© Parks Canada / George Hunter Collection #38-186, 1950

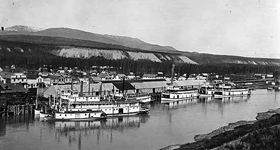

Sternwheelers on the Yukon River

S.S. Klondike National Historic Site

Early days on the lower river

In 1866 the S.S. Wilder, in support of the Russian-American Telegraph initiative, became the first sternwheeler to ascend the Yukon River. Three years later the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC) introduced the regular use of sternwheelers on the lower Yukon River. For the remainder of the 19C the ACC, and later its competitor the North American Trading & Transportation Company, used sternwheelers to supply their trading posts on the Yukon River. Operating from the port of St. Michael, Alaska, near the river's mouth, sternwheelers would carry freight and supplies, as well as fur traders and prospectors, during the short May to September navigation season.

Klondike Gold Rush

When word of the Klondike gold strike reached the outside world in the spring of 1897, it ignited a rush the likes of which has not been seen since. The stampede of people to the Klondike gold fields overwhelmed the few sternwheelers on the river at the time. During the summer of 1897, the boats of 30 new companies appeared to join those already in service. So quickly did word of the wealth of the Klondike affect the outside world that 57 registered steamboats, carrying more than 12,000 tons (10,886 t) of supplies, docked at Dawson City between June and September of 1898. A year later, 60 sternwheelers, 8 tugs and 20 barges were in service on the river.

Sternwheelers on the upper river

While many of these new boats operated on the lower river, from St. Michael, sternwheelers were also introduced on the headwater lakes and the upper river carrying people and supplies that had come over the Chilkoot and White Pass Trails from Dyea and Skagway on the coast of the Alaskan Panhandle.

Sternwheelers operating on the headwater lakes sailed between Bennett, at the northern terminus of the coastal trails, and Canyon City on the upper Yukon River. At Canyon City, a horse drawn tramway, running on wooden rails, was used to carry goods around the treacherous Miles Canyon and White Horse Rapids. From the tiny new settlement of White Horse, located at the base of the rapids, it was a relatively easy 740 kilometre (460 mile) journey by sternwheeler down the upper Yukon River to the booming mining town of Dawson City.

White Pass & Yukon Route

On July 6, 1899, the arduous journey over the coastal passes was eliminated when the narrow-gauge White Pass & Yukon Route (WP&YR) railway was completed between Skagway and Bennett. For a brief time the town of Bennett, at the end of the steel, boomed. A year later the rail line was completed to Whitehorse bypassing Bennett and Canyon City; eliminating two freight transfer points. It was now possible for goods and passengers to be transported from Skagway to Dawson City with only a single transfer point from railway to riverboat in Whitehorse.

British Yukon Navigation Company

The rail line completed, WP&YR moved quickly to extend its dominance in transportation establishing a river division, the British Yukon Navigation Company (BYN). Within a short period of time BYN succeeded in buying out the competition establishing a virtual monopoly on the transportation of goods and people coming into and leaving the Yukon Territory. The dominant pattern of transportation that would serve the Territory for the next fifty years, had been established. Though the boom created by the gold rush was short lived, the development of an efficient transportation system established Dawson City as the supply centre for the upper Yukon River basin.

Commercial mining

While mining continued in the Klondike district, corporate mining interests were acquiring Klondike mining claims and mechanized gold dredges were replacing hand mining operations. Individual hand miners meanwhile fanned out to work other rivers in the upper Yukon basin in search of a new bonanza.

Mayo District silver

Flowing into the Yukon River 112 km upstream of Dawson City, the Stewart River had long been known as the “grubstake river”, where one could reliably make enough to finance further exploration. In 1914 a hard rock silver find on a tributary of the Stewart started a staking rush. In 1918 a second, even richer, ore body was discovered on nearby Keno Hill attracting the attention of corporate mining interests. By 1923 the value of silver coming out of the Mayo District had bypassed the value of gold coming out of the Klondike and would become the backbone of the Yukon economy for the next 50 years. The settlement of Mayo, at the head of navigation on the Stewart River, replaced Dawson City as the supply centre for the new silver mining district.

The silver challenge

For BYN, Mayo District silver was a boon. Unlike placer gold which was melted down into gold bricks for shipment in Dawson City, Mayo District silver was found as a component of galena, a silver-lead mineral, that needed to be shipped out as ore in order to be further processed. Sternwheelers that had previously returned to Whitehorse empty now had a payload – sacks of silver lead ore – for the return trip. From Whitehorse the ore travelled via the WP&YR railroad to Skagway where it was loaded onto ships bound for southern smelters. But the opportunity did not come without challenges.

Transport on the Stewart River

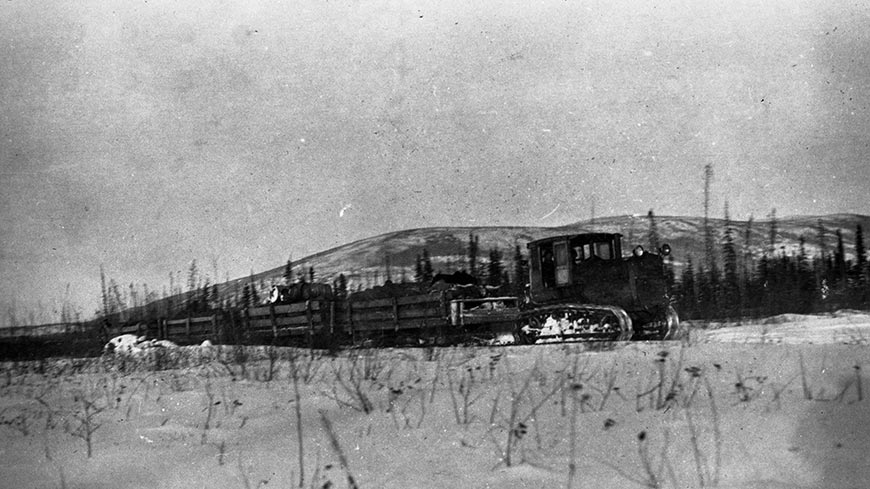

Cat train

The ore from Mayo District mines was transported by “cat train” to Mayo where it would be stockpiled over the winter.

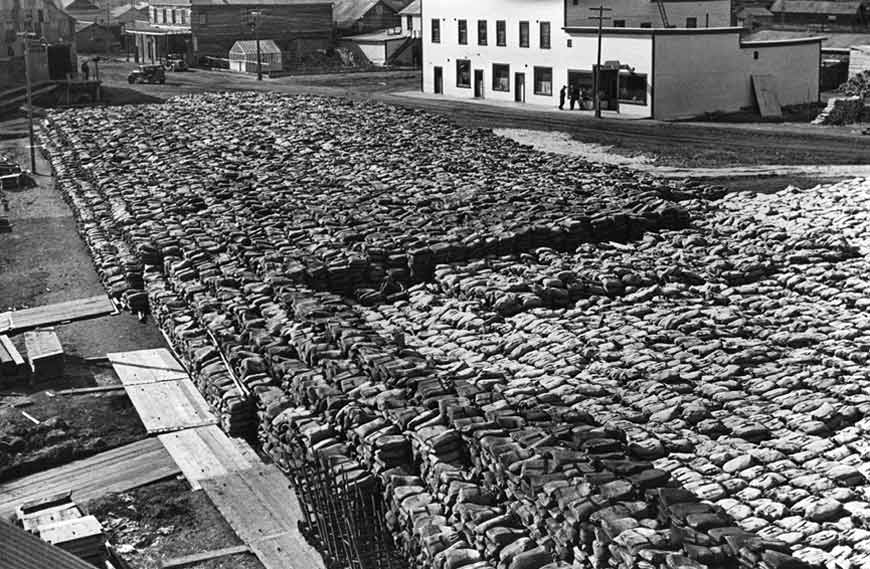

Mayo Landing

Sacks of silver-lead ore stockpiled at the Mayo waterfront on the banks of the Stewart River. “Chateau Mayo” and the General Store are in the background.

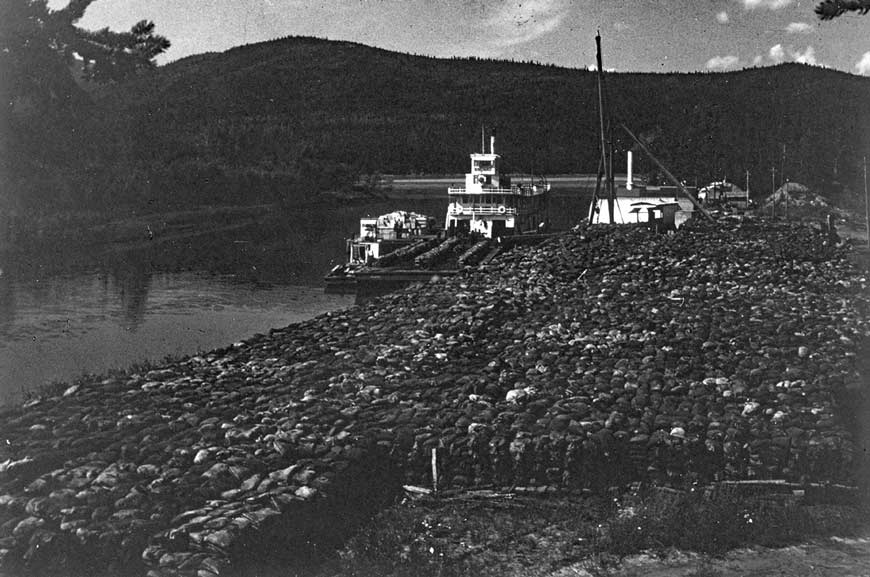

Stewart River

The Aksala moored at Mayo Landing. The Stewart River was shallower than the Yukon, limiting the use of sternwheelers to the brief period of the spring flood.

S.S. Keno

In 1922 BYN built the S.S. Keno for use on the Stewart River. Smaller than the other BYN sternwheelers the Keno could transport supplies to Mayo and carry ore back down to Stewart Landing at the river's mouth for the duration of the navigation season. It usually took 55 hours to come up the Stewart and about 18 hours to go back down.

Stewart Landing

The Nasutlin and a barge moored at Stewart Landing. As the spring freshet subsided and the water level on the Stewart River dropped, the larger boats would load ore at the mouth of the Stewart. They in turn would transport the ore upriver to Whitehorse where it was transshipped via the WP&YR to Skagway.

Ore handling

Each ore sack weighed 125 lbs. At each transshipment point the ore sacks had to be transferred manually using hand trucks. The ore might be handled as many as ten times from mine to smelter.

The larger sternwheelers working the main river at the time did not exceed 51.81 meters (170') in length or 10.66 meters (35') in width. They could carry 180-225 tonnes (198-248 t.) of cargo on a shallow draft of 1.21 meters (four feet). In order to move sufficient quantities of ore they needed to push barges in order to increase their cargo capacity. This meant that the upstream run took half again as much time and fuel.

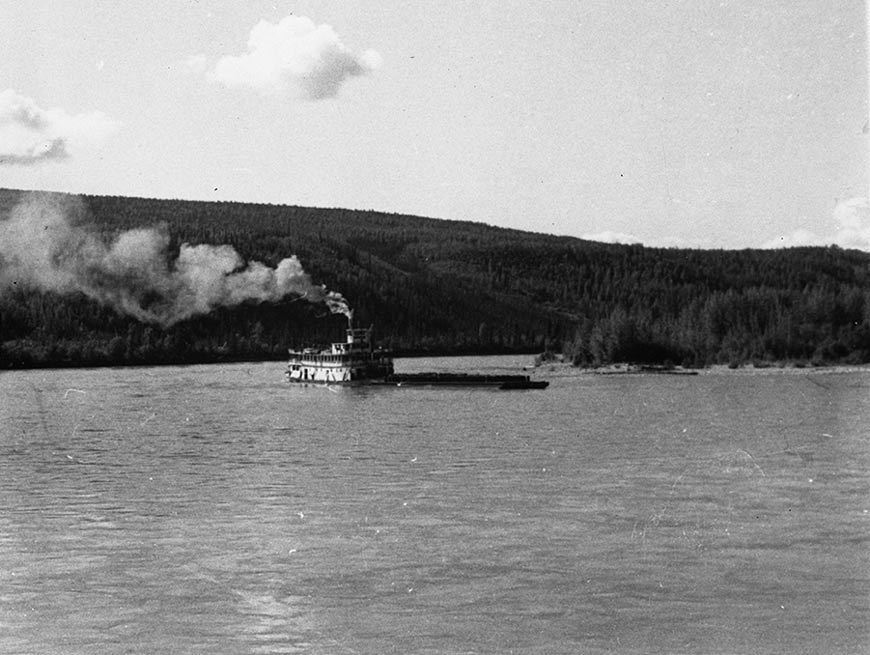

Barging on the Yukon

Bucking the current

Pushing a heavily loaded barge upstream against the current meant that the upstream run took half again as much time and fuel.

Jackknifing

a barge

The Yukon jackknifing a barge. Barges had a recess in their stern into which a punching post attached to the stem of the boat would fit. The post was lubricated with soft soap or grease. The barge was secured to the boat by means of cross lines, and preventer cables allowing it to be jackknifed around a bend.

Cross lines

The movement of the barge was controlled from the foredeck of the vessel pushing it. Cables used to swing the barge ran back from the barge to the winch through snatch blocks on the foredeck.

Retainer cables

Approaching Five Finger Rapids. The degree of swing was limited by retainer cables that ran straight back from the aft corner of the barge to the foredeck of the vessel.

Winch and bell

Deckhands working the winch to steer a barge. The helmsman would direct the deckhands, indicating the manner in which the barge was to be handled by using the jackknife bell.

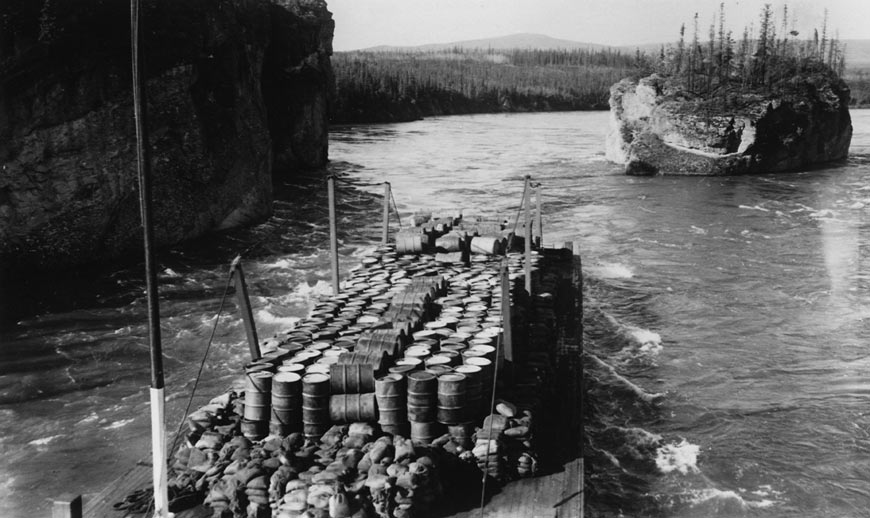

Hazardous goods

Barges were also used to transport hazardous cargo such as barrels of gasoline. When a vessel was pushing a barge with hazardous cargo, passengers were not allowed aboard the vessel.

The solution to moving ore upstream to Whitehorse more efficiently was to build the S.S. Klondike. With a cargo capacity 50 percent greater than other boats on the river, she was large enough to handle a cargo in excess of 272 tonnes (300 tons) without having to push a barge.

Hard times

No sooner had the Klondike been built than the stock market crashed. The impact of the depression on the Mayo silver mining operations was somewhat buffered by increases in efficiency and economies of scale. Despite the depression, the mines kept operating, though at reduced output. The outbreak of the Second World War however soon saw Treadwell Yukon, the main player, shutting down its operations, drastically reducing the volume of ore shipments coming out of the district. The sternwheelers meanwhile were pressed into service in support of the war effort, transporting freight and personel for the building of the ALCAN military road.

Rivers to roads

Mayo District silver mining operations, reorganized under new ownership, resumed in earnest in 1946, giving the BYN sternwheelers a brief reprieve. However the opening of an all weather road between Whitehorse and Mayo in 1950 signalled that the demise of the sternwheeler was near at hand. Ore could now be carried by truck south to Whitehorse on a more or less year round basis overcoming what had always been the Yukon River's chief liability as a transportation route – an open navigation season restricted to only four or five months a year. BYN sternwheelers continued to operate between Whitehorse and Dawson City at reduced capacity until 1952 when the Mayo Road was extended to Dawson City.

- Date modified :