Finding HMS Erebus

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site

Locating the missing HMS Erebus shipwreck was the very opposite of an overnight success story. Modern technology, traditional Inuit knowledge, and sheer tenacity on the part of the searchers resulted in the stunning find of 2014.

HMS Erebus was found on September 2, 2014. The ship appeared on the sonar screen, plain as day. Parks Canada senior archaeologists Ryan Harris and Jonathan Moore had been staring at this screen—or one like it—for years, looking for any sign of Franklin’s lost ships. Today was the day.

You can’t imagine how incredible it felt when, not even halfway on the screen, the shipwreck emerged perfectly recognizable.

Finding HMS Erebus

Transcript

Parks Canada logo

Title: Finding HMS Erebus

Title: with narration by Marc-André Bernier and Ryan Harris, Parks Canada Underwater Archaeology Team

The video begins with shots of the various research vessels that were involved in the search for HMS Erebus.

Marc-André Bernier: The 2014 search for John Franklin’s ships relied on several research vessels.

The Coast Guard’s icebreaker Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the HMCS Kingston from the Royal Canadian Navy, the Martin Bergmann provided by the Arctic Research Foundation, and the One Ocean Voyager from One Ocean Expeditions.

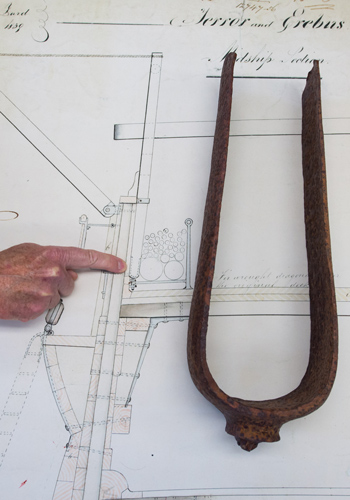

A photograph shows people at an event in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, followed by photographs of a metal artefact from the ship.

Since 2008, the search has drawn from Inuit knowledge, both past and present.

The discovery on an island of a davit fitting from the ship gave a clue as to the location of the wreck.

The underwater archaeology team is seen going about their daily work of searching using side-scan sonar.

The crew is carefully lowering the research vessel Investigator from the well deck of the Coast Guard vessel Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

Ryan Harris: So, each day of the survey, the Parks Canada research vessel Investigator would be carefully lowered from the well deck of the Coast Guard vessel Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

The vessel navigates the water and then we see one of the crew member lowering the side-scan sonar into the water.

From there, we would motor out to conduct a full day of survey with towed side-scan sonar, starting at about 7:00 in the morning and continuing until 8:00 in the evening when we would come back to the ship to refuel and start preparing for the next day.

Various images of Ryan Harris examining the sonar images and from the vessel towing the side-scan sonar.

Marc-André Bernier: So that is how the day goes: we have a sonar image that scrolls along a screen.

In fact, the first images we received in this case showed a complete picture of the wreck. It appeared suddenly.

The wreck sonar image is shown on one of the screens.

There was absolutely no doubt that it was a wreck, and thanks to the measurements that we could take from this image, we knew it was one of the Franklin wrecks.

Ryan Harris and other members of the Underwater Archaeology Team are seen looking at a computer screen on the research vessel Investigator.

Ryan Harris: Well, we’re looking at the first sonar contact that we’ve imaged since starting the survey here in 2008.

We surveyed one line in this new interesting survey area, so this is the second line in this new area, and we had just started southbound on the second line and passed right over top of this wreck structure.

I think we could tell exactly what it was in a few seconds.

It’s definitely a shipwreck and we’ve got to learn a lot more about it.

Jonathan Moore: So that was about what, five, ten minutes ago? Ryan Harris: I would say so.

Jonathan Moore: What was the reaction like? Scientific detachment, or...

Ryan Harris: I would liken it to winning the Stanley Cup.

The Underwater Archaeology Team is seen preparing to launch a remotely operated underwater vehicle.

A few days later, we were able to return once again to the newly discovered site, this time with our remotely operated vehicle, with a high-definition video camera system.

We were able to make a somewhat brief 40-minute dive on the site, where we were able to get the first visuals on the wreck.

Underwater shots of various features of HMS Erebus taken by the remotely operated underwater vehicle.

In that time, we saw a number of features, which clearly reinforced that this was one of Franklin’s ships.

We of course found two cannon off the stern.

Off the port stern quarter of the wreck, we could also see a number of detached deadeyes.

A storm had been blowing for a few days prior to the ROV dive, and that had served to churn up the sea, so it wasn’t very easy to see and so we reluctantly had to recover the vehicle and start planning for a return visit with our diving equipment.

Photos of Prime Minister Steven Harper, Minister of the Environment Leona Aglukkaq and members of the Parks Canada team at the announcement of the find of HMS Erebus.

Marc-André Bernier: Back in Ottawa, the discovery of one of the two ships of the Franklin expedition could finally be announced to Canadians.

The Underwater Archaeology Team is seen preparing to dive on HMS Erebus.

Immediately after this announcement, we returned to the Sir Wilfrid Laurier in order to perform the first dives on the site of the shipwreck.

Time was short. It was really a race against time, but out of a possible five days, we had two where conditions allowed us to dive.

Our goal was to gather as much information as possible to identify the ship, but above all to prepare the next steps.

A diver enters the water, followed by underwater shots of divers exploring HMS Erebus.

Ryan Harris: And certainly it was the most, probably the most remarkable dive I can ever recall in my career.

The wreck site would loom five or six metres overhead, that’s almost two stories tall, standing proud of the sea floor.

And we were struck just by the incredible preservation of the ship’s structures, and the artifacts on site really speaking to the final moments of the ill-fated 1845 Franklin expedition.

Shots of a copper bilge pump.

For example, these beautiful copper bilge pumps on either side of the main mast.

We can actually see examples of these on the ship’s plans.

Shots of two cannon lying amongst broken timbers.

We were struck by the beautiful green colour on the two cannon that are found astern of the vessel.

A diver is seen swimming past a large anchor.

We came across at least six anchors on the site.

Ships destined for polar exploration were outfitted with as many as ten anchors, and it seems that a number of them survive in place.

A diver is seen looking at the sternpost.

We can actually see both an inner sternpost and an outer or end post.

Between the two is where the propeller would have been situated.

Members of the Underwater Archaeology Team onboard the RV Investigator after the dive.

Jonathan Moore: What a dive!

Ryan Harris: That was the best dive of my entire life!

Jonathan Moore: It’s going to take a lot to beat that one.

Ryan Harris: You couldn’t ask for more on this wreck site.

It’s astounding how much is there. Pump heads, the large top of the Massey pump.

Jonathan Moore: Thierry’s going to go bananas with those pumps.

Ryan Harris: And…

Underwater shots of a diver examining the ship's bell.

Jonathan Moore: The ship’s bell.

The bell has a broad arrow on it too.

Underwater shots of divers examining other features of HMS Erebus, followed by shots of the team reviewing a diagram of the ship and of a conservator unwrapping the ship's bell in a laboratory.

Marc-André Bernier: So this is really a magical dive, in which we see not only the ship,

but all the rigging and machinery, making it a truly magical dive

that also gives a glimpse of the incredible opportunities for us to learn about this expedition,

and truly solve the mystery of what happened to the crew of this Franklin vessel that was shipwrecked.

Parks Canada logo.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by Parks Canada, 2015.

Canada wordmark.

Since 2010, Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team (UAT) and their colleagues from various public and private organizations had been “mowing the lawn”—dragging an array of different sensors behind various small vessels in precise, controlled, and plotted lines. The collected data was stored, analyzed, and interpreted in the long months between search seasons. The two search areas are usually only free of ice from late August to early September. In 2014, bad weather in the northern search area meant many of the search ships were concentrated in the southern area.

One of the key breakthroughs in finding HMS Erebus had come only the day before the discovery. And it was made on land, not at sea. On September 1, Government of Nunavut archaeologists had helicoptered to a small island in the southern search area to investigate an Inuit tent ring. On the shore, pilot Andrew Stirling spotted a piece of rusted metal. It looked like the fork of a bicycle, but it turned out to be a davit pintle. This mechanism for raising and lowering small boats exactly matched one on plans of HMS Erebus. The team, including Douglas Stenton, archaeologist and Nunavut’s director of heritage, also found a wooden deck hawse plug (a waterproofing device for a rope-hole). That evening, Stenton transported the finds to the Canada Coast Guard Ship Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the main hub of search activities. On board, the archaeologists examined the artifacts with a growing sense of excitement. The next morning, UAT archaeologist Ryan Harris adjusted his search area based on the new finds. The team continued their lawn-mowing efforts. The wreck was found in minutes.

Once the image appeared on the sonar screen, Parks Canada team members needed to make sure the wreck was of HMS Erebus. They sent down a remotely operated vehicle to collect high-definition video images and compared them to the ship’s plans. But ice was moving in. CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier would soon have to move out. The team had only a few days to dive. The first dive, which Harris described as “the best dive of my life”, verified the wreck was sitting upright on the sea bottom. The largely intact wreck loomed two storeys above the divers’ heads. Among the upper deck boards, divers found bilge pumps and anchors—and, most surprisingly, the ship’s brass bell. A “broad arrow” was clearly visible on the bell’s side. Like the marking on the davit pintle found on shore, the arrow meant the item belonged to the British government.

Documenting an archaeological site is crucial to forming a complete picture. Taking video and photographs, noting structural elements, and plotting finds on a detailed and accurate plan are all part of a thorough archaeological investigation. Moving artifacts alters a site. Knowledge can be lost, so the work is methodical. Every step is recorded. Documenting the site of HMS Erebus was the first job of the UAT. Recovery of some select artifacts would come later. Now that HMS Erebus’s location was known, UAT divers returned in 2015 and in 2016. In the spring of 2015, the team dove under ice, an activity requiring specialized equipment and intense preparation. As part of this joint operation with Royal Canadian Navy divers, the team brought up several artifacts, including a cannon, dining plates, and a medicine bottle.

The 2015 August-September search season started promisingly. “I’ve never seen such a stretch of good weather in the time I’ve been working in this part of the Arctic,” said Gerry Chidley, captain of RV Martin Bergmann. This meant while survey work continued in the northern search area looking for HMS Terror, the underwater archaeologists were able to make dives to HMS Erebus over eleven days, totalling 109 hours underwater. The mission also collected and documented marine biology on and around the wreck. In late August and early September, UAT divers returned to HMS Erebus. More sonar samples were collected around the area. The team used this time to prepare for more in-depth and complex archaeological work planned for 2017. Researchers wanted to document how much the site changed from year to year. Mowing the lawn, year after year

Discovery on land

The best dive of my life

Don’t move anything

Diving under ice

Good weather

2016: a shorter season

Related links

- Date modified :