benefit Plan that was negotiated and signed in 2012 by the Sahtu Dene and Métis and the Government of Canada. The 4,894-square-kilometre national park reserve was subsequently protected under the Canada National Parks Act in 2014. Located in the northern part of the South Nahanni River watershed, the park reserve is adjacent to the northwest of the existing Nahanni National Park Reserve. The two parks combined protect 86 percent of the South Nahanni River watershed.

Sable Island (Nova Scotia): The governments of Canada and Nova Scotia signed a national park reserve establishment agreement in 2011 to protect Sable Island. The island was formally protected under the Canada National Parks Act in 2013. The bill establishing the park prohibited drilling from the surface of Sable Island as well as within a 200-square-kilometre buffer zone that encircles the island. The creation of the park was facilitated by several energy companies that voluntarily relinquished their drilling rights.

Thaidene Nëné (Northwest Territories–East Arm of Great Slave Lake): There has been significant progress on this national park proposal since the last report. Separate national park establishment agreements in progress were initialled by the Government of Canada, the Łutsel K’e Dene First Nation and the Northwest Territories Métis Nation. Both agreements require confirmation of a final boundary for the park and financial elements. To that end, in July 2015, the Government of Canada announced a 14,000-square-kilometre boundary for consultation. Once established, this park will represent the Northwestern Boreal Uplands Natural Region of the national park system.

Key Issues and Focus for the Future

Parks Canada cannot unilaterally create or expand national parks. It requires the support and collaboration of provincial and territorial governments as well as Indigenous governments, organizations and communities. In order to protect an area under the Canada National Parks Act, the administration and control of such lands, including subsurface, must be transferred to Parks Canada.

Parks Canada works to consult and accommodate Indigenous peoples implicated by proposed new national parks. The focus is on identifying and addressing any potential negative impacts such proposals may have, to put in place collaborative working relationships, and to ensure benefits accrue to Indigenous peoples from the proposed protected area.

Parks Canada needs to take the necessary time and measures to secure the support of other levels of government including Indigenous, as well as implicated Indigenous peoples. Here are some possible means to improve the process to establish new national parks based on recent experience:

- Political dialogue between federal and provincial/territorial governments and Indigenous leaders from the outset, and on an ongoing basis, that establishes some basic parameters and timing around decisions required to establish a new national park;

- Undertaking environmental scans and pre-feasibility work to identify, very early in the process, the systemic and regional issues that may affect an establishment project, and to identify the substantive issues that Parks Canada and other partners would need to address, could help position Parks Canada to address these issues from the start;

- Engage Indigenous peoples in the identification and establishment process as early as possible and find means to formalize and maintain that level of engagement. Taking the time to confirm that Parks Canada and Indigenous communities have a shared vision for the land and in what they want to achieve can greatly assist a project. Providing financial support to Indigenous communities so that they can meaningfully participate in feasibility assessments, consultations and negotiations has proven to be a critical element in Parks Canada’s past successes; and

- Improved capacity for public consultation, communications and engagement over the life of a project can facilitate building local understanding and support for establishment initiatives. While Parks Canada will not be able to answer every issue raised in public and stakeholder consultation, ensuring prompt responses to land use issues that are raised can work to somewhat alleviate the concerns of local residents.

Figure 1: National Park System Plan

[text version]

National Marine Conservation Areas Establishment

Context

Canada has the world’s longest coastline covering over 243,000 kilometres along the Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific oceans, with an area of more than 5.5 million square kilometres of ocean waters and the world’s second largest continental shelf. Canada also shares jurisdiction over the Great Lakes, the world’s largest freshwater system. These marine environments are fundamental to the social, cultural and economic well-being of Canadians.

Parliament mandated Parks Canada to establish a system of national marine conservation areas (NMCAs) representative of the diversity of Canada’s 29 oceanic and Great Lakes marine regions. Parks Canada’s role is to ensure the protection and ecologically sustainable use of these NMCAs, facilitate unique experiences and an appreciation of marine heritage, and engage Canadians in the management of NMCAs.

The establishment of an NMCA includes a series of steps starting with the identification and selection of a potential site followed by a feasibility assessment with public consultations. If governments agree to proceed, an NMCA establishment agreement is negotiated with the relevant governments and implicated Indigenous organizations. The final step includes the development of an interim management plan and formal establishment under the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act (CNMCA Act).

State of National Marine Conservation Areas

The Government is committed to protecting our natural heritage through the expansion of Canada’s system of national marine conservation areas. Healthy coastal habitats, such as salt marshes and seagrass meadows, play many important roles including the storage of carbon. The storage of this “Blue Carbon” serves to mitigate the release of greenhouse gases that cause climate change. Parks Canada is a federal government leader in the investigation of Blue Carbon in Canada and is working with the USA and Mexico through the Commission for Environmental Cooperation. Currently, we are working to better understand the value of Blue Carbon habitats in global carbon storage.

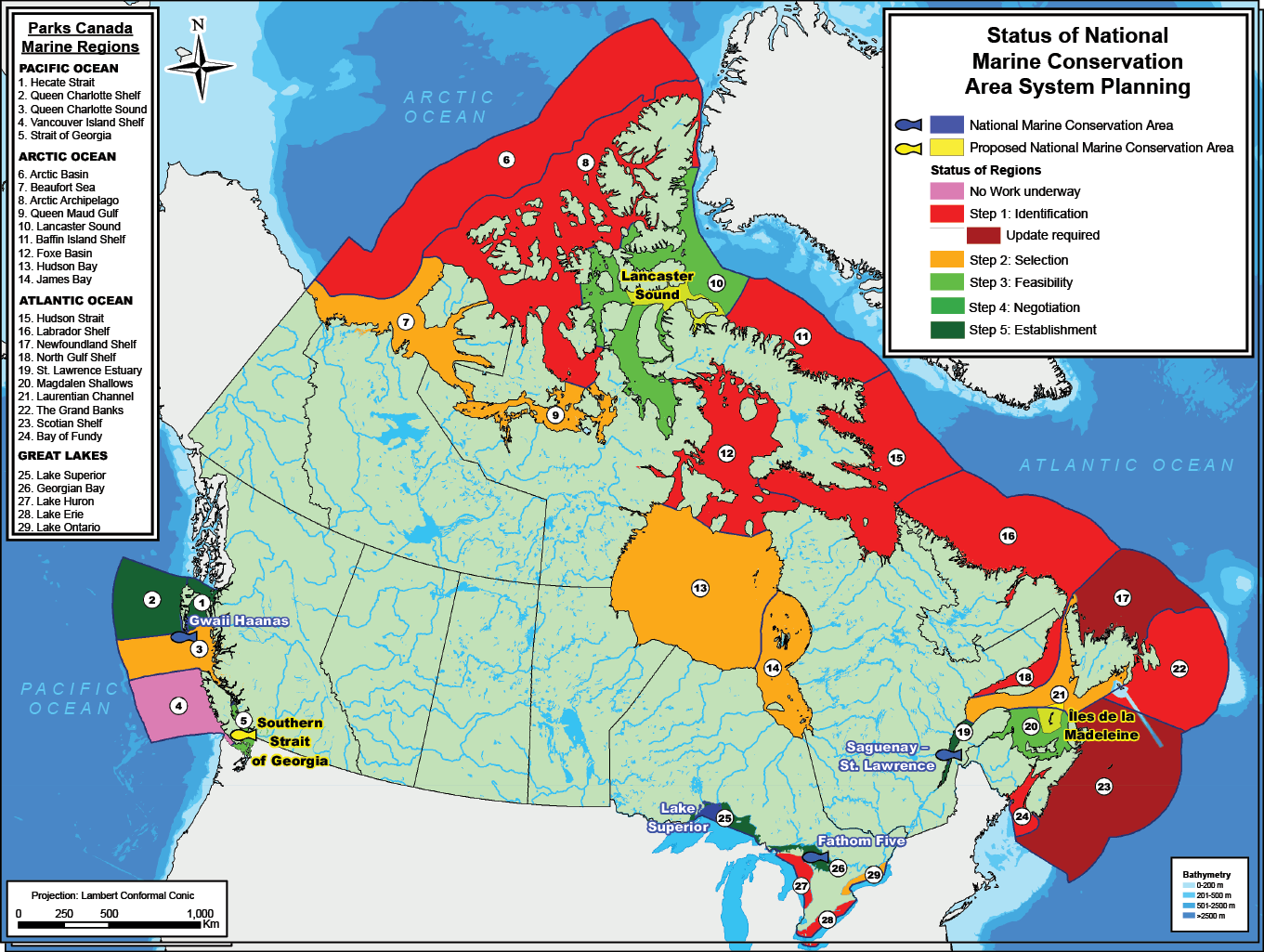

As of March 31, 2016, the national marine conservation area system was 17 percent complete. The system includes four areas representing five of the 29 marine regions and protecting 15,740 square kilometres, an increase of six percent over the previous reporting period.

These areas are Fathom Five National Marine Park (Ontario), which protects part of Canada’s maritime history, including twenty-one wrecks of sail and steam vessels from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century; Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park (Quebec), managed jointly with Quebec, which protects important habitat for beluga whales; Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area (Ontario), one of the largest freshwater protected areas in the world; and Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site (British Columbia), which represents two marine regions. In combination with the adjacent national park reserve, Gwaii Haanas NMCA and Haida Heritage Site is the only place in the world to be protected from the mountaintops to the deep sea.

Although work has continued on the establishment of additional sites, no new NMCAs were created during the reporting period.

Actions

A significant achievement during this period under review was the passage of legislation in 2015 that will enable the formal establishment of Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area under the CNMCA Act, which was amended to confirm Ontario’s continuing role in the taking of water for municipal and other small scale uses. The Government of Ontario has begun the work to transfer the NMCA’s lake bed and islands to Canada. Once this process is complete, the NMCA will be formally established under the Act.

Parks Canada continued also to make progress on the feasibility assessments for three NMCA proposals in unrepresented marine regions.

- Southern Strait of Georgia (British Columbia): In October 2011, the governments of Canada and British Columbia announced a boundary for consultation for the proposed Southern Strait of Georgia National Marine Conservation Area Reserve. This was followed by consultations with Indigenous stakeholders and municipal governments, as well as the development of a concept for the NMCA reserve, which would help to define the project better and assist with consultations.

- Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Quebec): Parks Canada continued to work with the Government of Quebec to develop an approach for a marine protected area in the waters adjacent to the islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

- Lancaster Sound (Nunavut): Parks Canada, the Government of Nunavut and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association consulted with local communities, stakeholders and government departments, working towards the completion of the feasibility assessment for this area.

Consistent with the mandate to represent each of the 29 marine regions, Parks Canada has continued to work to identify representative areas within each region as potential for NMCA candidates. By March 31, 2016, 28 marine regions had undergone a study to determine these areas. The last marine region will be examined in the near future. As a result, the general plan for the NMCA system is emerging.

The map (Figure 2) provides an overview of the status of planning for the NMCA system.

Key Issues and Focus for the Future

Creating new national marine conservation areas takes time. These areas are established in a complex jurisdictional environment with numerous federal government departments, provincial and territorial governments and Indigenous peoples having important roles to play in the protection and management of Canada’s marine waters. With the requirement for national marine conservation areas to balance protection and ecologically sustainable use, this also brings in a greater range of stakeholders to consider, and work with. Bringing all of these elements together and moving forward in a harmonious and positive way requires time and respectful discourse.

In addition, many Canadians still do not fully appreciate the important role that marine protected areas in general—and national marine conservation areas in particular—can play in safeguarding our marine environments and ensuring their sustainability into the future. Parks Canada, in collaboration with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and provincial and territorial governments, is working to improve that understanding.

NMCAs will make an important contribution to the achievement of Canada’s international marine protected area commitments of 10 percent by 2020, as well as to the government’s goal of protecting 5 percent of Canada’s marine and coastal waters by 2017. To that end, Parks Canada’s focus will be on establishing an NMCA in Lancaster Sound, completing feasibility assessments and negotiations for the two existing proposals (Southern Strait of Georgia and Îles-de-la-Madeleine) and initiating new NMCA proposals.

Figure 2: Status of National Marine Conservation Areas

[text version]

Rouge National Urban Park Establishment

Context

Rouge National Urban Park is a new type of protected area within the Parks Canada family of protected areas, and a Canadian first, specially created because of its urban setting. It is a great example of a protected “cultural landscape” where expanses of natural ecosystems are intertwined with agricultural lands that speak to generations of sustainable farming activities. As a federally designated protected area with its own legislation, Canada’s first national urban park celebrates the diversity of Rouge’s natural and cultural landscapes and the presence of a vibrant farming community, and offers opportunities for a broad diversity of Canadians to connect with the park through events, recreational and learning activities, stewardship, volunteerism and citizen engagement.

Located within the Greater Toronto Area, Canada’s most populated and culturally diverse metropolitan centre, Rouge National Urban Park fulfils the goal of community leaders and visionaries of creating a park connecting Lake Ontario to the Oak Ridges Moraine. Once fully established, Rouge National Urban Park will be the largest urban park in North America.

State of Rouge National Urban Park

Since the creation of Rouge National Urban Park was first announced in 2011, Parks Canada has consulted with over 20,000 Canadians and worked closely with Indigenous peoples, all levels of government, community groups, environmental NGOs, farmers, residents, universities and many other groups on the park’s planning and establishment.

The Rouge National Urban Park Act came into force on May 15, 2015, formally establishing the park. In 2015, Transport Canada transferred 19.1 square kilometres to Parks Canada—the first lands for Rouge National Urban Park. Parks Canada continues to work with all levels of government on the land assembly for the park with additional land transfers expected to occur in 2017. Once land assembly for the national urban park is completed, the park will cover a 79.1-square-kilometre area.

In 2016, the Government of Canada tabled Bill C-18 to amend the Act and strengthen the protection of Rouge’s important ecosystems and heritage as well as ensuring that ecological integrity becomes the first priority in the park’s management. The amendments also provide greater certainty for park farmers, who will be able to continue carrying on agricultural activities within the park as a primary source of locally grown food to the Greater Toronto Area. The Agency has also established a First Nation Advisory Circle with ten Indigenous groups having historical ties to the park. It will guide the establishment and management of the park and its operations.

Actions

In 2014, a formal public engagement process was undertaken on the draft management plan for Rouge National Urban Park.

Since 2015, Parks Canada has been working collaboratively with municipalities, park farmers, schools and environmental groups to improve the health of Rouge National Urban Park, completing thirty ecosystem restoration and farmland enhancement projects. Leading-edge science is also contributing to species at risk recovery, ecological connectivity, invasive species control and cultural resource conservation throughout the park. Parks Canada will also develop a full suite of specific monitoring, assessment and reporting tools.

In 2015, Parks Canada opened its first visitor facilities in Rouge. The park serves as a gateway to Canada’s network of protected heritage areas and also aims to become Canada’s premiere “learn to” park.

Key Issues and Focus for the Future

Parks Canada will focus on conservation, orientation, education, new and upgraded camping facilities, and a comprehensive trail system connecting Lake Ontario with the Oak Ridges Moraine. Parks Canada will raise awareness and appreciation of the long history of farming in Rouge National Urban Park, from Indigenous people’s traditions over millennia, to the Mennonite farms of the 19th and 20th centuries to today’s modern farms.

National Historic Sites and Cultural Heritage

National Historic Sites and National Program of Historical Commemoration

Context

Created in 1919, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC) provides advice to the Minister responsible for Parks Canada on the designation of places, persons and events that have marked and shaped Canada. Every year, new subjects of potential national historic significance are submitted to the HSMBC for consideration. The participation of the public in the identification of these subjects and in their commemoration is a fundamental element of the program. The vast majority of submissions to the HSMBC originate from Canadian individuals and groups.

Designations of national historic sites, persons and events are usually commemorated with a bronze plaque that describes the historical significance of the subject. The plaque is installed in a location that is closely related to the designated subject and accessible to the public. The plaque unveiling ceremony is the culmination of the designation process and an opportunity for Canadians to enjoy and celebrate their history.

Parks Canada supports the HSMBC in its advisory role with secretariat services, historical and archaeological research, policy advice, media relations, planning of plaque unveiling ceremonies, and plaque installation and maintenance.

State of National Historic Sites and the National Program of Historical Commemoration

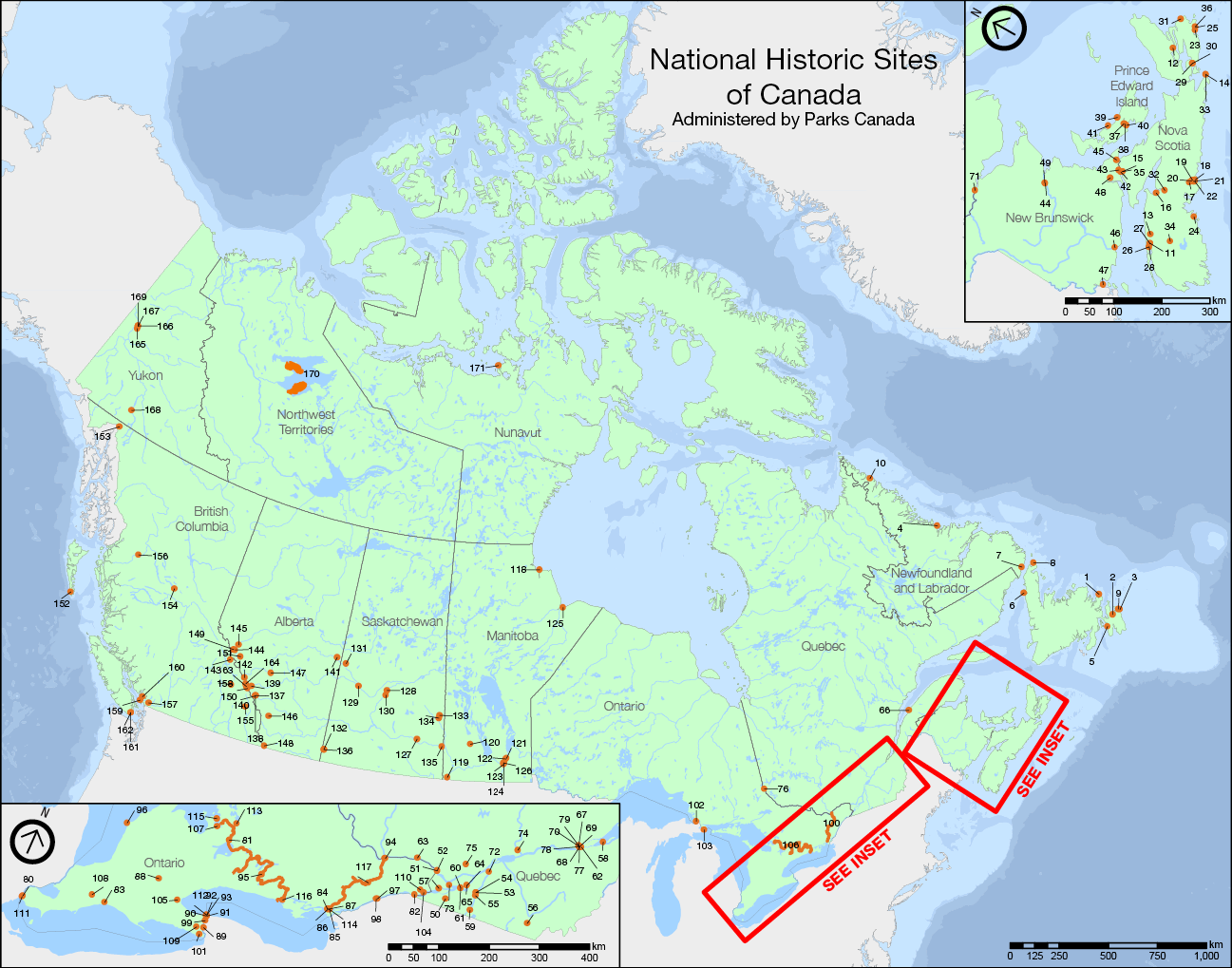

To date, the Government of Canada has designated 979 national historic sites—of which 171 are administered by Parks Canada (Figure 3)—along with 690 national historic persons and 475 national historic events.

From 2000 to 2011, Parks Canada made significant investments to generate new nominations related to three underrepresented areas in the National Program of Historical Commemoration: Indigenous peoples, women, and ethnocultural communities. From 2011 to 2016, the Government of Canada approved 66 new national designations that speak to these underrepresented areas.

In early September 2014, an expedition led by Parks Canada discovered the wreck of HMS Erebus in Nunavut. This historical accomplishment resulted in the establishment and the protection of the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site by adding the site to the Schedule of the National Historic Sites of Canada Order under the Canada National Parks Act. This new site became the first national historic site managed by Parks Canada in Nunavut.

Over the last five years, with the support of Parks Canada, the HSMBC reviewed approximately 130 subjects nominated for national historic designation. These evaluations resulted in notable designations, such as Margaret Laurence National Historic Person, the Komagata Maru Incident of 1914 National Historic Event, and T’äw Tà’är National Historic Site of Canada. Moreover, a cultural landscape under Parks Canada’s administration was designated, Beausoleil Island National Historic Site, which underscores the links between nature and culture for Indigenous communities.

Between 2011 and 2016, Parks Canada held plaque unveiling ceremonies for 78 designations in communities across the country, including the Asahi Baseball Team in Vancouver, British Columbia, the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–1918 in Sachs Harbour, Northwest Territories, Harriet Tubman in St. Catharines, Ontario, and the Crow’s Nest Officers’ Club in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. Many of the plaques unveiled over the last five years also coincided with celebrations of significant milestones, such as the centennial of the Grey Cup, the centennial of the creation of the Dominion Parks Branch, and the 75 anniversary of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet.

Key Issues and Focus for the Future

There is a significant number of designations under the National Program of Historical Commemoration that have yet to be commemorated by means of a bronze plaque. In support of the HSMBC and the Minister, Parks Canada is investing resources and undertaking efforts to commemorate all existing designations over the next few years.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action # 79 recommended, among other things, that the National Program of Historical Commemoration be reviewed to integrate Indigenous histories, heritage values, and memory practices. In the spirit of reconciliation, Parks Canada will work with Indigenous communities to expand the presentation and commemoration of the histories and cultures of Indigenous peoples.

Parks Canada is working on innovative approaches to improve how history is presented at heritage places across the country with the goal of responding to demographic shifts in the population and modernizing how Canadians—particularly new Canadians, youth, and urban Canadians—make meaningful connections with history. For example, Stories of Canada aims to encompass best practices in communicating compelling stories to capture the imagination of Canadians and to fully integrate Indigenous perspectives and voices into stories presented at Canada’s heritage places.

Cultural Heritage Protection and Conservation Programs

In addition to designations of sites, people and events of national significance, Parks Canada is responsible for eight heritage protection programs. These support and enhance the commemoration and protection of important cultural and natural heritage resources across Canada in all jurisdictions.

1) Heritage Lighthouses

The Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act came into force on May 29, 2010. The Act is designed to identify federally owned heritage lighthouses and to protect and conserve their heritage character. The Act establishes conservation and maintenance standards for federal custodians of heritage lighthouses. It also requires that the heritage character of a lighthouse be protected upon its sale or transfer out of the federal portfolio. Heritage lighthouses are designated by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada (the Minister of Environment and Climate Change) on the advice of the HSMBC. Parks Canada supports the Board in its advisory role to the Minister.

Canadians nominated 349 lighthouses for designation during a two-year nomination period that ended May 29, 2012. During the past five years, 76 heritage lighthouses were designated, consisting of 42 that will be managed by federal custodians and 34 that are surplus to the operational requirements of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. These surplus lighthouses are therefore destined to be protected and conserved by new, non-federal owners, primarily other levels of government and community-based organizations.

More communities wish to acquire and protect surplus historic lighthouses and, as such, are interested in having them designated as heritage lighthouses under the Act. Negotiations are ongoing between the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada and other levels of government and community-based organizations, which are developing sustainable, long-term business plans for local lighthouses. Once these negotiations are concluded, these historic lighthouses will become eligible for designation.

2) Heritage Railway Stations

The Heritage Railway Stations Protection Act (HRSPA) outlines the procedure through which stations are designated as heritage railway stations and provides a clear process to review and approve proposed changes or the sale of designated stations. Based on the advice of the HSMBC, the Minister responsible for Parks Canada designates heritage railway stations. Any proposal to sell or alter a designated station must be recommended by the Minister to the Governor in Council for approval.

Since 1990, 164Footnote 1 heritage railway stations have been designated under the HRSPA. As of March 31, 2016, 75 were still owned by federally regulated railway companies and fell under the protection of the Act, including such notable ones as Union Station in Winnipeg, Gare du Palais in Québec, and the VIA Rail Station in Halifax. The others have been sold to new owners who have committed to protect and conserve their heritage character.

Over the last five years, Parks Canada provided program and conservation advice to railway companies for over 50 interventions at more than 30 stations. Parks Canada will continue to work closely with heritage railway station owners and communities to promote effective conservation and protection of these landmarks.

3) National Program for the Gravesites of Canadian Prime Ministers

This program was created in 1999 to ensure that the gravesites of prime ministers were conserved and recognized in a respectful and dignified manner. It involves the preparation of conservation plans for each of the gravesites, installation of a Canadian flag and information panel on the life and accomplishments of the prime minister, and the organization of a commemoration ceremony in the prime minister’s honour.

To date, the gravesites of 15 prime ministers have been commemorated through the program. In 2011, each gravesite received a formal inspection by a conservation specialist. All were found to be in good or fair condition. Since then, major conservation challenges identified through those assessments have been addressed. Formal inspections are underway in 2016.

4) Canadian Heritage Rivers

The Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) is Canada’s national heritage river program—a cooperative federal-provincial-territorial program led by Parks Canada to recognize, protect and manage rivers having outstanding natural, cultural and recreational value. Parks Canada’s responsibility is set out in the Parks Canada Agency Act.

The CHRS is the world’s largest heritage river program, making Canada a leader in the identification of “river cultural landscapes” and in celebrating the cultural, natural, and recreational roles rivers play in many communities and for Indigenous peoples. Forty-two rivers have been nominated, spanning almost 12,000 kilometres. Thirty-eight of these have been designated, meaning that plans have been put in place to conserve and present their heritage value.

In the past five years, the South Saskatchewan and Saskatchewan rivers (Saskatchewan) were nominated to the CHRS and the Saint John River (New Brunswick) was designated. Parks Canada provided funding for the development of two river nominations, one river designation and 14 decennial heritage river monitoring reports.

5) National Cost-Sharing Program for Heritage Places

Parks Canada’s National Cost-Sharing Program for Heritage Places (formerly known as the National Historic Sites Cost-Sharing Program) is a contribution program that encourages and supports the protection and presentation of places of national historic significance that are not administered by the federal government. The program supports the Agency’s mandate of protecting and presenting nationally significant examples of Canada’s cultural and natural heritage. In 2012, the program’s terms and conditions, which were initially approved by Treasury Board for a five-year period in 2008, were extended by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada.

During the reporting period, the program received 203 applications. Eighty-one cost-sharing projects were approved for an approximate $6 million commitment. Parks Canada’s investment in these projects has helped conserve national historic sites of every period, size, style and type. As a result of the cost-sharing model, Parks Canada’s contributions have encouraged an additional $14 million in public and private sector investments to support heritage conservation.

This cost-sharing program has been expanded to include all federally recognized heritage places that are neither owned nor administered by the Government of Canada. As of 2016–17, financial assistance is available to heritage lighthouses and heritage railway stations, in addition to national historic sites. The Government of Canada has invested a further $20 million over the next two years to preserve these treasured places while strengthening the tourism sector and supporting the economy.

6) Federal Archaeology

As the Government of Canada’s expert in archaeology, Parks Canada assists other departments in managing archaeological heritage on federal lands and underwater, as set out in the Parks Canada Agency Act and in the Government of Canada’s Archaeological Heritage Policy Framework (1990). Parks Canada provides advice, tools and information to support custodial departments, principally with respect to environmental assessment projects where archaeological resources may be affected. For example, Parks Canada provided advice to Public Services and Procurement Canada related to archaeological resources for projects on Parliament Hill and at the National War Memorial.

7) Federal Heritage Buildings

Parks Canada continues to have a lead role in assisting federal government departments in the protection of heritage buildings, in accordance with the heritage requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on the Management of Real Property. The Agency is responsible for the Federal Heritage Buildings Review Office (FHBRO), which provides heritage advice to departments. The FHBRO manages the heritage evaluation process, including the Federal Heritage Buildings Committee, an interdepartmental and multidisciplinary advisory committee that recommends the designation of federal heritage buildings to the Minister responsible for Parks Canada. The Office reviews proposed interventions to classified federal heritage buildings and is consulted when federal heritage buildings are declared surplus to program requirements and marked for disposal. It maintains a register of designated buildings and develops heritage character statements to assist custodial departments in managing heritage buildings.

In addition to providing FHBRO services to departments, Parks Canada is the largest custodian of federal heritage buildings; it manages 130 classified and 384 recognized federal heritage buildings.

Since 2011, the Minister responsible for Parks Canada has approved nine new designations, joining the more than 1,320Footnote 2 federal heritage buildings across the country. Administered by 23 different departments, these buildings represent some of the most significant places and themes in Canadian history. The Parliament Buildings in Ottawa are an example of one of the 273 classified (highest level) federal heritage buildings, and a rustic warden cabin in Mount Revelstoke National Park is an example of one of the 1,047 recognized (nationally significant, or above-average level) federal heritage buildings.

The FHBRO was able to complete 1,293 evaluation requests received over the last five years, which directly helped guide federal departments in the management of their building inventory.

8) World Heritage Sites

Parks Canada plays the lead role in Canada’s implementation of the World Heritage Convention and acts as the country’s representative internationally. The Agency provides support and guidance to World Heritage Site managers within Canada and to teams working on world heritage nominations. Parks Canada also implements communication plans to inform the Canadian public and interested stakeholders on world heritage issues.

As of March 31, 2016, there were 17 World Heritage Sites in Canada, including the two most recently inscribed sites: Landscape of Grand Pré (2012) and Red Bay Basque Whaling Station (2013). One other site, Mistaken Point was inscribed after the reporting period, during the summer of 2016, bringing the total of World Heritage Sites in Canada to 18. Future nominations will be drawn from Canada’s Tentative List.

Over the past five years, efforts have focused on developing nominations, each of which marks the culmination of years of work by the project team with guidance from Parks Canada. In particular, Parks has been actively supporting a non-profit corporation comprised of First Nations and the provinces of Ontario and Manitoba in preparing the nomination for a site to be recognized equally for its cultural and natural values, Pimachiowin Aki. This site is an exceptional example of the indivisibility of nature and the cultural identity and traditions of Anishinaabe peoples. This nomination has advanced the way in which cultural landscapes are considered within the world heritage community.

The Agency has also laid the groundwork for a number of significant projects, including completion of the second periodic reporting cycle for North America’s World Heritage, in partnership with the U.S. National Park Service. Internationally, Parks Canada has continued to cooperate in the development of world heritage policies for the effective implementation of the World Heritage Convention.

Into the future, Parks Canada plans to move ahead with the update of Canada’s Tentative List for World Heritage Sites. Through this process, Canadians will have the opportunity to suggest additions to Canada’s next set of candidates for World Heritage Sites.

Figure 3: National Historic Sites of Canada Administered by Parks Canada

[text version]

Newfoundland and Labrador

- 1. Ryan Premises

- 2. Hawthorne Cottage

- 3. Cape Spear Lighthouse

- 4. Hopedale Mission

- 5. Castle Hill

- 6. Port au Choix

- 7. Red Bay

- 8. L’Anse aux Meadows

- 9. Signal Hill

- 10. kitjigattalik – Ramah Chert Quarries

Nova Scotia

- 11. Fort Anne

- 12. Alexander Graham Bell

- 13. Bloody Creek

- 14. Grassy Island Fort

- 15. Fort Lawrence

- 16. Grand-Pré

- 17. D’Anville’s Encampment

- 18. Fort McNab

- 19. Georges Island

- 20. Halifax Citadel

- 21. Prince of Wales Tower

- 22. York Redoubt

- 23. Wolfe’s Landing

- 24. Fort Sainte Marie de Grace

- 25. Fortress of Louisbourg

- 26. Melanson Settlement

- 27. Charles Fort

- 28. Port-Royal

- 29. St. Peters

- 30. St. Peters Canal

- 31. Marconi

- 32. Fort Edward

- 33. Canso Islands

- 34. Kejimkujik

- 35. Beaubassin

- 36. Royal Battery

Prince Edward Island

- 37. Ardgowan

- 38. Province House

- 39. Dalvay-by-the-Sea

- 40. Port-la-Joye – Fort Amherst

- 41. L.M. Montgomery’s Cavendish

New Brunswick

- 42. Fort Beauséjour – Fort Cumberland

- 43. La Coupe Dry Dock

- 44. Boishébert

- 45. Fort Gaspareaux

- 46. Carleton Martello Tower

- 47. St. Andrews Blockhouse

- 48. Monument-Lefebvre

- 49. Beaubears Island Shipbuilding

Quebec

- 50. Battle of the Châteauguay

- 51. Carillon Barracks

- 52. Carillon Canal

- 53. Fort Chambly

- 54. Chambly Canal

- 55. Fort Ste. Thérèse

- 56. Louis S. St. Laurent

- 57. Coteau-du-Lac

- 58. Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial

- 59. Fort Lennox

- 60. The Fur Trade at Lachine

- 61. Lachine Canal

- 62. Lévis Forts

- 63. Manoir Papineau

- 64. Louis-Joseph Papineau

- 65. Sir George-Étienne Cartier

- 66. Pointe-au-Père Lighthouse

- 67. Cartier-Brébeuf

- 68. Fortifications of Québec

- 69. Maillou House

- 70. Montmorency Park

- 71. Battle of the Restigouche

- 72. Saint-Ours Canal

- 73. Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue Canal

- 74. Forges du Saint-Maurice

- 75. Sir Wilfrid Laurier

- 76. Fort Témiscamingue

- 77. 57-63 St. Louis Street

- 78. Québec Garrison Club

- 79. Saint-Louis Forts and Châteaux

Ontario

- 80. Fort Malden

- 81. Mnjikaning Fish Weirs

- 82. Inverarden House

- 83. Southwold Earthworks

- 84. Bellevue House

- 85. Fort Henry

- 86. Murney Tower

- 87. Shoal Tower

- 88. Woodside

- 89. Navy Island

- 90. Butler’s Barracks

- 91. Fort George

- 92. Fort Mississauga

- 93. Mississauga Point Lighthouse

- 94. Laurier House

- 95. Peterborough Lift Lock

- 96. Point Clark Lighthouse

- 97. Battle of the Windmill

- 98. Fort Wellington

- 99. Queenston Heights

- 100. Rideau Canal

- 101. Ridgeway Battlefield

- 102. Sault Ste. Marie Canal

- 103. Fort St. Joseph

- 104. Glengarry Cairn

- 105. HMCS Haida

- 106. Trent-Severn Waterway

- 107. Saint-Louis Mission

- 108. Battle Hill

- 109. Battle of Cook’s Mills

- 110. Sir John Johnson House

- 111. Bois Blanc Island Lighthouse and Blockhouse

- 112. Battlefield of Fort George

- 113. Bethune Memorial House

- 114. Kingston Fortifications

- 115. Beausoleil Island

- 116. Carrying Place of the Bay of Quinte

- 117. Merrickville Blockhouse

Manitoba

- 118. Prince of Wales Fort

- 119. Linear Mounds

- 120. Riding Mountain Park East Gate Registration Complex

- 121. Lower Fort Garry

- 122. St. Andrew’s Rectory

- 123. Riel House

- 124. The Forks

- 125. York Factory

- 126. Forts Rouge, Garry and Gibraltar

Saskatchewan

- 127. Motherwell Homestead

- 128. Batoche

- 129. Fort Battleford

- 130. Battle of Tourond’s Coulee/Fish Creek

- 131. Frenchman Butte

- 132. Fort Walsh

- 133. Fort Livingstone

- 134. Fort Pelly

- 135. Fort Espérance

- 136. Cypress Hills Massacre

Alberta

- 137. Banff Park Museum

- 138. Cave and Basin

- 139. Skoki Ski Lodge

- 140. Sulphur Mountain Cosmic Ray Station

- 141. Frog Lake

- 142. Howse Pass

- 143. Athabasca Pass

- 144. Jasper Park Information Centre

- 145. Jasper House

- 146. Bar U Ranch

- 147. Rocky Mountain House

- 148. First Oil Well in Western Canada

- 149. Yellowhead Pass

- 150. Abbot Pass Refuge Cabin

- 151. Maligne Lake Chalet and Guest House

British Columbia

- 152. Nan Sdins

- 153. Chilkoot Trail

- 154. Fort St. James

- 155. Kootenae House

- 156. Gitwangak Battle Hill

- 157. Fort Langley

- 158. Rogers Pass

- 159. Gulf of Georgia Cannery

- 160. Stanley Park

- 161. Fisgard Lighthouse

- 162. Fort Rodd Hill

- 163. Kicking Horse Pass

- 164. Twin Falls Tea House

Yukon Territory

- 165. Dredge No. 4

- 166. Dawson Historical Complex

- 167. S.S. Keno

- 168. S.S. Klondike

- 169. Former Territorial Court House

Northwest Territories

- 170. Saoyú-Ɂehdacho

Nunavut

- 171. Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror

- PreviousWorking Together with Indigenous Peoples

- 5Working Together with Indigenous Peoples

- 6(current) Part A: The State of Parks Canada Natural Heritage Places Establishment, Cultural Heritage Programs and Other Heritage Programs

- 7Part B: The State of Canada’s Natural and Cultural Heritage Places Administered by Parks Canada

- Next

- Date modified :