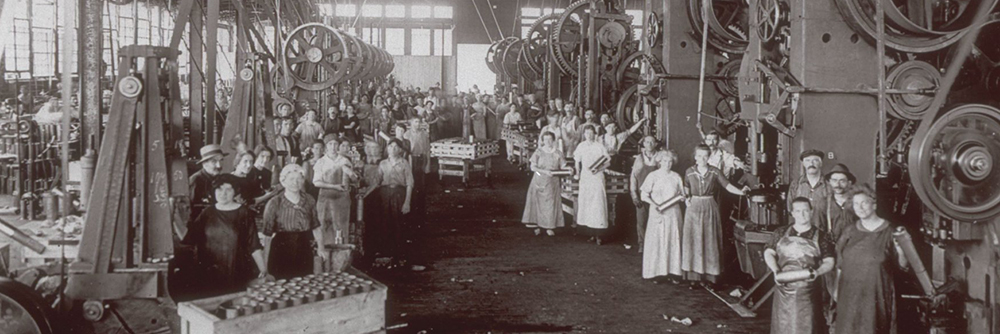

Source: «Women Operating Cartridge Case Presses, Canadian Allis-Chalmers», Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, collection du ministère de la Défense, C 018864, vers 1915

The impact of women on economic development

Lachine Canal National Historic Site

Women have had a major impact on economic and social development in the area surrounding the Lachine Canal. The labour shortage, poverty and the war effort all contributed to women’s entry into the workforce.

Although they were laid off after the war or when the economy began to stagnate, it had become clear that their work was important. Today, let’s pay homage to the efforts of these pioneers, who greatly contributed to the emancipation of 20th-century women.

Women and War Production

At the start of World War I in 1914, Canada not only had to form an army, but also ensure that it was supplied with ammunition, food, clothing and equipment. Because of their size and diversity, the factories along the Lachine Canal soon began to play a key role on the industrial front. In the years following the outbreak of the war, manufacturers along the Canal mobilized all of their resources, increased their production capacity and built new factories. To this end, they recalled the thousands of people they had laid off in summer 1914 and hired thousands of new workers, many of them women.

Women’s entry into traditionally male fields

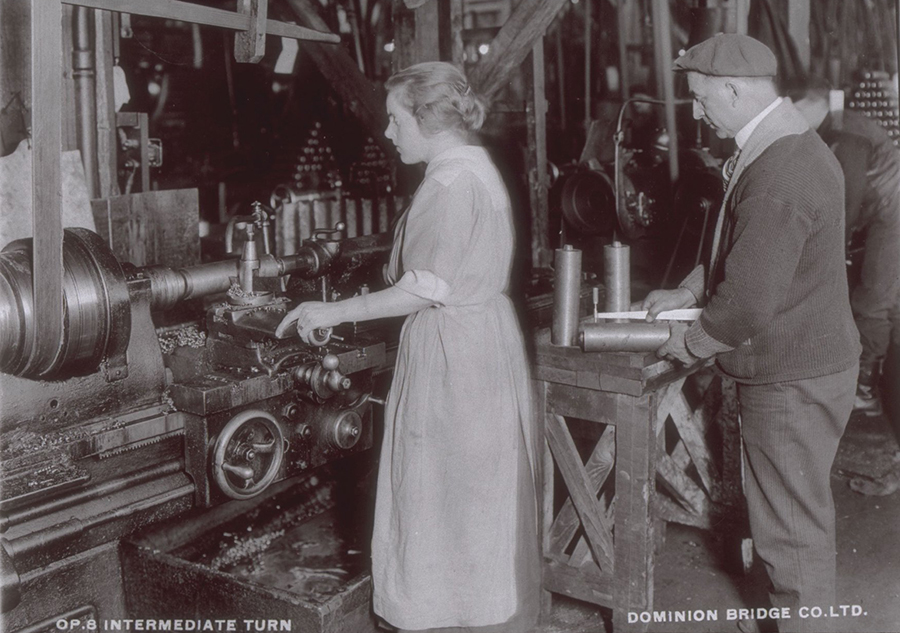

In response to the draft in 1917, ironworks and transportation equipment factories, which had traditionally hired only men, gave women positions that had until then been considered too physically or technically demanding for the fairer sex.Some munitions factories, such as Montreal Ammunition, hired a large number of women. Hundreds of women also landed jobs at Dominion Bridge, Canadian Car and Foundry, and the Grand Trunk Railway Shops.

Dominion Bridge hired women for precision work and even gave them equal pay for equal work. In this, however, the steel bridge constructor stood alone. As a general rule, manufacturers along the Canal paid women less than they paid men. At the end of the war in 1918, most women workers were shown the door.

The Price of Business

Women’s salaries and their participation in the workforce remained dependent on economic conditions. At the beginning of the 20th century, women mostly worked in the garment, textile, leather and tobacco industries, although they also began infiltrating typography, chemicals and electrical appliances.

Unfortunately, the stock market crash of 1929 led to massive layoffs. The women went first, since employers tended to start with employees who did not have a family to support, deeming women’s salaries “extra income.” In addition, some female-dominated industries, such as cotton mills, took advantage of the crash to justify replacing women earning minimum wage with young boys they could pay even less. This technique was used to get around the Minimum Wage Act.

In response, in 1932, the Women’s Minimum Wage Commission asked the Quebec government to intervene. However, the government only formally prohibited the practice in 1934, when the first signs of economic recovery were starting to appear. The Act had many loopholes, but the point is that women’s salaries were dependent on market vagaries. In periods of growth, employers were prepared to pay women a decent salary, but in a crisis, the old habits returned. As proof, in 1934, employers slowly began hiring women again, and women’s basic weekly wages began to rise. In short, the employment situation was improving.

Five years later, in 1939, the country once again found itself at war, and industry needed labour. Montreal women, both single and married, answered the call and, without them, the industrial war would have been lost. At the end of World War II, women were pressured to return to the kitchen, but they had demonstrated their importance.

Portrait of a 20th-Century Working Woman

Between the wars, women workers in Montreal were typically young and single. From Monday to Saturday, they laboured long hours, following the clip of a spinning or sewing machine. Moreover, since they were rarely considered for promotion, their horizons were often limited to the same machine year after year. Most often single, these workers lived with their parents. Whether they earned a salary or were paid by piece work, they brought home little. Often, everything went to feeding the family. If they were to leave home, they would be faced with the monumental problem of finding affordable accommodations. Of course, they could rent a room in a boarding house, but they would have to scrimp on essentials such as food and clothing.

In order to be able to leave home or rise above their situation, many of them chose to marry, since men’s salaries were often twice as high as theirs. Although some married women were forced to work because of poverty or illness, getting married usually meant leaving the workforce.

Strike Actions and Upheavals

It would be incorrect to assume that women were accepting of their situation and did not take action. Between 1919 and 1939, a number of union movements arose in the area. Women were at the heart of almost half of all labour disputes in Montreal.

The most famous movement is without a doubt the dressmakers’ strike of 1937 organized by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. This movement was led by important women militants like Léa Roback and Rose Pesotta. The three-week strike, which lasted from April 15 to May 3, 1937, considerably improved the working conditions of all textile workers.

- Date modified :