Finding HMS Terror

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site

Local Inuit information and bad weather combined to make finding HMS Terror in September 2016 an unexpected surprise.

A Two-Pronged Approach

After HMS Erebus was found in 2014, the Underwater Archaeology Team (UAT) had two goals: document Erebus, and find Terror.

Inuit had told of a ship sinking near where HMS Erebus was found. Logic dictated that the other ship might be closer to the site where the crew had abandoned the ships: northern Alexandra Strait. Search efforts in this northern area—dragging sophisticated sonar equipment behind small research vessels and launching autonomous underwater search vehicles—were meticulous, thorough, and tedious. But every hour spent staring at the sonar screen might yield success.

Breakthrough

As it had since 2012, the Arctic Research Foundation’s ship, Martin Bergmann, joined the search. On September 3, 2016, the small vessel was heading from Gjoa Haven to the northern search area when it veered off into Terror Bay, following a remarkable tip.

Sammy Kogvik, a lifelong resident of Gjoa Haven, had only been on the Bergmann for a day. He told a fellow crewmember about seeing a large piece of wood sticking up through the ice in Terror Bay some six years ago while on a hunting trip. This was a personal anecdote by Kogvik but similar accounts of a mysterious ship in Terror Bay had been told by many within Gjoa Haven over the years. Following on Kogvik’s advice, the Bergmann crew decided to drop a sonar scanner and see what they could find.

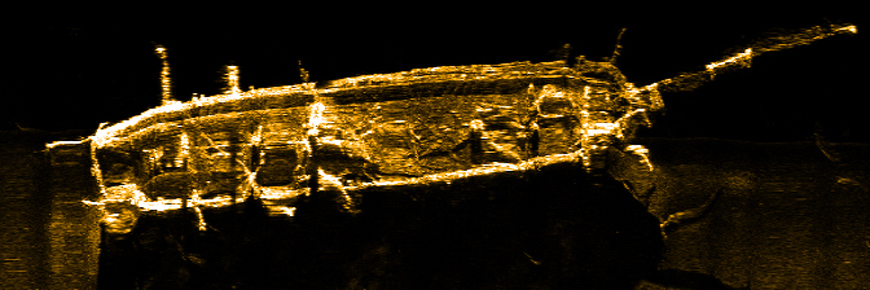

What they found was a three-masted ship upright on the bottom of the bay, almost 100 kilometres from where teammates were surveying the northern search area. Further investigation with a remote controlled vehicle outfitted with a video camera revealed stunning images: intact crew quarters, a mess hall, and a food storage room.

Verifying HMS Terror

The Arctic Research Foundation notified the Canadian government of the find on September 11, 2016. Parks Canada’s UAT, delayed three days by bad weather, sailed to Terror Bay to verify the identity of the wreck.

Three days of diving during difficult conditions turned up numerous clues. Images were checked against copies of 19th century ship drawings. Specific elements such as the double-wheeled helm and iron bow sheathings could only belong to one of Franklin’s ships. On September 18, Parks Canada confirmed the wreck was the missing HMS Terror.

Pristine condition

HMS Terror had come to rest in a sheltered bay. The considerable depth and relatively calm waters have kept it largely intact. Archaeologists noted some hatches and windows were closed—and some window glass was still in place.

“It’s an extremely exciting wreck site to contemplate,” said Ryan Harris, the Parks Canada archaeologist who had been working on the project since 2008. “I think our initial questions relate to why it’s there.”

Collecting images, raising questions

Exploration of HMS Terror continues. During the 2017 Arctic spring, UAT scientists, together with Inuit from the Gjoa Haven Hunters and Trappers Association, set up an ice camp on Terror Bay. The Inuit expertly cut holes in the ice through which the researchers dropped remotely operated vehicles to collect photos and videos. Their observations raise many questions. Although some of the hatches are closed, others are open. It appears a small boat went down with the ship. The ship was not left at anchor. The most tantalizing question of all may be how HMS Terror got there.

Related links

- Date modified :