Underwater archaeology at the Franklin wrecks

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site

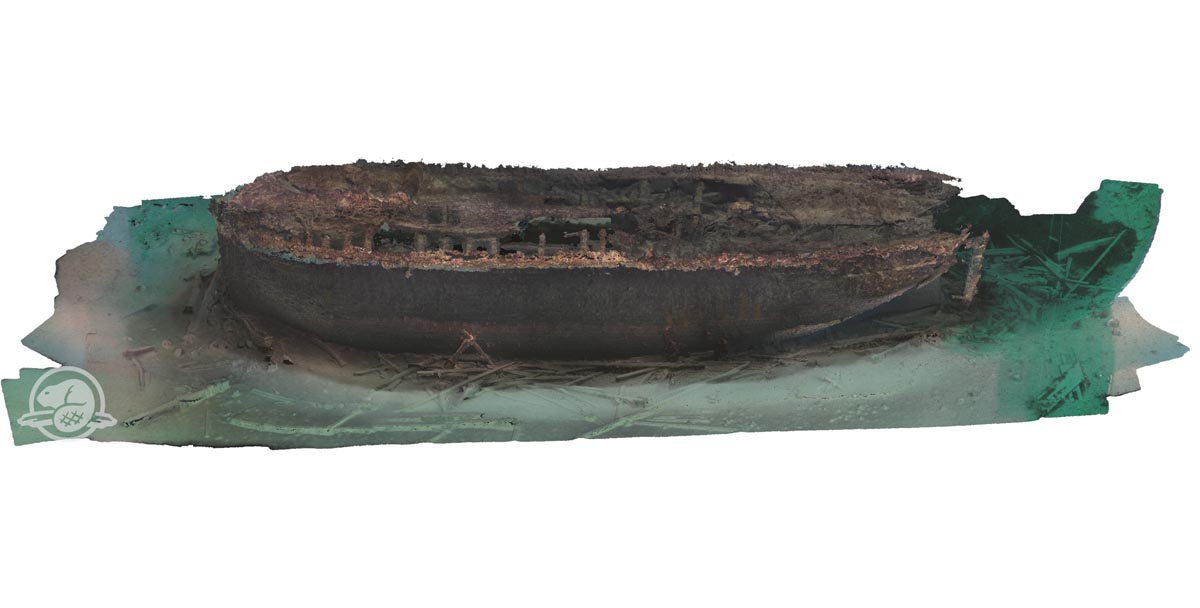

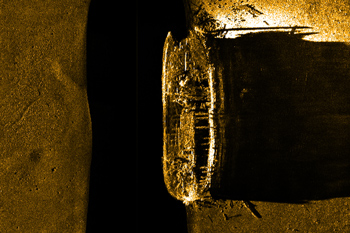

Underwater archaeologists need to consider many challenges when planning their research. Ice and weather conditions in Nunavut only permit a few weeks of diving a year. Individual dives are usually limited to one hour. The wrecks are exposed to currents and extreme ice conditions. Even after 150 years, every second counts. Inuit historian and teacher the late Louie Kamookak described visiting HMS Erebus: “I got to do a traditional blessing with the sand collected from the burial site of our ancestors. This makes them a part of the project, the find, and makes sure the researchers have safe conditions and good weather for their research.” A similar blessing was performed in the waters above HMS Terror in 2018, by Inuit Guardians from Gjoa Haven charged with monitoring the wreck during the open ice season. Managing the logistics of an archaeological investigation is complicated, especially at remote sites. Once a plan for the investigation is in place, the team has to prepare and pack all the equipment. Most of the needed materials and equipment are transported by plane or by ship. Inuk intern Theoran Kopak (steering), Ellen Bertrand of Parks Canada (far right), Jacob Keanik, President of the Board of Directors of the Nattilik Heritage Centre (left) and the late Louie Kamookak, historian and teacher at Gjoa Haven (right) travel to the site of HMS Erebus. Archaeologists use specialized equipment to create an accurate picture of remote underwater sites like Franklin’s shipwrecks. Some of the same equipment used to find the wrecks is also used to explore and document them. Side-scan sonar and multibeam sonar provide images to help the team understand the sites and plan their work. The sonar images also help document the areas around the wrecks. Defining the “debris area” – where parts of the ships have fallen or been scattered – can help archaeologists and historians theorize possible scenarios. Sonar picture of the historic shipwreck as it rests at the bottom of the ocean. Qiniqtiryuaq: A platform for exploration and learning The wrecks’ remote locations make both safe diving and underwater excavation a challenge. In 2017 Parks Canada acquired a barge to serve as an excavation and diving platform at the wreck of Erebus. The barge operates in concert with Parks Canada’s ship RV David Thompson and holds several shipping containers of “sea cans”. The three rugged sea cans house a hyperbaric recompression chamber (to increase diving safety), an archaeological laboratory, and mechanical equipment such as compressors, pumps and generators. A hydraulic crane was be added to its deck in 2018. Nunavummiut suggested names for the new barge in an online contest. The winning name for Parks Canada’s new barge--Qiniqtiryuaq—means “searching for something or person which is (was) lost”.

Members of the Underwater Archaeological Team on the newly named Qiniqtiryuaq in Gjoa Haven. Behind them are the three sea cans that house equipment for the next dive season at the site of Erebus.

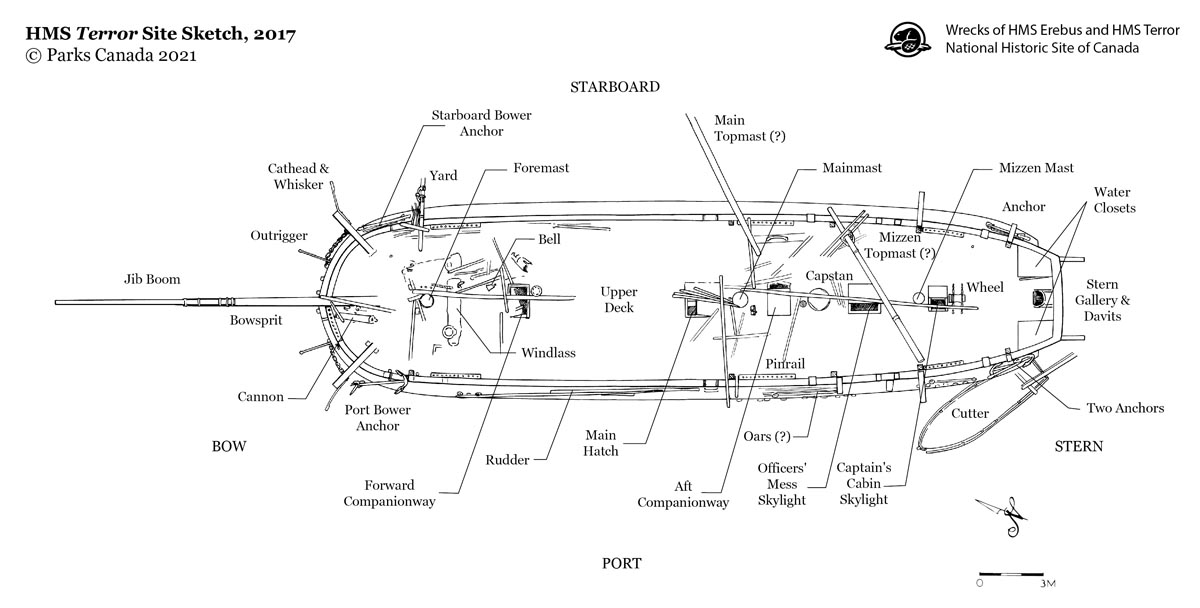

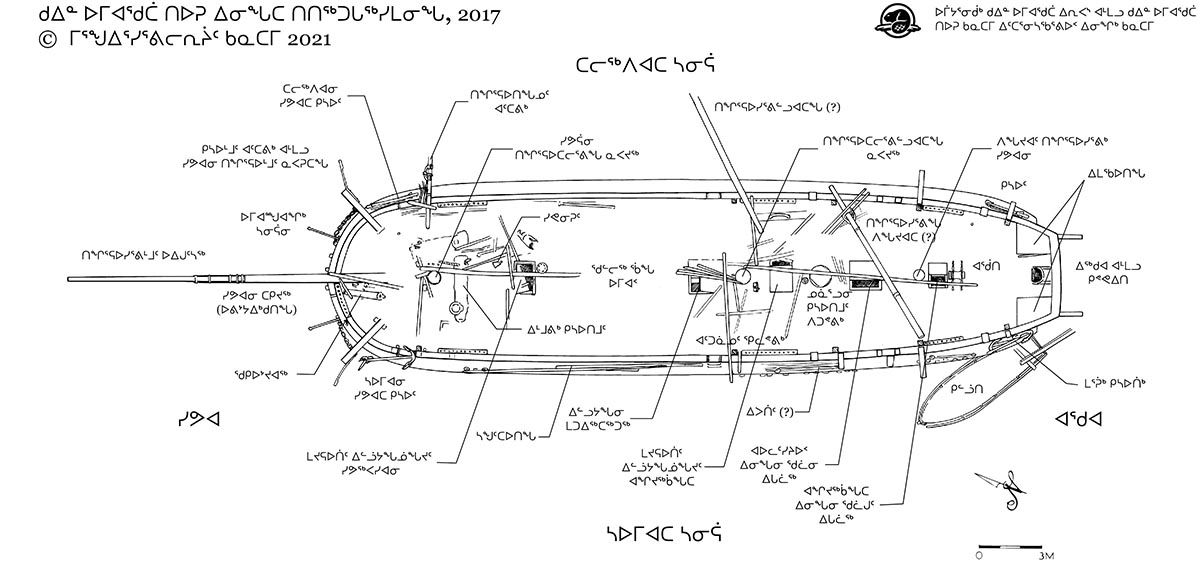

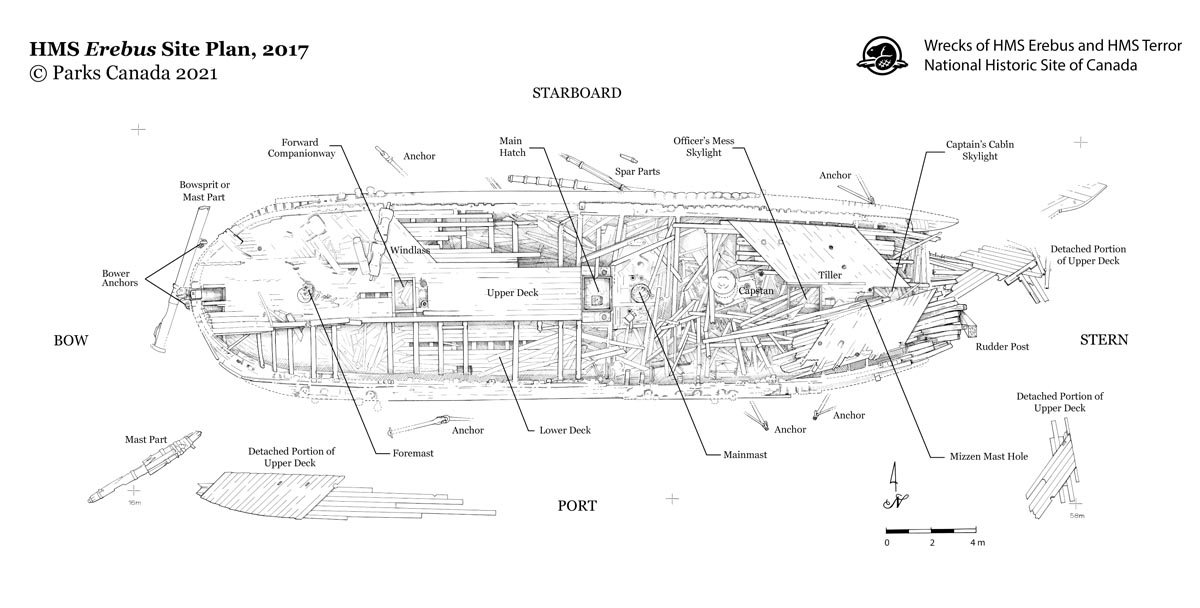

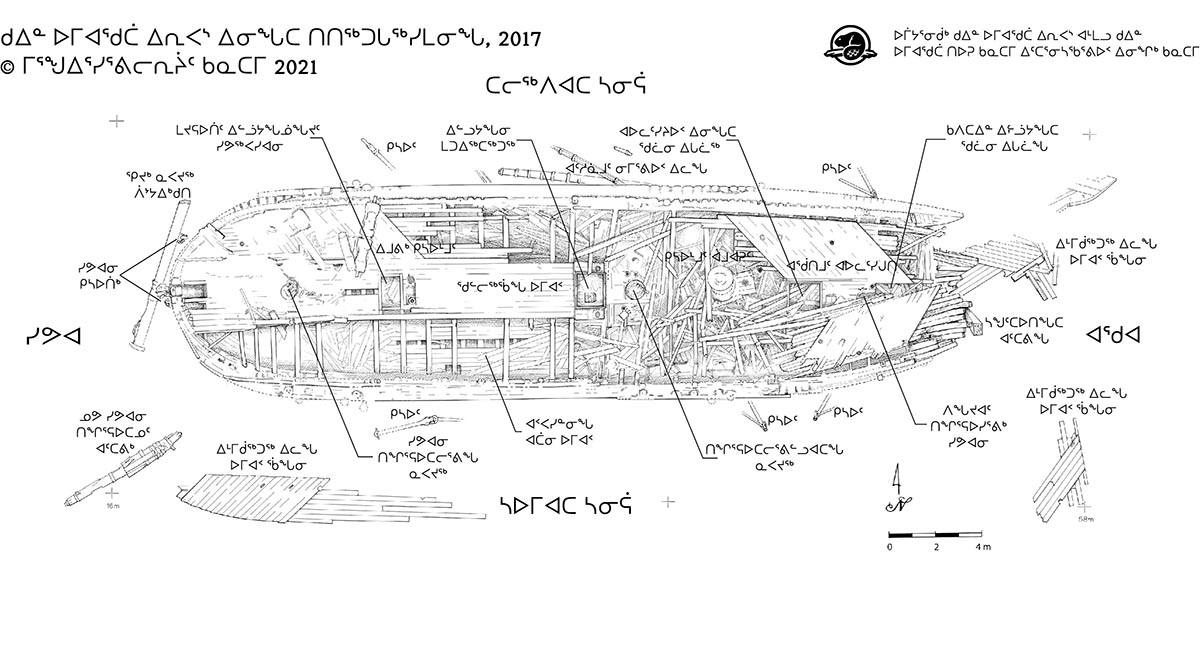

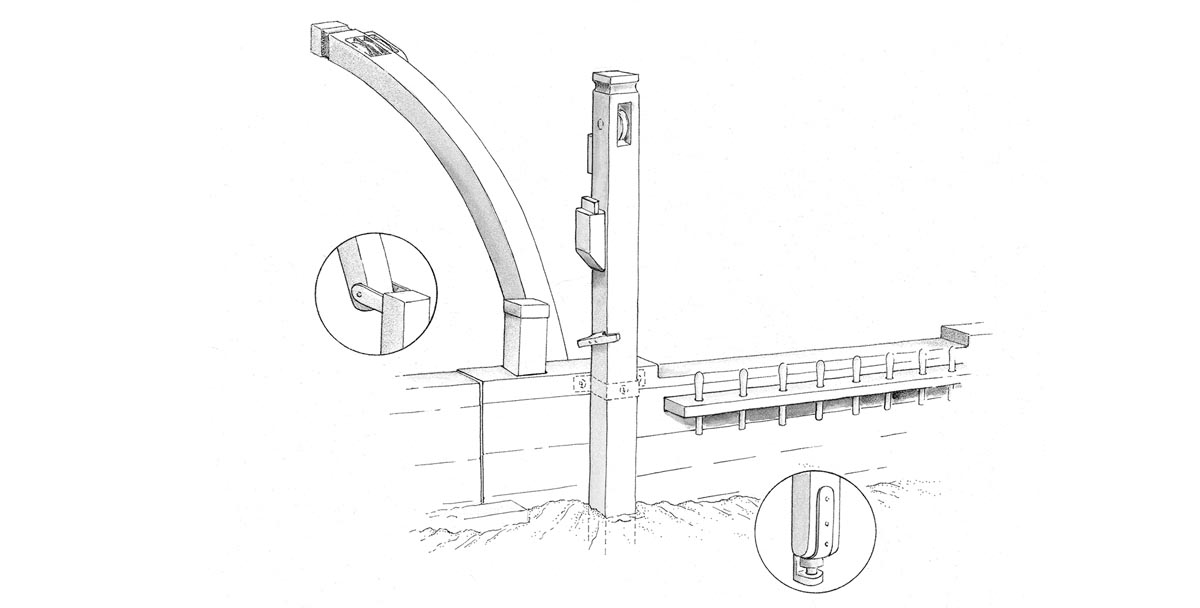

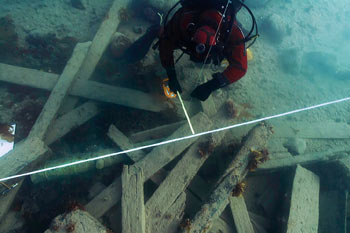

ROVs help explore and document the site with images. The video and still photos ROVs collect can be examined over and over again. Parks Canada staff uses the images to better understand and share information about the shipwrecks. ROVs can also maneuver in tight or potentially dangerous parts of the wreck where a diver can’t go. This little remote controlled submersible robot from the company Deep Trekker went inside the hull of HMS Erebus to take pictures of officer cabins. During August and September, the ocean water in the Arctic hovers a little above 0°C. In conditions like these, a person can freeze to death in minutes. Diving in these conditions is not unusual for Canadian divers. It requires rigorous training and specialized equipment that will hold up to the frigid conditions. Dry suits and masks are designed to cover every single part of a diver’s body and keep them dry. An archaeologist prepares to dive on the HMS Erebus wreck from the Parks Canada research vessel Investigator. Taking notes is difficult to do underwater—large gloves make it hard to press buttons or hold pencils. Notes are necessary to record details and conditions of the site. Special waterproof paper makes the job slightly easier, and can be written on with an ordinary pencil. Above HMS Erebus, a diver takes notes on a clipboard holding waterproof paper. As they do in land-based archaeological digs, archaeologists must set up reference points and often set up a grid to map the site. The grid divides the site into carefully measured units. Archaeologists use this system to map the entire site, describe the contents of each unit and give unique reference numbers to artifacts. Parks Canada archaeologist measuring the position of an artefact using a reference line on the site of HMS Erebus in the “debris field” near the hull of the wreck. A key activity of archaeologists and archaeological illustrators is to create plans that accurately depict sites and their artifacts. Scale site plans and other drawings can be used to understand patterns in artifact finds within a site and they can show how a site changes over time. Illustrations and 3D models can show how shipwrecks and artefacts appear today, as well as how they would have originally looked in the past. Producing archaeological models and illustrations is a painstaking job, using field and laboratory data combined with historical detective work to ensure accuracy. The products presented here build on a variety of sources and are interpreted with the goal to achieve the best historical accuracy while retelling the compelling story of the Franklin Expedition. Franklin’s shipwrecks aren’t the only Parks Canada underwater archaeology sites. For the past 50 years, Parks Canada archaeologists have surveyed underwater sites on all of Canada’s coastlines, in rivers and waterways, and in lakes. Planning the dive

Field work—under pressure, under water

Remotely operated vehicles (ROV) and submersibles

Diving suits

Waterproof paper

Setting a grid

Site plans

Research and reconstructions

Interested in other underwater sites?

- Date modified :