National priority areas for ecological corridors

On this page

- Ecological connectivity

- National priority areas for ecological corridors

- Map of national priority areas for ecological corridors

- How the map supports connectivity conservation

- Learn more about each national priority area for ecological corridors

- How national priority areas for ecological corridors were identified

Ecological connectivity

Parks Canada works with diverse partners from across North America to maintain and restore the connectivity of habitats. Ecological connectivity is essential to support healthy and resilient ecosystems, including in and around protected areas. Interconnected ecological networks are composed of protected areas and unprotected natural habitats linked by ecological corridors. These networks are key to supporting biodiversity conservation and helping species adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Many protected areas, like national parks, are not connected to other natural habitats. Human activities like urban development, roads, and logging alter the landscape. This impacts how wildlife and even plants move between patches of habitat. Traveling between habitat patches becomes increasingly challenging. Parks Canada’s National Program for Ecological Corridors aims to support connectivity conservation (Guidelines for conserving connectivity through ecological networks and corridors, PDF, 5.5 MB) across Canada. By strengthening ecological networks, we help species move safely between protected areas and other habitats across large landscapes and coastlines.

National priority areas for ecological corridors

Parks Canada has developed a map of national priority areas for ecological corridors (NPAECs) using national-scale data and methods. These priority areas indicate where ecological corridors are most urgently needed in Canada to conserve and/or restore connectivity. Improving or maintaining ecological connectivity in these priority areas will greatly benefit biodiversity conservation and climate change adaptation.

NPAECs identify broad geographic areas in Canada that:

- are critical for terrestrial wildlife movement

- contain high biodiversity values

- are important for species at risk and species of cultural importance

- are experiencing habitat degradation and loss due to development pressure and/or climate change

- contain climate change refugia and/or climate corridors

NPAECs were developed in collaboration with a diverse range of partners, experts, stakeholders and the public. They can be thought of as connectivity conservation ‘hotspots’ and indicate areas where:

- ecological corridors can have the biggest impact towards sustaining biodiversity and ecological functions into the future

- ecological corridor projects can be advanced by local and regional proponents to improve or maintain ecological connectivity

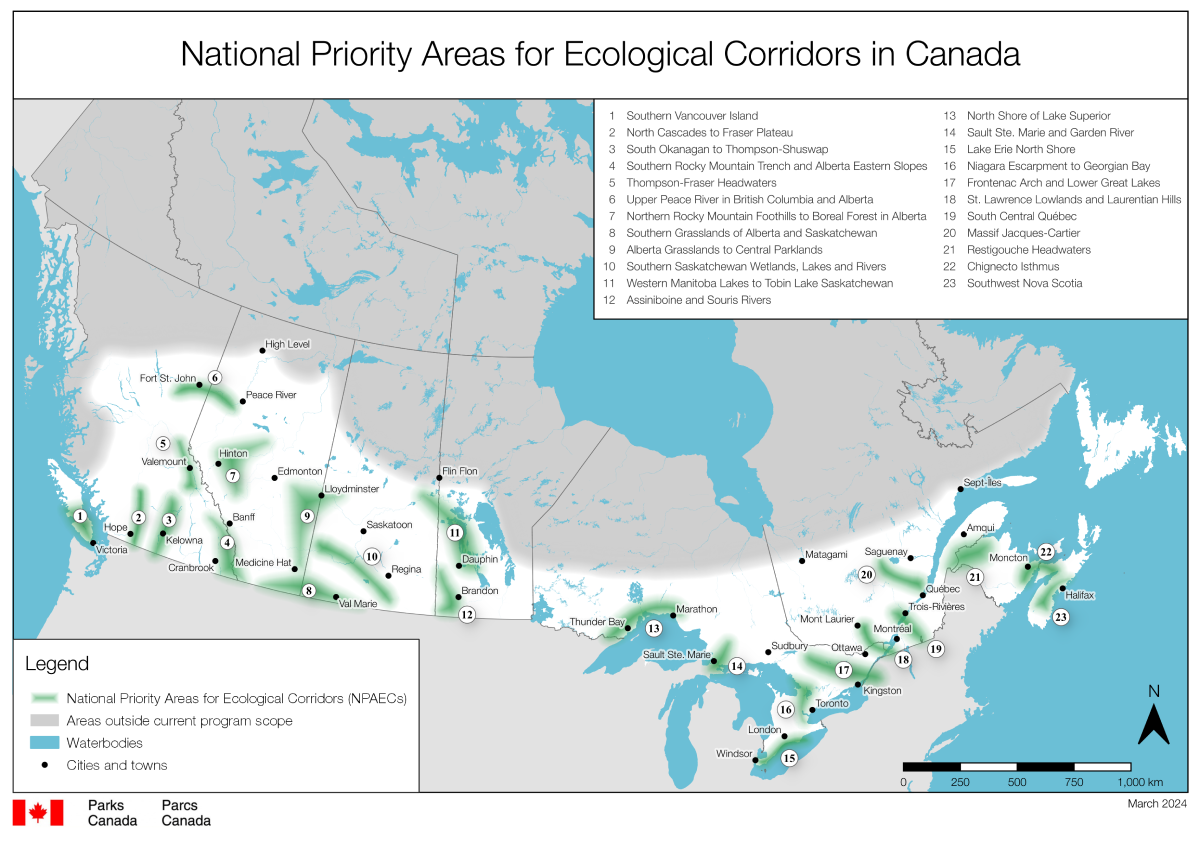

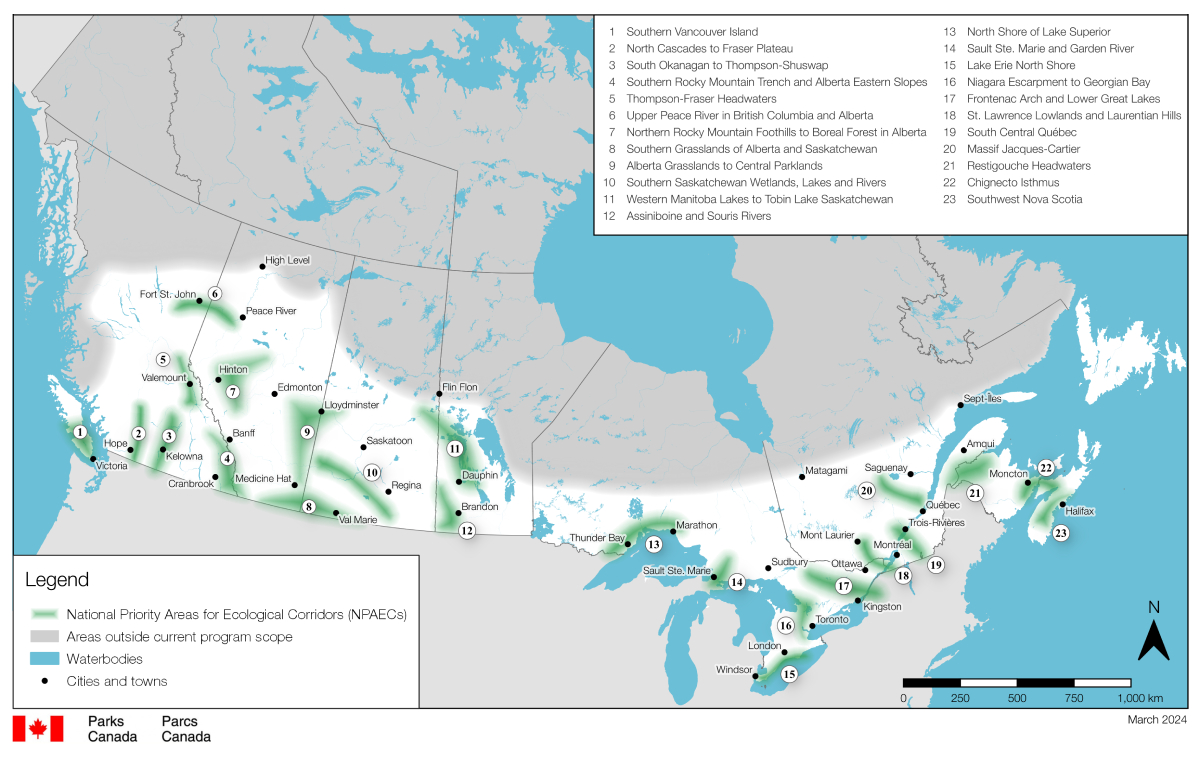

Map of national priority areas for ecological corridors

The map shows 23 priority areas where our analyses indicate that ecological corridors are most needed across the country. Supporting connectivity conservation in these areas will support gains in achieving a well-connected network of protected areas and natural habitats. The map below is interactive. Each of the National Priority Areas for Ecological Corridors can be viewed at different scales, along with associated tools to explore the underlying data.

National priority areas for ecological corridors (NPAECs)

View static map

National priority areas for ecological corridors in Canada — Text version

Interactive map of Canada showing the area of program scope (focused on southern-to-mid-latitudes), the location of each of the 23 National Priority Area for Ecological Corridors and locations of protected and conserved areas in Canada according to the Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database. Major cities in Canada are also displayed for convenience.

- Southern Vancouver Island

- North Cascades to Fraser Plateau

- South Okanagan to Thompson-Shuswap

- Southern Rocky Mountain Trench and Alberta Eastern Slopes

- Thompson-Fraser Headwaters

- Upper Peace River in Alberta and BC

- Northern Rocky Mountain Foothills to Boreal Forest in Alberta

- Southern Grasslands of Alberta and Saskatchewan

- Alberta Grasslands to Central Parklands

- Southern Saskatchewan Wetlands, Lakes and Rivers

- Western Manitoba Lakes to to Tobin Lake Saskatchewan

- Assiniboine and Souris Rivers

- North Shore of Lake Superior

- Sault Ste. Marie and Garden River

- Lake Erie North Shore

- Niagara Escarpment to Georgian Bay

- Frontenac Arch and Lower Great Lakes

- St. Lawrence Lowlands and Laurentian Hills

- South Central Quebec

- Massif Jacques-Cartier

- Restigouche Headwaters

- Chignecto Isthmus

- Southwest Nova Scotia

Each of the priority areas are described in more detail in the section below.

Download map data files

Key context to understand the map

The NPAECs are not ecological corridors. The map shows high priority areas across Canada that were identified as being nationally important for connectivity conservation. They are broad areas where habitat loss and fragmentation have occurred or is imminent, and where the movement of many species across the landscape would be impacted if connectivity was lost. The priority areas can be thought of as national hot spots where ecological corridors are most needed. Supporting connectivity in these areas would have the biggest impact for sustaining biodiversity and ecological functions. Within priority areas, ecological corridors can be advanced to achieve conservation outcomes.

Ecological corridors to be identified and created locally

Identification and creation of ecological corridors is up to local and regional jurisdictions, land managers and stewards, along with experts and knowledge holders. They are best placed to advance ecological corridors based on local knowledge. This includes ecological, cultural, social, political and economic factors. Parks Canada will not identify, create, own or administer ecological corridors. Parks Canada will create tools and resources, like the map, to support and enable corridor initiatives.Focused on southern to mid-latitudes of Canada

Using the right conservation tools in the right places is important. Ecological corridors are most effective in landscapes that are impacted by habitat loss and fragmentation. These are places where connectivity conservation is a priority. In northern Canada, large intact landscapes still exist. Here, the most impactful conservation tools involve establishing large protected areas. However, in the mid to southern latitudes of Canada the landscape is moderately to heavily impacted by human disturbance. This is where our analyses indicate that ecological corridors are most urgently needed to maintain or restore connectivity.Beyond political borders

In order to equally represent the full range of ecosystems and species in the south-mid latitudes of Canada we divided up the country not by province, but by ecozone. Ecozones are large geographic areas with roughly the same land features, climate and organisms throughout them. Using ecozones also highlights areas where trans-border efforts are needed both domestically and internationally.Fuzzy by design

The NPAECs are large, coarsely defined geographic areas that appear fuzzy at their edges. This fuzziness was by design to avoid giving the “illusion of precision” on the boundaries. The fuzziness is a result of the underlying national-scale geographic and ecological data used to create the map. These data are coarse so precise linear delineation of hard edges around the priority areas was not possible, nor appropriate.Terrestrial wildlife movement

The connectivity models used in the analysis are based on predictions of movement for terrestrial species. The models are ‘species agnostic’ meaning they are not based on species-specific data and are not designed to predict movement for a specific species. Movement of some aquatic species and those that use riparian areas are captured in some datasets.A first of its kind map

Parks Canada’s National Program for Ecological Corridors is working to advance connectivity conservation at the national scale. This is the first program of its kind in North America and required novel approaches. The map is based on national-scale data and supplemented by the perspectives of experts and knowledge holders. We anticipate new data and knowledge will become available in the coming years. Therefore, the map may be updated in future years.Connections beyond national parks

Ecological networks for conservation aim to connect natural habitats via ecological corridors. Some natural habitats are protected like in national parks. However, vast areas of natural habitat remain unprotected but are equally important to Canada’s diversity of ecosystems and species. These unprotected habitats also need to be connected. They are represented in our analysis by nationally, and often internationally recognized / designated conservation sites like Biosphere Reserves, Key Biodiversity Areas, and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.How the map supports connectivity conservation

Parks Canada is working to create tools that will assist corridor leaders identify and create ecological corridors, based on science and Indigenous knowledge. Together with the criteria for ecological corridors, the map can support efforts to achieve a well-connected network of protected areas and natural habitats across Canada.

Building these networks requires collaboration among many different individuals and organizations. No one group can tackle the challenge of connectivity conservation alone. The map was developed to be useful to a broad range of audiences including those engaged in land, wildlife, and other natural resource conservation and management.

The map is an evidence-based tool that can be used to:

- inform decisions about where to focus identification and creation of ecological corridors

- guide efforts of local governments, land managers and stewards to restore, enhance, and protect habitats important for connectivity (with other sources of local and regional information)

- address specific conservation challenges, such as resource development, urban growth, and climate change

- support and catalyze on-the-ground projects to enhance and maintain ecological connectivity in priority areas

- foster knowledge co-production, development of tools and partnerships, and allow for the sharing of knowledge and best practices

- promote, inspire, educate and communicate a national vision in support of connectivity conservation

Learn more about each national priority area for ecological corridors

Each of the 23 national priority areas for ecological corridors are described in more detail including:

- brief geographic descriptions

- summary of key factors resulting in the area being identified as an NPAEC

1. Southern Vancouver Island

Geographic description

Covers the entire southern half of Vancouver Island south of Strathcona Park. Includes Vancouver Island only (adjacent small islands excluded).

This priority area connects ecosystems of both land and sea across the southern half of Vancouver Island. This area includes alpine, rainforest, estuaries, rocky coastlines, and Garry Oak meadows. Connectivity mapping shows many options for wildlife movement associated with protected areas. Natural geographic features such as mountains, ocean inlets, and large lakes funnel wildlife into low elevation movement corridors. At the south end of the island, habitat loss and fragmentation restrict wildlife movement dramatically.

Some of the rarest and most endangered habitats in the country occur here. These include old-growth coastal Douglas-fir forests and Garry Oak ecosystems. Southern Vancouver Island is a hotspot for endemic species and species at risk. Over 100 species at risk are associated with Garry Oak ecosystems alone.

This area has experienced habitat loss and fragmentation from forestry operations, recreational and urban development and agricultural practices. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities. Climate connectivity models show that this priority area has high potential to maintain corridors that are climate resilient. These areas connect climate refugia along elevational gradients.

The priority area overlaps with two UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, several Key Biodiversity Areas, and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas. It is in an Environment and Climate Change Canada Place for species at risk.

2. North Cascades to Fraser Plateau

Geographic description

Centered on the Fraser Canyon, extending north from Skagit Valley Provincial Park at the US border to Churn Creek Protected Area. It overlaps with the Stein Valley Nlaka'pamux Heritage Park to the west and Arrowstone Provincial Park to the east.

This priority area connects diverse ecosystems and habitats across a complex landscape. It spans the transition zone between wet coastal forest ecosystems and dry interior grasslands. The priority area overlaps with many protected areas - some of which are well connected (for example, E.C. Manning and Skagit Valley Provincial Parks in British Columbia, North Cascades National Park in Washington).

Connectivity mapping shows numerous options for wildlife movement throughout the priority area. Mountain valleys provide critical connections for wildlife to move between Canada and the United States. Within this priority area, there are many options to connect large protected areas with unprotected natural habitats.

At the north end of the priority area, grasslands thrive in the leeward rain shadow of the Coast Mountains. Grassland ecosystems have high biodiversity and are home to many species at risk. Of note are the unique and fragile bunchgrass ecosystems found in Churn Creek Protected Area that provide habitat for many rare flora and fauna. Further south, the priority area contains critically endangered Grizzly bear populations - the North Cascades and Stein-Nahatlatch population units. Grizzly bears need large tracts of wilderness and access to diverse and seasonal foods like berries, roots and salmon. Here, bears are experiencing habitat fragmentation and population isolation. Protected areas provide important habitat for population recovery. Maintaining and restoring connectivity in this priority area is critical for long term survival of grizzly bears and other wildlife.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats. Habitat loss and fragmentation result from forestry operations, urban development and recreational activities. There are also major transportation routes, particularly highways and railways, that create barriers to wildlife movement. The impacts of these activities act cumulatively. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities and infrastructure. Additionally, this area is under threat from climate change.

3. South Okanagan to Thompson-Shuswap

Geographic description

Centered on the Okanagan Valley, extending from Cathedral Provincial Park at the Canada-United States border north towards Wells Gray Provincial Park. The area extends from the city of Kamloops in the west to Granby Provincial Park in the east.

This priority area includes both the Okanagan Valley and the Okanagan and Shuswap highlands. It contains crucial links through British Columbia’s remaining grasslands, shrub-steppes, and low elevation dry forests that extend north from the United States. The region is known for its many deep, cold, narrow lakes. The priority area is home to more rare, threatened, and endangered species than anywhere else in British Columbia. It is also a significant location for endemic species in Canada.

The landscape in this priority area demonstrates highly restricted wildlife movement due to both natural geographic features and human disturbance. Connectivity mapping indicates few remaining low elevation travel routes for wildlife. This is especially true in the Okanagan valley where the remaining corridors are vulnerable to urban and agricultural development. Some corridors are at risk of being lost entirely for wildlife use. However, this priority area also provides opportunities to maintain and restore landscape-scale connectivity for wildlife. Potential corridors with high probability of wildlife movement exist around the lakes away from urban areas. Maintaining existing connectivity and restoring lost connectivity between natural habitats in this priority area would be highly impactful for wildlife.

This area has experienced habitat loss and fragmentation from agricultural land conversion, urban and recreational development, particularly in the Okanagan Valley, as well as from extractive industries like forestry. The impacts of these activities act cumulatively. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities. The landscape is also a fire prone and fire dependent landscape. Wildfires are becoming increasingly frequent and severe with climate change. The region is also experiencing water scarcity. Climate connectivity models indicate that this area offers climate refugia and climate corridors, both along the valley and at higher elevations.

This priority area is an Environment and Climate Change Canada Priority Place for species at risk and contains Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

4. Southern Rocky Mountain Trench and Alberta Eastern Slopes

Geographic description

Covers the southern Rocky Mountain Trench from the US border to the town of Golden. Bordered by large protected areas in the Rocky Mountains in the east (Banff and Waterton Lakes National Parks) and the Columbia Mountains in the west.

This priority area contains diverse climates and habitats. These include wetlands, grasslands, open forest, closed forest, uplands, alpine, and subalpine ecosystems. The southern part of the priority area extends east to the prairies and foothills of the Waterton Park Front in Alberta and overlaps with the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park World Heritage Site. The priority area includes the headwaters of the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers and the internationally recognized Columbia River Wetlands.

Within this priority area, there are many options to connect large protected areas with unprotected natural habitats. The Rocky Mountain trench is a major natural corridor for north-south wildlife movement in British Columbia. It provides a connection from the United States border in the south to the mountain parks to the north. Throughout the priority area, connectivity mapping shows areas of highly constrained wildlife movement resulting from natural geographic features as well as human disturbance. An example of this is in the Crowsnest Pass, where wildlife movement between valleys is only possible through a narrow pinch point in the mountains.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats including residential and recreational development, forestry operations, oil and gas production and infrastructure, and industrial development. Major transportation routes, particularly highways and railways, create further barriers to wildlife movement. The impacts of these activities act cumulatively. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities and infrastructure. Additionally, this area is under threat from climate change. Climate connectivity models indicate opportunities for climate corridors and climate refugia at higher elevations.

This priority area contains endemic species, RAMSAR wetlands, Key Biodiversity Area, and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas. It overlaps with an Environment and Climate Change Canada Priority Place for species at risk, two Community-Nominated Priority Places for species at risk and with the UNESCO Waterton Biosphere Region.

5. Thompson-Fraser Headwaters

Geographic description

Centered on the northern Rocky Mountain Trench connecting Wells Gray Provincial Park to the west and Jasper National Park to the east. Reaches north to Sugarbowl-Grizzly Den Provincial Park and south to Cummins Lakes Provincial Park.

The core of this priority area is the Robson Valley, along with the northern portion of the Rocky Mountain trench. The Rocky Mountain trench is a major natural corridor for north-south wildlife movement in British Columbia. This priority area provides many options to connect existing protected areas and unprotected natural habitats.

Connectivity mapping in this area shows highly restricted wildlife movement due to the steep mountains on either side of the Rocky Mountain trench, which force wildlife into low elevation corridors. Urban development and transportation infrastructure along the bottoms of these valley corridors further impedes movement of wildlife. Large, protected areas with intact wildlife habitat exist in the eastern, western, and northern regions of the priority area. These areas are important for connectivity and the persistence of many wildlife populations.

This priority area overlaps the watersheds of three major river systems: Fraser, Thompson and Columbia. The Fraser River headwaters are the destination for spawning chinook salmon - the longest spawning run for the species in British Columbia. This priority area also includes ancient stands of western hemlock, western red cedar and Douglas-fir. These old growth forests are essential for southern mountain caribou, a flagship species of this region that persists in small, isolated, and disconnected habitats in this priority area. Maintaining existing connectivity and restoring lost connectivity in this priority area would be highly impactful for wildlife.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by habitat loss and fragmentation resulting from urban and recreational development, forestry and other resource extraction, and agriculture. There are also major transportation routes that create further barriers to wildlife movement in this area. The priority area contains high elevation climate refugia and climate connectivity models indicate high potential for climate-resilient corridors particularly along elevational gradients.

6. Upper Peace River in British Columbia and Alberta

Geographic description

Centered on the Peace River valley from the Williston reservoir in British-Columbia extending east towards the junction with the Smoky River in Alberta. Overlaps with Klinse-Za Provincial Park in the west and arcs east to the town of Peace River.

This priority area extends from the Rocky Mountains in British Columbia eastward to the boreal forest and parklands of Alberta. The Upper Peace Region spans diverse ecosystems. Notably, few protected and conserved areas currently exist in this priority area. In Alberta, protected areas are confined to the Peace River corridor.

Connectivity mapping shows limited wildlife movement potential across this landscape. Movement is restricted to the riparian habitats associated with the Peace River valley. There are few predicted routes for wildlife movement beyond this valley likely due to the extensive human footprint in the region. In British Columbia, the long and narrow Williston reservoir creates a movement barrier that redirects north-south wildlife movement around to the east edge of the reservoir. Protecting remaining opportunities for wildlife movement and restoring lost connectivity in this priority area would be highly impactful for wildlife.

There are unique climatic and ecological conditions in the Peace River area. The Peace River is one of the only watercourses that travels eastward through the Rocky Mountains. It provides a channel for warm Pacific air to flow eastwards, creating a moderated climate. This results in high biodiversity for both forest-dwelling and grassland-associated species. The slopes of the Peace River valley provide important habitat for both prairie and parkland flora and fauna. This includes key year-round riparian habitat and migration corridors for moose, elk and deer. In British Columbia, the priority area overlaps the Klinse-za/Twin Sisters Protected Area and the mountain caribou maternal penning program.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats including agricultural land conversion, urban expansion, forestry and energy development. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities. In the western part of this priority area, there are high elevation climate refugia. Climate connectivity models indicate a high potential for climate-resilient corridors particularly along elevational gradients.

The priority area overlaps with Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

7. Northern Rocky Mountain Foothills to Boreal Forest in Alberta

Geographic description

Triangular area covering the eastern front ranges of the Rocky Mountains, including Jasper National Park. Extends north to the town of Grand Cache and northeast towards Lesser Slave Lake. Reaches south to the North Saskatchewan River.

This priority area encompasses a major ecological transition zone between the Rocky Mountains and boreal forest in Alberta. The landscape varies from sharp mountain ridges to the rolling terrain of the foothills. This area contains many of the headwaters for Alberta’s northern river systems. Due to the diversity of ecosystems, it has a high level of biodiversity.

Connectivity mapping shows a distinctive arch of wildlife movement extending along the front ranges of the northern Rocky Mountains into the foothills and parklands of Alberta. Parts of the landscape show a pattern of highly constrained wildlife movement, such as in the front ranges of the mountains near Jasper National Park. In contrast, other areas like the forested lands in the foothills show numerous options for wildlife to move freely across the landscape. A distinctive pinch point for wildlife movement exists between the east side of Lesser Slave Lake and the developed lands southeast of the Athabasca River.

This area is important for wildlife traveling in and out of the mountains from the central parklands and northern boreal forests of Alberta. The landscape provides habitat for species requiring forest cover to move across the landscape such as elk, grizzly bear, wolf, marten, fisher, lynx, and wolverine. This area is home to several species at risk, including endangered woodland caribou. The entire range of the Little Smoky boreal caribou herd and the winter range of the À La Pêche mountain caribou herd are within this priority area.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats including cumulative impacts from agricultural land conversion, oil and gas production and forestry industries as well as urban and recreational development. This has created a mosaic of fragmented habitats. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities. The priority area contains high elevation climate refugia and climate connectivity models indicate high potential for climate-resilient corridors particularly along elevational gradients.

The priority area overlaps with Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

8. Southern Grasslands of Alberta and Saskatchewan

Geographic description

Runs along the United States border covering most of the Canadian portion of the Milk River basin. Extends from the Twin River natural area in Alberta to Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan. Reaches north to the town of Medicine Hat with the United States border to the south.

This transboundary priority area spans the southern prairies in Alberta and Saskatchewan. The grassland ecosystems within this area have high biodiversity and are home to numerous species at risk and endemic species. Native grassland ecosystems have been largely converted into agricultural lands and are among the most endangered natural habitats in Canada.

Opportunities for animal movement between natural habitats in this landscape are scarce. Connectivity models show narrow isolated channels for wildlife movement along rivers such as the Milk and the Frenchman rivers, as well as near the United States border at the Govenlock and Battle Creek conservation areas. Remnants of natural habitat occur where grazing and agriculture are impractical or where they have been maintained through private land ownership and sustainable ranching practices. Riparian habitats are often the only option for wildlife to move through this landscape. There is an urgent need to work towards a connected network of conservation areas in order to sustain and improve overall habitat connectivity for grassland species.

Grasslands are essential for ensuring the survival of many species at risk including the swift fox, great plains toad, and the greater short-horned lizard. Grasslands also provide important habitat for specialized species that are unique to the grasslands such as pronghorn which is endemic to the prairies of North America. The grasslands of Alberta and Saskatchewan are the only place in Canada where the species occurs. Pronghorn follow the same seasonal migratory routes for many generations. This priority area overlaps with the pronghorn’s core seasonal migration route between summer and winter ranges.

Native communities of plants and animals in the prairies have been impacted by urban expansion, energy development and agricultural land conversion. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation and loss from the continuation and expansion of these activities. This area is also threatened by drought and impacts from climate change.

The priority area overlaps with Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas and spans two Environment and Climate Change Canada Priority Places for species at risk. The priority area also overlaps with the Cypress Hills, an inter-provincial park with unique high elevation ecosystems and an endemism hot spot.

9. Alberta Grasslands to Central Parklands

Geographic description

Triangular area running northwest from the town of Medicine Hat towards Elk Island National Park and stretches to the east past the town of Lloydminster towards Turtle Lake (Saskatchewan) in the north-east.

This priority area covers several natural regions in Alberta and Saskatchewan, including northern fescue, mixed grass grasslands, and central parklands. The ecosystems within this area have high biodiversity and are home to numerous species at risk and endemic species. Human disturbance in this priority area has altered much of the landscape and the native species within it.

Connectivity models indicate narrow channels of north-south wildlife movement in this priority area. These high probability movement areas correspond to remaining natural habitats, often following narrow riparian zones along rivers, lakes, wetlands and streams. Remnants of natural habitat occur where grazing and agriculture are impractical or where they have been maintained through private land ownership and sustainable ranching practices. Riparian habitats are often the only option for wildlife to move through this landscape. There are also very few protected areas in this priority area. The landscape reflects the need to protect remaining opportunities for connectivity between protected areas and remaining natural habitat.

This area provides habitat for numerous rare, sensitive, and at-risk plant and animal species. The fescue grasslands and aspen woodlands of the central parklands provide excellent habitat for moose, deer, snowshoe hare and prairie vole. Pronghorn overwinter in the sagebrush flats along the southern Red Deer River. In the grasslands near Medicine Hat, there are many species at risk such as prairie rattlesnake, plains hog-nosed snake, and Ord’s kangaroo rats. Plant species at risk include small-flowered sand verbena and tiny cryptantha.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by urban development, energy production, and agricultural land conversion. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities. There are also many major transportation routes, particularly highways and railways, that bisect this priority area. This region is experiencing drought and impacts from climate change. Because this priority area contains many opportunities for south-to-north movement it may be important for climate change-related range expansion for many species via maintaining climate corridors.

The priority area overlaps with the Beaver Hills Biosphere Reserve and the Environment and Climate Change Canada Summit to Sage Priority Place for species at risk. It contains a RAMSAR wetland and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

10. Southern Saskatchewan Wetlands, Lakes and Rivers

Geographic description

Centered on Old Wives Lake, Chaplin Lake and Lake Diefenbacher, and extends northeast along the South Saskatchewan River towards the Alberta border and southeast towards McDonald Lake near Estevan.

This priority area is within the prairie ecozone in Saskatchewan and contains a mosaic of grassland communities. The area overlaps with the prairie pothole region, an expansive network of shallow wetlands. These wetlands and grasslands have high biodiversity and provide essential habitat for hundreds of species including species at risk and endemic species. They are also among the most endangered natural habitats in Canada.

Connectivity mapping shows that opportunities for wildlife movement in this priority area are scarce. Movement is restricted to remaining natural habitats in riparian zones along rivers, lakes, wetlands and streams. These small remnants of natural habitat occur where grazing and agriculture are impractical or where they have been maintained through private land ownership and sustainable ranching practices. Riparian habitats are often the only option for wildlife movement through this landscape. Additionally, protected and conserved areas in this region are small and isolated. The landscape in this priority area reflects the need to protect remaining opportunities for connectivity between protected areas and remaining natural habitat.

Grassland habitats in Saskatchewan are essential for ensuring the survival of many species at risk including northern leopard frog and burrowing owl. This area also provides important habitat for specialized species that are unique to the grasslands such as pronghorn. The pronghorn is endemic to the prairies of North America, and the grasslands of Alberta and Saskatchewan are the only place in Canada where the species occurs. Pronghorn follow the same seasonal migratory routes for many generations. This priority area overlaps with the pronghorn’s core seasonal migration route between summer and winter ranges.

The prairies and wetlands in this priority area have largely been converted to agricultural lands resulting in the loss of natural habitats. Habitat in this priority area continues to be at risk from land conversion. This region is also experiencing drought and impacts from climate change.

The priority area overlaps a Key Biodiversity Area and numerous Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

11. Western Manitoba Lakes to Tobin Lake Saskatchewan

Geographic description

Covers most of Lake Winnipegosis's drainage basin. From the north side of Riding Mountain National Park, continuing north past Dauphin Lake and arches northwest into Saskatchewan following the Saskatchewan River towards the north side of Tobin Lake.

The priority area overlaps two ecozones - prairies in the south and boreal plain in the north. It overlaps with the Lake Winnipegosis drainage basin. Lake Winnipegosis is a large body of water that runs from south to north through central Manitoba. Several large, protected areas occur in or near this priority area including Riding Mountain National Park, Duck Mountain Provincial Park and Chitek Lake Anishinaabe Provincial Park.

Connectivity mapping shows many areas with high movement probability, especially associated with the boreal forests in the northern parts of the priority area. Mapping also shows areas of highly constrained wildlife movement resulting from natural geographic features. Multiple thin land bridges between the lakes provide connections for wildlife to move between nearby protected areas and unprotected natural habitats. These land bridges are critical pinch points for wildlife movement. Conserving opportunities for movement at these pinch points is key to maintaining connectivity across this landscape. In the south, agricultural development and transportation networks impede wildlife movement.

The prairie and boreal plain ecozones have high levels of biodiversity. The northern parts of the priority area in Manitoba and Saskatchewan contain habitat for threatened boreal caribou. Boreal caribou, a national priority species at risk, require large intact tracts of intact forest. They undertake seasonal migrations across large home ranges. Because they are sensitive to habitat disturbance, they are a good indicator of the overall health of the boreal forest ecosystems that they inhabit. At the eastern edge of this priority area, Manitoba’s only herd of free ranging wood bison roam around Chitek Lake Provincial Park. Wood bison are also a national priority species at risk and require large areas of intact habitat.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats including cumulative impacts from forestry, agriculture, oil and gas production and mining activities. These impacts have resulted in habitat loss creating a mosaic of fragmented habitats. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities.

This priority area overlaps with several Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas and the Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve.

12. Assiniboine and Souris Rivers

Geographic description

Located in Manitoba, running along the Saskatchewan border and centered around the Assiniboine River. Extends from Riding Mountain National Park south to Turtle Mountain Provincial Park on the United States border and east to Canadian Forces Base Shilo.

This priority area in southwestern Manitoba extends from Turtle Mountain Provincial Park to Riding Mountain National Park. The woodlands, wetlands, and grasslands of this priority area provide varied ecosystems that support high levels of biodiversity. The area also contains some of the last remaining native prairie in Manitoba.

Connectivity mapping shows that opportunities for wildlife movement in this priority area are limited. Movement is restricted to remnants of natural habitats located in riparian zones along rivers, wetlands and streams. This includes the Qu’Appelle, Assiniboine and Souris river valleys. Remnants of natural habitat occur where grazing and agriculture are impractical or where they have been maintained through private land ownership and sustainable ranching practices. Riparian habitats are often the only option for wildlife to move through this landscape. This priority area reflects the need to protect the remaining opportunities for wildlife movement between protected areas and natural habitats.

The native prairie habitats in this priority area are important for many rare and threatened plant species including Prairie Spiderwort, Smooth Goosefoot, and Silky Prairie-Clover. The area is also home to animal species at risk including the Great Plains Toad and the Prairie Skink. The Prairie Skink is Manitoba’s only native lizard and only occurs in Canada in the sandhills west of Brandon. The Canadian population is isolated from other populations in the United States by over 100 km.

Approximately 75% of native prairie in Manitoba has been converted to agricultural cropland and other land uses. Land conversion continues to threaten remaining natural species and natural habitats in this priority area. Roads and highways, including the Trans Canada Highway, bisect this priority area contributing to additional landscape fragmentation. This area is vulnerable to drought and climate change. Climate connectivity models indicate a possible north-south climate corridor is present along the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border, west of Riding Mountain National Park.

This priority area overlaps the Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve, a Key Biodiversity Area, several Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas, and the Environment and Climate Change Canada Southwest Manitoba Priority Place for species at risk.

13. North Shore of Lake Superior

Geographic description

Arcs around the north shore of Lake Superior from the United States border adjacent to Quetico Provincial Park past Nipigon Bay to Pukaskwa National Park in the east and extends inland north to Lake Nipigon.

This priority area contains diverse ecosystems due to its position on the southern edge of the boreal forest and alongside the largest freshwater lake in the world. The landscape is a mosaic of boreal forest with mixedwood species, steep canyons and many lakes. The priority area arcs around much of the northern shoreline of Lake Superior and extends inland to Lake Nipigon. It connects large terrestrial protected areas including Quetico Provincial Park and Pukaskwa National Park. It is contiguous with the Superior National Forest in the United States. It also adjoins Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area.

Connectivity mapping shows this priority area has high potential for wildlife movement in many areas. There are numerous opportunities to connect large protected areas and unprotected natural habitats. Lake Superior itself restricts regional north-south wildlife movements and directs species around to either the west or east sides of the lake. There is also a critical pinch point for wildlife movement between Lake Superior and Lake Nipigon.

This area contains species typical of the boreal forest, as well as several species at risk. Of significance, this area encompasses the most southerly range limit for boreal caribou in Ontario. This species is a national priority species at risk that requires large tracts of intact mature forest with limited human disturbance. The boreal caribou range has already receded northwards due to habitat loss. This trend could be further exacerbated by future changes to habitats resulting from climate change. Other notable species in the region include pockets of white pine, Pitcher’s thistle, sparrow’s-egg lady’s slipper, northern twayblade, and mountain huckleberry found nowhere else in Ontario.

Landscape connectivity in this priority area has been impacted by a diverse range of threats including cumulative impacts from urban and recreational development, forestry, and mining activities. These impacts have resulted in a mosaic of fragmented habitats. Major transportation networks, including railways and the Trans Canada Highway, bisect this area contributing to landscape fragmentation. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation and loss from continued development. Climate connectivity models indicate that wildlife shifting their ranges to find suitable habitats because of climate change may rely on climate corridors in this priority area, particularly around the west side of Lake Superior.

This priority area overlaps with a Key Biodiversity Area.

14. Sault Ste. Marie and Garden River

Geographic description

Comprises the St. Marys River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. Extends from Lake Wenebegon in the north to the United States border in the south. It connects Algoma Headwaters Provincial Park to the west and Mississagi River Provincial Park to the east.

This priority area is centered on the St. Marys River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. It is located in a transition zone between boreal and deciduous forests where the landscape, comprising 2.5 billion year-old Precambrian rock, is dotted with broad shallow lakes and rock-lined channels. It contains stands of old growth white pine and significant wetlands.

The lands around the city of Sault Ste. Marie are essential to landscape connectivity within the Great Lakes Basin. As the key location for wildlife to move in a north-south manner around the east end of Lake Superior or west end of Lake Huron, this priority area acts as a critical pinch point for terrestrial wildlife movement. The city of Sault Ste. Marie itself represents a significant barrier to wildlife movement. Connectivity mapping shows high movement potential away from urban areas in remaining forested habitats. There are many opportunities to conserve regional wildlife movements in this priority area by maintaining connected intact natural habitats.

Forested habitats and wetlands support a diversity of wildlife and rare plants. Large mammals in this area include black bear, wolves, red fox, moose, and white-tailed deer. Wetlands provide important habitat for small mammals such as beavers, muskrat, and mink, and a variety of reptiles and amphibians, including the threatened wood turtle.

Landscape connectivity in this priority area has been impacted by urban development, recreation activities, forestry and energy production. Pollution and river alteration have also contributed to habitat loss along the St. Mary’s River. Railways, roads and highways, including the Trans Canada Highway, bisect this area contributing to landscape fragmentation. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation and loss from continued development. Climate connectivity models indicate this priority area contains a significant, but narrow, north-south climate corridor to facilitate northward range shifts for species.

This priority overlaps with a Key Biodiversity Area and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

15. Lake Erie North Shore

Geographic description

Runs on the north shore of Lake Erie from the city of Windsor (west) to Long Point National Reserve and the Grand River (east). Connects Point Pelee National Park and Rondeau Provincial Park in the south and reaches the city of London in the north.

This priority area along the north shore of Lake Erie in southwestern Ontario overlaps with one of the most fragmented landscapes in the country. The region comprises rich farmland and is densely populated. It is a landscape composed largely of urban areas, extensive transportation networks and agricultural lands. However, many species depend on the remaining natural areas and habitats dispersed across the landscape. Although it only represents 1% of Canada’s landmass, it supports 25% of Canada’s species at risk.

The highly fragmented landscape in this priority area poses numerous challenges for wildlife. Connectivity mapping shows that opportunities for wildlife movement in this area are extremely limited and restricted to remnants of natural habitats. Existing protected areas are small and isolated. Along the shore of Lake Erie there remain some areas with a high probability of wildlife movement, although they are very narrow channels of movement. Maintaining existing connectivity and restoring lost connections between protected areas and natural habitats in this priority area would be highly impactful for wildlife.

This area is an important ecotone as it represents the northern limit of the Carolinian zone which is characterized by deciduous forest and boasts some of the highest biodiversity in Canada. It supports over 500 rare species and many species at risk including the gray ratsnake, common five-lined skink, and Jefferson salamander. Many of these species live in habitats that are not protected.

This priority area covers the most threatened natural region in Ontario. Area of forest cover has declined to 11%, from an 80% historical level. Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats including intense urban, recreational and agricultural development pressures - each resulting in habitat loss and fragmentation. An extensive network of transportation and utility corridors further fragments the landscape. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation and loss from continued development.

This area overlaps with Key Biodiversity Areas and many Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas. It also overlaps with the Environment and Climate Change Canada Long Point Walsingham Forest Priority Place for species at risk.

16. Niagara Escarpment to Georgian Bay

Geographic description

Area centered over Lake Simcoe, from south of the city of Hamilton, extending northwest to Collingwood town, wrapping around Georgian Bay and extending to Parry Sound. The northern edge runs just north of Bigwind Lake and Queen Elizabeth Provincial Parks.

This priority area contains both densely populated urban areas and rural landscapes associated with ‘cottage country’. The habitat along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, north of Waubaushene, is relatively intact, in comparison to the highly fragmented areas south of Georgian Bay. This priority area overlaps with the Niagara Escarpment from the city of Hamilton towards the eastern reaches of Georgian Bay and the west end of the Oak Ridges Moraine. The Niagara Escarpment, a long narrow geological feature, acts as a natural corridor. Its steep slopes and rocky terrain are not suitable for agriculture and development thereby preserving its natural forests.

Connectivity mapping shows that opportunities for wildlife movement in this priority area are limited. Areas with high probability of wildlife movement are localized to the Escarpment itself. Patches of natural habitat are concentrated on the Escarpment and it is one of the few places where wildlife can move in a north-south manner across the fragmented landscape. Existing protected and conserved areas are isolated. In this priority area, conservation actions to maintain existing connectivity and restore lost connectivity between protected areas and natural habitats would be highly beneficial for wildlife.

The wide range of habitats along the Escarpment results in high biodiversity. Common species include black bears and fishers. Several species at risk are present, including snapping turtle, Massasauga rattlesnake, and Jefferson salamander. The forests, lakes, and wetlands along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay provide habitat for the eastern foxsnake, Blanding’s turtle, and northern map turtle.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been subjected to cumulative impacts from intense urban, recreational and agricultural development pressures. The priority area contains many urban centres including Hamilton, Kitchener, Guelph and Barrie, and the west side of Toronto, the most densely populated urban area in Canada. An extensive network of transportation and utility corridors including railways, roads and highways bisect this area contributing to landscape fragmentation. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation and loss from continued development. Climate connectivity models indicate this priority area is a significant climate corridor for wildlife in southern Ontario due to the north-south alignment of the Escarpment. Wildlife shifting their ranges north to find suitable habitats because of climate change may rely on climate corridors in this priority area.

This area overlaps with the Niagara Escarpment Biosphere Reserve and the Georgian Bay Mnidoo Gamii Biosphere Reserve and several Key Biodiversity Areas and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

17. Frontenac Arch and Lower Great Lakes

Geographic description

Spans from east of Lake Nippising eastward through Algonquin Provincial Park just south of the Ottawa River, reaching the St. Lawrence River and the United States border in the Thousand Island area, covering from Kingston to Dupont Provincial Park.

This priority area covers the key transboundary wildlife movement corridor between Algonquin Provincial Park and the Adirondack Mountains in the United States. It contains some of the last remaining large, intact forest and wetland habitats for wildlife movement in the region. The region's complex geology, rugged terrain, and unique climatic conditions result in high biodiversity. In this priority area, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River represent natural barriers for wildlife movement creating an important connectivity pinch point. Wildlife movement is further restricted by the highly developed and urbanized landscape of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Basin.

Connectivity mapping shows this priority area has high potential for wildlife movement on either side of the St. Lawrence River and contains numerous opportunities to connect large protected areas and natural habitats. The Frontenac Arch provides a regionally important forested connection between the Appalachian Mountains and the Algonquin highlands. The islands and islets of the Thousand Islands archipelago act as a land bridge to cross the St. Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes allowing a narrow area of passage through this landscape.

The forests and wetlands of this priority area support high biodiversity and numerous species at risk. Notably there are many reptile and amphibian species such as the eastern ribbonsnake, five-lined skink, gray ratsnake, northern map turtle, and snapping turtle. Mammals with large home ranges such as moose, fisher, black bear, Eastern wolf, and Canada Lynx also use the habitats in this priority area to move across the landscape.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats - each resulting in habitat loss and landscape fragmentation. This area continues to face intense urban and agricultural development pressure along with forestry, expansion of transportation networks and recreational development.

This priority area overlaps with the Frontenac Arch Biosphere Reserve, six Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas, and a Key Biodiversity Area.

18. St. Lawrence Lowlands and Laurentian Hills

Geographic description

Extends northwest from the United States border south of Montreal across the St. Lawrence and Outaouais Rivers. East of Ottawa, it curves north along the Petite Nation River reaching the town of Mont Laurier (west) and Mont Tremblant Québec national park (east).

This priority area connects several ecozones across Ontario and Quebec, - the Boreal Shield Ecozone and the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone. It also covers a transboundary movement corridor between the Laurentian Highlands in Quebec and the Appalachian Highlands to the south in the United States. The St. Lawrence Lowlands are characterized by farmlands, cities, mixedwood forests and wetlands providing habitat for numerous species at risk.

The St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers create natural barriers for north-south animal movement in this priority area. Islands in the rivers act as stepping stones for movement. Connectivity mapping shows that south of the Ottawa River, few remaining patches of intact habitat remain and there is a need to conserve and restore connectivity in this region. The relatively intact ecosystems north of the Ottawa River, present significant opportunities to connect numerous protected areas and natural habitats for wildlife movement.

Diverse habitats in this priority area support high biodiversity and numerous species at risk. The Laurentian Highlands feature lakes and sandy rivers. The Eastern wolf (a rare and genetically distinct relative of the gray wolf), is found in this ecosystem, specifically limited in range to the heterogeneous forest types of central Ontario and southwestern Quebec. The mixedwood forests of the St. Lawrence Lowlands region are home to multiple species at risk, including the snapping turtle and the threatened western chorus frog.

This biodiversity-rich area has been transformed by human development over the past two centuries. Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a range of human activities leading to habitat loss and fragmentation. Agricultural conversion of lands and urban development are ongoing threats along with forestry, expansion of transportation networks and recreational development. Climate connectivity models indicate that the Laurentian Highlands, northeast of Montreal, may become increasingly important as a potential climate corridor as species’ ranges shift northward.

This priority area overlaps with the Environment and Climate Change Canada St. Lawrence Lowlands Priority Place for species at risk, a RAMSAR wetland, and several Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas.

19. South central Québec

Geographic description

Spans from Québec’s Green mountains, north over the St. Lawrence River at Lac St. Pierre, including Bouchard Island (in the west) to the Chêne River (in the east). The area extends north to include La Mauricie National Park and Mastigouche Wildlife Reserve.

This priority area connects several ecozones in Quebec, the Boreal Shield and the Mixedwood Plains. It overlaps with the Green Mountains of southern Québec which extend into the United States. These forested habitats remain largely intact and are important for transboundary wildlife movement. This priority area also includes large tracts of St. Lawrence Lowlands which are characterized by farmlands, cities, mixed woods and wetlands.

The St. Lawrence River creates a natural barrier for north-south animal movement in this priority area. The Islands of Sorel, a small archipelago in Lac St. Pierre provides one of the few possible places in this region where wildlife can cross the river. Connectivity models indicate that this area, along with a narrow stretch of river near Trois-Rivières, are important for wildlife movement. Habitats in the north of the priority area remain relatively intact creating numerous opportunities to connect large protected areas and natural habitats for wildlife movement.

In the southern part of this priority area, the Green Mountains provide habitat for wildlife species with large ranges including black bear and moose. It is also home to species at risk including the wood turtle and the spring salamander. Habitats in and around La Mauricie National Park are a refuge for numerous species at risk including the Eastern wolf, wood turtle, and snapping turtle.

Landscapes in this priority area are fragmented by agriculture, urban and recreational development and forestry. This area continues to face land conversion pressures along with expansion of transportation networks. Climate connectivity models show this area may provide opportunities for north-south climate corridors as species’ ranges shift northward. The area around Lac St. Pierre may become an important climate refugia for many species.

This priority area overlaps with the Lac St. Pierre Biosphere Reserve, a RAMSAR wetland, and an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area. It also overlaps with the Environment and Climate Change Canada St. Lawrence Lowland Priority Place for species at risk, and the Northern Green Mountains Community Nominated Priority Place.

20. Massif Jacques-Cartier

Geographic description

Spans from the St. Lawrence shoreline near l'île d'Orléans northward to the west side of Lac St. Jean. Quebec City is located in the southwest and the area overlaps with Laurentides Wildlife Reserve, reaching south of Réserve faunique Ashuapmushuan.

This priority area extends from the lowlands of the St. Lawrence River northward into the boreal forest. It covers a range of elevations and habitats, from sea level up into the Laurentian Mountains. The forested habitats, wetlands, lakes and river valleys in this priority area are important for wildlife movement. There are many opportunities to connect protected and conserved areas in this region. Connectivity models indicate high movement probability associated with boreal forests in the priority area.

The diverse range of habitats in this priority area results in high biodiversity, including species with large ranges such as moose and black bear. The mountainous area between Québec City and Lac St. Jean provides habitat for one of the last remaining populations of boreal caribou in southern Québec. Boreal caribou, a national priority species at risk, require large tracts of intact old or mature boreal forest. Maintaining and restoring connectivity in this priority area is critical for long term persistence of this species.

Habitats along the St. Lawrence River are fragmented by agriculture, urban development, roads, and railways. North of the lowlands, human pressures in the forested regions include forestry, mining and recreation. This priority area contains high elevation climate refugia and climate connectivity models indicate high potential for climate-resilient corridors, particularly along elevational gradients.

This priority area overlaps the Charlevoix Biosphere Reserve, a RAMSAR wetland, several Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas, an endemism hotspot, and the Environment and Climate Change Canada St. Lawrence Lowlands Priority Place for species at risk.

21. Restigouche headwaters

Geographic description

Covers the border between Quebec and New Brunswick spanning from Chaleur Bay in New Brunswick to the Témiscouata region in Québec. Includes the east branch of the Portage River Protected Area to the southeast and the town of Amqui to the north.

This transboundary priority area spans the borders between Québec, New Brunswick and Maine (USA). It overlaps with the northern Appalachian region, including the Notre Dame Mountains and Chaleur Uplands. Southern parts of the Gaspe peninsula are also included in this priority area. A diverse range of habitats results in high levels of biodiversity in this region. Connectivity mapping shows this priority area has high potential for wildlife movement, particularly between protected areas and natural habitats. The area is important for advancing transboundary connectivity conservation and restoration efforts.

This priority area is in the Northern Appalachian-Acadian ecoregion. The climate and vegetation in this region varies along ecological gradients. Boreal forests occur in the north and deciduous forests in the south; riparian and wetland habitats are dispersed throughout. The priority area has high biodiversity and provides habitat to many species at risk. The region supports mammals including black bear, moose, fisher, marten, and Canada lynx (the latter with significant habitat within the Restigouche watershed). Of note, the headwaters of the Restigouche and St. John Rivers are in the priority area. The Atlantic Maritime woodlands are inhabited by the threatened wood turtle, which requires both forest and freshwater stream habitats.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by urban development, forestry, and mining. A mosaic of fragmented habitats has resulted. Roads and highways, and associated secondary motorized recreation, bisect this area contributing to landscape fragmentation. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation from the continuation and expansion of these activities. This area is also vulnerable to climate change. Climate connectivity models indicate this priority area may provide opportunities for north-south climate corridors as species’ ranges shift northward.

This priority area overlaps an endemism hotspot, Important Bird and Biodiversity Area, and the Environment and Climate Change Canada Wolastoq/ Saint John River Priority Place for species at risk.

22. Chignecto Isthmus

Geographic description

Horseshoe shaped priority area centered on the Chignecto Isthmus. Extends from Cobequid Bay in Nova Scotia and arcs northwest into New Brunswick around the Bay of Fundy coast. The southwest edge overlaps Fundy National Park and extends toward Saint John.

This priority area extends from New Brunswick to Nova Scotia across the Chignecto Isthmus - the land bridge that connects these provinces. This thin strip of land is less than 25 kilometres wide at its narrowest point. It is the only terrestrial route for wildlife to move in and out of Nova Scotia. Connectivity mapping shows this priority area has high potential for wildlife movement. However, wildlife are funneled through the Isthmus, creating a critical pinch point. Maintaining and restoring connectivity in this area is critical for sustaining natural movement of species across this land bridge.

The Acadian forests and wetlands in this priority area have high value for biodiversity. The Chignecto Isthmus is important for wide-ranging mammals such as moose. While there is a stable population of moose in New Brunswick, they are endangered in Nova Scotia. This land bridge provides an opportunity for moose from mainland Canada to migrate to the Nova Scotia peninsula and augment populations.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a range of threats. Natural habitats have been lost and fragmented from activities including agriculture, forestry, urban and recreational land conversion. The Isthmus is a key transportation corridor with a network of roads and railways, including the Trans Canada Highway. This creates additional barriers to animal movement within this critical pinch point. As the only movement corridor for species to move inland, this area will become a crucial climate corridor for potential range expansion for species when responding to a changing climate.

This priority area overlaps the Fundy Biosphere Reserve, multiple Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas, three RAMSAR wetlands, and an endemism hotspot. It also overlaps an Environment and Climate Change Canada Community-Nominated priority place.

23. Southwestern Nova Scotia

Geographic description

Covers all of central Nova Scotia spanning from the Tangier Grand Lake Wilderness Area northeast of Halifax to Kejimkujik National Park and Tidney River Wilderness Area in the south.

This priority area sits in the center of the Nova Scotia peninsula. It connects diverse ecosystems and habitats across a complex landscape. It contains many protected areas. The lands in the central and northern parts of this priority area are densely populated and extensively developed. Connectivity mapping indicates wildlife movement is restricted in many areas throughout the Nova Scotia peninsula and is impacted by the unique geography of the peninsula itself. The exception is at the southern end of the peninsula, where species can move among numerous large protected and conserved areas.

This priority area is a hotspot for biodiversity and species at risk. It contains a wide variety of habitats associated with coastal ecosystems, old growth forests, uplands, lakes, bogs, and wetlands. Notable reptilian species at risk include the wood turtle and the eastern ribbonsnake. The Nova Scotia population of the endangered Blanding’s turtle only occurs in a few locations at the southern end of the peninsula near Kejimkujik National Park.

Landscape connectivity and biodiversity in this priority area have been impacted by a diverse range of threats including cumulative impacts from agriculture, urban and recreational development, roads and highways. The southern part of the priority area faces threats from forestry and resource extraction. Remaining habitats are at risk of further fragmentation and loss from the continuation and expansion of these activities.

This priority area overlaps the Southwest Nova Biosphere Reserve, multiple Key Biodiversity Areas and Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas, and RAMSAR wetlands. It also overlaps the Environment and Climate Change Canada Kespukwitk / Southwest Nova Scotia Priority Place for species at risk.

How the national priority areas for ecological corridors were identified

As a first of its kind program in North America, Parks Canada set out to develop and implement a novel methodology to identify priority areas for ecological corridors at a national scale. The methods are multivariate, data driven, national in scale, and spatially explicit at a coarse resolution.

The methods:

- include both qualitative and quantitative approaches when assessing and validating priority areas

- rely on data and expert advice to identify the priority areas

- build on an existing foundation of connectivity and corridor science

- leverage learnings from around the world

Key methodological steps are summarized below. Spatial data used in the analyses are available on the Open Government Portal.

- Date modified :