Visitor guide

Fort George National Historic Site

Discovering a National Treasure

Welcome to Fort George, a national treasure that commemorates the War of 1812 - when Canada’s very existence hung in the balance.

At Fort George National Historic Site, we honour the sacrifice of thousands of British forces, Indigenous Allies, and the local Militia, without whom the successful defence of what is now Canada would have been impossible.

This site tells the stories of the historic events that took place, laying the groundwork for over 200 years of peace between Canada and the United States.

It is our goal to provide you with a unique and memorable experience that brings this important part of Canada’s history to life. Thank you for joining us and we hope that you enjoy your visit.

History of the Fort

The British built Fort George between 1796 and 1803 to guard the Niagara River, Navy Hall, and the town (which would eventually become Niagara-on-the-Lake). As Fort George expanded over the years, it shared the role of supply depot with Navy Hall, part of the critical supply route to the upper Great Lakes.

The British military held a strong presence at Fort George in the early 1800s, from the fort’s well-trained and well-organized garrison, to the strategic supply routes and bold leadership under the commander in chief, Major-General Isaac Brock. Yet a much needed allegiance with the First Nations was not assured nor was the loyalty of the many American-born settlers in the area. Tensions were mounting as war loomed over the Niagara Region and Fort George was poised for an invasion.

During the War of 1812, the American campaign in the Niagara region focused on Fort George. In the fall, repeated artillery duels between Fort George and American Fort Niagara damaged defences on both sides of the river. In May 1813, a massive bombardment by American artillery batteries pounded the fort into a smoking ruin leaving the powder magazine as the only building to survive. Two days later, the Americans invaded, forcing the outnumbered British to withdraw. The Americans refortified the site and for the next seven months, Fort George and the town were enemy occupied territory.

In December 1813, the Americans abandoned Fort George and retreated to Fort Niagara across the river. In an act condemned throughout British North America and the United States, they burned the thriving town to the ground, driving inhabitants out into a fierce winter storm. The British then re-occupied the fort, attacked and captured Fort Niagara, and took firm control of the Niagara frontier.

Overall, success in the War of 1812 in the Niagara region was carried out by the British regular forces along side Indigenous warriors and local militia, which included the Coloured Corps - a militia company of Black men. Many sacrificed their lives in the defence of Upper Canada.

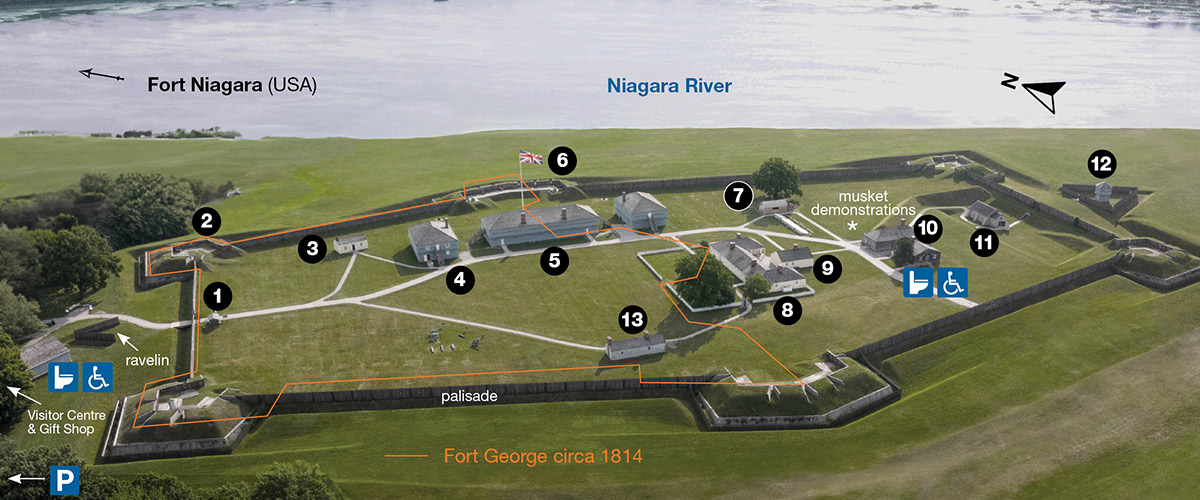

Self-guided tour

For your protection, please do not climb on earthen embankments.

- Front Gates

You will notice that the fort’s main entrance is secured by heavy gates made of massive timbers and reinforced with iron spikes. By day, these gates were open and a sentry was posted to keep careful watch over all who entered. At night, they were closed and locked.

A V-shaped picketing, called a ravelin, in front of the gate served to block the enemy and direct it into the range of the cannon in the raised platforms (bastions) to the left and right. - Brock's Bastion

Brock’s bastion was the fort’s most strategic artillery location. From here, British gunners could aim heavy artillery directly into the heart of the American Fort Niagara and fire on enemy ships attempting to gain access to the Niagara River from Lake Ontario. It is named after Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, who, together with Lieutenant-Colonel John Macdonell, was buried here on October 13, 1812 after the Battle of Queenston Heights. Their bodies were later re-interred in the memorial on Queenston Heights, overlooking the historic battlefield. - The Cottage

This Georgian-style cottage was built sometime after the War of 1812 and represents the type of home an officer or settler might have lived in. In the 1930s, it was moved 90 feet to its current location to allow for the blockhouse one reconstruction. - Blockhouse One

As you enter this building ask yourself this question; Who won the War of 1812? This exhibit explores this question and also looks at the war from the different perspectives of the key players; the British, Americans, First Nations, and the citizens of the Province of Upper Canada. The exhibit makes use of first-hand accounts, historic artwork, and one-of-a-kind artifacts. - Blockhouse Two

For the British Army on the frontier, blockhouses were almost indispensable. These large rectangular buildings served as sturdy barracks and storehouses. A blockhouse was really a fort within a fort and became the last line of defense for the garrison. At Fort George, these buildings served as quarters for soldiers and some of their families, as well as storage. Blockhouse Two could house 200 people with ease if needed. - Flag Bastion

Overlooking the American Fort Niagara and commanding a view across the Niagara River, this bastion is the fort’s largest and was the most heavily armed. The guns from this deck could attack enemy ships, defend Navy Hall, and sweep the grounds from an infantry attack.

Below the bastion stretched the store-houses and wharves of Navy Hall, the local headquarters for Britain’s Great Lakes fleet. This military complex was destroyed by the Americans during the War of 1812. The restored stone building is all that remains of Navy Hall today. - Gun Shed

Artillery was an essential part of just about any type of military operation. Field pieces were smaller and lighter and were designed to be able to move quickly to support infantry in battle. When not in use, these guns were stored in a state of readiness outdoors or in sheds. Early in the war, Fort George had a gun shed on site but its exact location is unknown. - Officers' Quarters

Officers in the British army were educated, cultured, and expected to live like gentlemen, even on the frontier. They attempted to re-create the lifestyle and social standards they were accustomed to in Great Britain and their quarters reflect the background, rank, and interests of the officers stationed to Fort George. - Officers' Kitchen

This building is set up as a full mess kitchen for the officers. It contains typical early 1800s cooking equipment from which an experienced cook could create sophisticated dishes. Army cooks and civilian cooks hired from town were expected to be able to prepare such traditional delicacies as roast beef, fruit tarts, wine sauces, claret jelly, and other favourites. - Artificer's Building

Self-sufficiency was critical in British North America. Thousands of miles of forest, rivers, and ocean separated the colony from Great Britain, the central source of supplies. It was essential that the army employ well-trained and resourceful craftsmen, or artificers.

The carpenter and the blacksmith, the two most important artificers, could repair or manufacture almost any item, from tools for other craftsmen and mess benches for the enlisted men to gun carriages and fort buildings, such as blockhouses. - Powder Magazine

Built in 1796, this powder magazine was the only fort building to survive the War of 1812 which makes it one of, if not the oldest surviving military building in the Province of Ontario. - Octagonal Blockhouse

This small octagonal blockhouse in the centre of the south ravelin (V-shaped picketing) is a replica of the original. Although originally constructed as a defensive position and lookout, it ultimately became an ordnance store-house. - Guardhouse

The guardhouse was the centre of the fort’s daily operations. All visitors – merchants, contractors, suppliers, etc. – were required to report here before proceeding with their business.

For the guards stationed at the sentry posts, the guardhouse was a place to rest between shifts. The shelf bed allowed a few hours of light sleep but soldiers were not permitted to remove their uniforms or equipment while they slept.

Deserters, drunken soldiers, and other unfortunates charged with a crime were confined to small, dark cells. The punishment for most offences was flogging (whipping).

Powder Magazine

During the war, hundreds of barrels of gunpowder were stored within these thick stone walls. Strict precautions in its design along with regulations regarding activities were put in place to prevent an

accidental explosion. An explosion of the magazine would have left much of the fort in ruins and deprived the garrison of ammunition.

On October 13, 1812, a red-hot cannonball penetrated the roof and set fire to the wooden supports. With 800 barrels of gunpowder likely to explode, the garrison deserted the fort in panic. Only a small party of local militiamen and Royal artillerymen remained, led by Captain Vigoreux of the Royal Engineers. They climbed onto the magazine roof, tore off the metal and extinguished the fire before it could ignite the gunpowder. As a result of this near disaster, construction began almost immediately on the earthen berm that protects the building from enemy fire from across the river. It was never hit again.

After the War of 1812

In 1814, looking to replace Fort George, British engineers began the construction of Butler’s Barracks on the plains and Fort Mississauga at the river mouth, employing the Coloured Corps in its construction. Fort George fell into ruin and was abandoned in the late 1820s.

More than a century later, the historic stronghold of Fort George was reconstructed to its pre-1813 appearance and in 1950 it was officially opened to the public. Since 1969, Parks Canada has administered the fort as a national historic site.

Today, we invite you to explore the fort as it appeared before that fateful day in May of 1813; witness the living history demonstrations, chat with our knowledgeable interpretive staff, and experience the feeling of a garrison on the brink of war.

Related links

- Date modified :