© Parks Canada / G.D. Bissell Collection, #104

Navigation on the upper river

S.S. Klondike National Historic Site

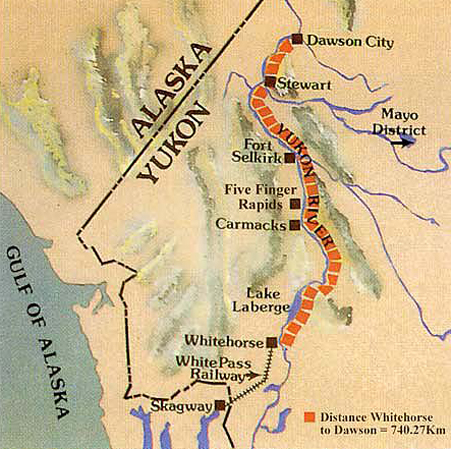

At 3185 km (1979 miles) the Yukon River is the fifth longest in North America. The only serious obstacles to navigation along its entire length were Miles Canyon and the White Horse Rapids, which were bypassed by the White Pass & Yukon Route railway. Whitehorse, located immediately below the White Horse Rapids, was the “end of steel”, transshipment point for freight and base of operations for the British Yukon Navigation Company (BYN) sternwheel fleet.

While not without navigational hazards, the upper Yukon River between Whitehorse and Dawson City was regarded as being relatively straight forward – the sorts of hazards encountered being typical of those found on most rivers on which sternwheelers were employed.

The downstream run

Carrying general merchandise and a few passengers, the S.S. Klondike would make the 740 kilometre (460 mile) downstream run from Whitehorse to Dawson City in approximately 36 hours. This included one or two stops to take on wood.

For the helmsman the downstream run was the most challenging, as the boat, moving with the current, would be travelling more quickly. Pilots had to be skilled at reading the water and handling the boat in order to stay in the main channel of the river. Often the paddlewheel would be reversed to slow the vessel and to help maneuver it.

Drifting a bend

Negotiating a tight bend on the downstream run was particularly difficult. When approaching a sharp bend the paddlewheel would be reversed to slow the boat and position it in the river. Then the paddlewheel would be disengaged, and the force of the current would carry the boat around the bend. Once around the bend the paddlewheel would be engaged full ahead to complete the manoeuvre. This was known as “drifting a bend”.

Shallows and bars

Whenever running a large boat down a shallow river there is a danger of running aground. There were four ways of getting a vessel off of a bar or shallows: washing the sand or gravel away with the action of the paddlewheel, offloading cargo to lighten the draught, running a line to shore and winching off, or sparring. The method selected depended upon the circumstances.

Of the techniques available "sparring" was the most spectacular. The spars were two large timbres equipped with block and tackle. When not in use they were lashed to the forward housing on either side of the main mast. When required they would be lifted from their seats on the foredeck and placed over the side through a chain collar onto the riverbed below. One or both spars might be used and they would be angled depending upon which was the way vessel was to be moved. Using block and tackle connected to the winch, the bow of the vessel could be lifted and the vessel moved, lurching three or four feet at a time. The operation would be repeated until the vessel was free.

Early each season a small work-boat would go down the river to mark the main channel that in sections where it would change each year.

Some pilots maintained detailed charts of the river, which needed to be constantly updated to reflect changing river conditions. Others preferred to rely on memory and their ability to read the river. In either case if there was any uncertainty about the depth of water a man would be positioned on either side of the foredeck (or at the front end of a barge, if a barge was being pushed) to sound the depth using sounding poles, marked with alternating black and white stripes.

"The Flats"

One area where a number of vessels grounded and where special precautions were taken was known as “The Flats”. Located at the head of Lake Labarge where the Yukon River flowed in and deposited large amounts of sediment, the area was shallow with shifting channels. At low water levels the boats would sometimes back over The Flats -- dragging a chain to keep the bow from swing sideways -- the action of the paddle pushing water underneath the hull reduced the amount of water required to get over.

The upriver run

On the return run, the Klondike proceeded first to Stewart Landing 112 kilometres (70 miles) above Dawson City where she loaded sacks of silver-lead ore brought down the Stewart River from the Mayo mining district. Loaded down and fighting the current, the upstream leg of her journey back to Whitehorse could take four or five days with anywhere from five to seven wood-stops.

On the upriver run the speed of the vessel was almost half that of the downstream run allowing the helmsman ample time to pick a channel and set up a manoeuvre. For the fireman in the stokehold the upstream run was a different matter, as the increased power requirements meant that wood had to be fed into the boiler at a rate of more than a cord an hour.

Lining the rapids

At the major rapids – U.S. Bend, Hells Gate, Domville Bar, Rink Rapids and Five Fingers Rapids – steel cables permanently affixed to the shore were used to “line” boats up the rapids using the steam winch mounted on the foredeck. The operation generally would take no more than half an hour but could consume a cord of wood.

At “Five Fingers Rapids” where four massive knuckles of rock split the river into five channels, blasting was also used to make the narrow eastern channel wider and more navigable. Blasting was employed at other locations along the river as well.

Seasonal limits

The greatest limitation to the river transportation system in the Yukon was the shortness of the navigation season. Cold northern winters ensured that the river was icebound for at least seven months of the year.

Spring launch

In the spring, maintenance and repairs were done before the boats were launched for another season. Planks on the hulls may have to be replaced and another coat of paint applied. Just getting a boat off of the cribbing and into the water could take two days or more.

Spring ice on Lake Laberge

In the spring Lake Laberge remained icebound for several week after the river opened. A smaller sternwheeler, such as the S.S. Keno, was often over-wintered in a slough below Lake Labarge that was used to take an early season load of supplies downriver, the supplies having been brought across the lake ice. This vessel would then head up the Stewart River and begin bringing ore, which had been stockpiled at Mayo over the winter, down to Stewart Landing.

Considerable effort was expended in attempts to hasten the break up of Lake Labarge in the spring in order to lengthen the navigation season by a few precious weeks.

A mixutre of lamp black and used crank case oil was often spread along the lake ice to absorb the heat of the sun and promote melting. Its effectiveness was contingent upon a period of sunny weather and could be rendered useless by a late season snowfall. In any event once the ice had disintegrated sufficiently a sternwheeler pushing a steel clad barge would be used to open a channel.

In the 1920s, a dam was built above Whitehorse at the outlet of Marsh Lake. Water impounded the previous summer would be released in the spring raising the water level in Lake Labarge speeding the break up of the ice.

Fall

By mid September, spray from the paddlewheel would start freezing on the rear of the vessels as they made their final runs of the season. By mid October the ice would be forming on Lake Laberge. The sternwheelers were emptied and cleaned. They then had to be hauled out of the water, jacked up and placed on wooden cribbing for the winter.

From rivers to roads

When roads were built in the region in the late 1940s, year round transportation by land became possible, signaling that the end of the sternwheeler was near at hand. When the road to Mayo and Dawson was completed in the 1950s, the fate of the sternwheelers was sealed – roads were to replace the river as the focus of the Yukon's transportation system.

- Date modified :