.jpg?modified=20230704161524)

Environmental DNA at Parks Canada

All living creatures contain DNA with parts that are unique to their species. These parts are like a genetic fingerprint, they can tell us what species the DNA belongs to. When species shed this DNA from their tissues, hair, and feces into the environment, it’s called “environmental DNA” or eDNA.

By sampling sediment, water, and snow for eDNA, Parks Canada and partners are learning which species are, or have been, present in the environment—even those that are rare or very hard to see. eDNA is one innovative tool Parks Canada is using to inform monitoring programs as we work to protect and restore species and habitats.

Watch how Parks Canada, the Dehcho First Nations, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada are using eDNA research to protect endangered Bull Trout at Nahanni National Park Reserve (Nahʔą Dehé) in the Northwest Territories:

Text transcript

[Morning sun shines through Nahanni National Park Reserve research camp, people discuss plans for the day over a map at camp, a hand releases a bull trout into the water]

[Parks Canada logo]

Parks Canada scientists walk through a river with electrofishing equipment on their backs.

[Title] Field Notes: Searching for Bull Trout - Nahʔą Dehé / Nahanni National Park Reserve

Hello, bonjour, emasi, nakwayaté nahadé, welcome to Nahanni National Park Reserve!

[Aerial shots of rivers and streams throughout Nahanni National Park Reserve]

[Sarah and AJ speak directly into the camera]

My name's Sarah, I'm an ecologist for the park. My name's AJ, I'm a technician working for Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

[Name Tag] Sarah Arnold, Ecologist, Nahanni National Park Reserve

[Name Tag] AJ Chapelsky, Technician, Department of Fisheries & Oceans Canada

So we're out here on the very upper end of Wrigley Creek, looking for Bull Trout.

[Light green map of Nahanni / Nahʔą Dehé appears, identifies three locations: Wrigley Creek, Dahtaehtth’i / Deadmen Valley and Tthenáágó / Nahanni Butte].

[Photo of hands holding a bull trout above a stream.]

Bull Trout are the fish we all care about!

[Illustrated image of bull trout appears in top right corner, labelled Sambaa / Bull trout / Salvelinus confluentus]

A coldwater species that's an important indicator for lots of other fish species in the park. We use them to help us monitor what's going on in the park,

[Hands use a measuring tape to measure a bull trout and then release it back into the stream]

if there's any changes happening to our ecosystems.

[Text] The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and Parks Canada have been working together for over 15 years to study Bull Trout in Nahanni National Park Reserve.

[Text] Bull Trout have very specific habitat requirements and are highly sensitive to habitat changes. Monitoring them can give us early warning about changes to ecosystem health.

[AJ and Sarah speak into the camera while standing in a creek with electrofishing machines strapped to their backs and holding electrofishing nets]

We're using several different methods to catch fish on this project. Electro-fishing is one of them, so I’ve got the magic wand here, and my ghostbusters backpack.

And then I'm going to be following behind AJ, and I'm kind of like the goalie, gotta catch those fish as they come downstream towards me.

[AJ and Sarah stand in a creek using the electrofishing equipment. AJ stands in front of Sarah, while she stands behind him with the net]

[Two other scientists also stand in a creek electrofishing. They give each other a fist bump and then kneel in the creek to retrieve a fish from a net]

[Name Tag] Jessica Olsen, Parks Canada

[Name Tag] Brennan Romaniuk, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

So we've captured our first Bull Trout for the day. Woohoo! We've got a nice-sized one here.

[AJ retrieves a Bull Trout from a blue bag and lays it on a board to measure the fish. He records the results in a small notepad.]

[Text] Tissue samples from Bull Trout are collected and sent across the country to DFO labs.

[AJ writes details of tissue sample onto a small canister that will be sent to the testing lab]

[Text] Trout release!

[Sarah gently releases the trout from the blue bag back into the stream]

The other technique that we're using is something a little bit more recently developed, called environmental DNA, or eDNA. We don't need to see or catch the fish to know

[Sarah speaks into the camera while AJ collects water samples from a stream behind her.

[Other scientists do the same thing, collecting water samples by dipping a small cup attached to a long tube into the moving stream]

that they're there. We can just take a water sample, and then ship them off to the Fisheries and Oceans genetics lab in Winnipeg. Then they process the samples and tell us if there were Bull Trout in this stream or not.

[Text] Electro-fishing gives more detailed information on the fish, but requires time and technical training. eDNA can be sampled by anyone, and allows the team to cover ground more efficiently.

[AJ and Sarah sit in the water while wearing their waders with a mountain view in the background].

One of the best parts of this job is just getting to sit in the pools to cool down on a hot day of sampling.

Absolutely, and I reckon we deserve it. It's been a busy, very full-on week, but it's been a great time.

[Sarah stands near a creek and speaks into the camera while a helicopter lands behind her.]

So it's the end of the day, there's the helicopter coming in to pick us up... another successful day, some more Bull Trout…

[Text] Due to the remoteness of the sample sites, the team makes camp at Deadmen Valley for the duration of the field work.

[Aerial view of helicopter approaching Deadmen Valley campsite. Camera moves toward the Deadmen Valley Warden Cabin]

[Parks Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff relax around camp and prepare food]

[AJ stands next to a river at night and speaks into the camera. He flips the camera around to reveal an orange sunset sky with a backlit mountainscape in the distance.]

One of the things people always ask me about up north is "what's the light like at night?". Well, here we are looking out at the sunset, and it's 12:30 in the morning.

[Sun rises over the river next to camp. Sarah speaks to another team member through a walkie talkie.]

So, it's our last field morning today. Myself and one DFO will be sticking around camp to do some sample processing. Let's go get the day started!

[AJ sits at a table processing samples in clear test tubes with white lids. He’s wearing black gloves.]

[Text] Some eDNA samples are sent for testing at DFO labs in Winnipeg, but some can be tested right here in the field.

[AJ waves Sarah over and she comes to sit next to him at the table to process results.]

Sarah! Come check it out! Our results are in. Check it out...

What am I looking at?

Looks like the reds, our controls, are working. Didn't see much with the greens... nothing in the next three samples. Woo! Bull trout!

Really cool to see that happening in the field while we're sitting in this cabin, you know, not having to wait as long.

[Scenic footage of Nahʔą Dehé / Nahanni National Park Reserve]

[Text] In 2022, the team found Bull Trout in the North and Eastern parts of Wrigley Creek. They’re headed back in 2023 to sample the remaining streams and gather data for a habitat model.

[Text] Parks Canada and DFO work closely with Indigenous partners when planning field studies in Nahʔą Dehé. Methods like eDNA are important tools in making sure that we meet out goal of “yundáa Gogha tu k’ehodí”—waters for life.

[Text] Learn more about how Parks Canada is using eDNA across the country to understand and conserve ecosystems: parks.canada.ca/edna

[Polar Continental Shelf Program logo]

[Fisheries and Oceans Canada logo]

[Parks Canada wordmark]

Jump ahead to learn how Parks Canada and partners are using eDNA to:

- protect endangered species

- catalogue species and measure health

- raise the alarm early on the presence of invasive species

Clues for conservation

Many factors affect the lifetime of DNA in the environment. In general, eDNA can last in the environment for days, weeks, or even years when found in cold conditions. This means it can provide important clues about what species have been present over time. This makes eDNA is an efficient monitoring tool.

eDNA can reduce the need to directly observe species, and can shed light on what species are using, or have used, an environment. It is also less invasive to use eDNA than some traditional monitoring methods. This is an important consideration for sensitive species and environments.

Some species are more rare to see than others. Using eDNA helps us to proactively protect species before recovery is too late.

Important answers to conservation questions

It can take months of fieldwork to monitor ecosystems using traditional methods. Sometimes species are too rare or too small to spot. Scientists can detect eDNA in a fraction of this time. This makes eDNA a valuable complement to traditional biomonitoring methods as we seek answers to important conservation questions.

eDNA may help answer questions about:

- what species have been in an environment

- what habitats they are using and when

- whether an ecosystem is changing

- if restoration efforts are working

Teaming up for success

Like much of what Parks Canada does, working with eDNA requires collaboration with partners, including:

- Indigenous nations and communities

- research labs

- universities

- and others

We incorporate eDNA, and other new techniques, into our conservation toolkit. This helps us better understand how to protect species-at-risk and respond to threats, like invasive species and climate change.

Learn how we are using and testing eDNA as a tool to better protect and conserve ecosystems

-

Protecting endangered species

British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island

Parks Canada and local First Nations are sampling remote rivers in the West Coast Trail unit of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve in British Columbia. They are confirming the presence and absence of important food sources for the Southern Resident Killer Whale, like Chinook and Chum Salmon. Parks Canada is also working with forage fish citizen science groups. They are sampling the sand for eDNA to better understand the distribution of spawning habitat of forage fish that salmon rely on, like the Pacific Sand Lance and Surf Smelt.

This information supports efforts to conserve these important food species and their habitats. This work, in turn, helps protect the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales.

Select images to enlarge

Namekus Lake during the eDNA core sampling Conservation staff in Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan are using eDNA to shed light on a species now gone.

In an interview in the 1990s, Allan Bird, a Chief of Montreal Lake Cree Nation and Senator in Prince Albert Grand Council, shared Traditional Knowledge with staff in the park. Allan was raised in what-are-now park boundaries and was a land user.

The information he shared on place names revealed that Namekus Lake (in Cree ‘namekos’ translates to Lake Trout) once held Lake Trout. He remembered them there before he left to serve in the Korean War, but noticed they were gone from the lake when he returned.

By combining Traditional Knowledge with eDNA and radioisotopic dating techniques, Parks Canada hopes to pinpoint the time that the Lake Trout disappeared.

eDNA allowed us to combine Traditional Knowledge with western science to help tell the story of trout in our park. Traditional Knowledge provided the larger context.

Parks Canada and Queen’s University are studying the presence and absence of the Eastern Musk Turtle at Thousand Islands National Park in Ontario. Ordinarily, conservation staff would canoe, flip lily pads, and swim through wetlands to spot the elusive turtle. With eDNA, staff are able to detect the at-risk turtle in near real-time.

Parks Canada detected the Eastern Musk Turtle using eDNA at Thousand Islands National Park .jpg)

The endangered Eastern Musk Turtle Thousand Islands has a number of species at risk. It’s a challenge to find them and confirm their presence. It’s a great way to find species like turtles, reduce search time, and find new locations by grabbing a sample.

Conservation scientists at Fundy National Park and the University of New Brunswick are exploring the use of eDNA to monitor the endangered Inner Bay of Fundy Atlantic Salmon. Normally it takes months of intense field work to monitor this population. Staff would swim through rivers, use trap nets and electrofishing. Now, an eDNA water sample can determine the presence and absence of Atlantic Salmon.

Researchers are comparing the effectiveness of traditional monitoring efforts against eDNA to determine abundance—with positive results! Conservation scientists are hopeful that eDNA can be used to complement traditional methods. They also hope to scale up this work to monitor the endangered Atlantic Salmon around the whole inner bay.

A University of New Brunswick PhD candidate collects eDNA with Parks Canada to monitor endangered Atlantic Salmon at Fundy National Park

Conservation staff at Prince Edward Island National Park have collaborated with GEN-FISH (a national genomic fish research project) and University of Manitoba. Together, they are developing a method for identifying fish species using eDNA. They are also piloting the use of eDNA to monitor benthic invertebrates as part of the STREAM program.

Conservation staff are now comparing eDNA results against traditional freshwater monitoring methods. They recently discovered a new freshwater mussel in the park. They intend to work with the University of Prince Edward Island to look for this mussel in more locations across the watershed using eDNA.

One of the permanent CABIN sampling sites in Prince Edward Island National Park, where eDNA is being piloted to identify benthic invertebrates

Parks Canada is using eDNA at PEI National Park to monitor the health of freshwater ecosystems -

Cataloging species and measuring health

British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba

Parks Canada, Council of the Haida Nation, Hakai Institute, and McGill University are using eDNA to learn about species in different marine habitats at Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site in Haida Gwaii, British Columbia. They collaborated with many partners on eDNA work, including:

- Council of the Haida Nation

- Hakai Institute

- McGill University

Nearshore and offshore marine habitats have different community structures. Conservation scientists are using eDNA based metabarcoding to identify many of the species that are using eelgrass, kelp, and rocky bottom habitats.

In kelp forests, they found more fish species through eDNA than in one-time visual surveys, although eDNA was less specific than visual surveys for some species. In some cases, the eDNA markers could detect “rockfish” but could not distinguish between species of rockfish.

You can’t replace traditional methods of observation with eDNA because the results need context. We are using eDNA to augment and broaden our sampling, and to sample places we can’t get visually.

This information helps managers and scientists better protect and restore these important marine habitats.

Parks Canada staff and a researcher from Hakai Institute are using eDNA to better understand the community structures of marine habitats. The researcher uses a gloved hand to avoid contaminating the sample with his own DNA.

Parks Canada is inventorying fish species in the Peace-Athabasca Delta in Wood Buffalo National Park. This work was done collaboratively with:

- GEN-FISH

- University of Guelph

- University of Manitoba

- Mikisew Cree First Nation

- Fort Chipewyan Metis Nation

- Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

The Delta is often a challenging place to monitor, requiring nets, electrofishing, and days of time. Now, water samples are being collected to monitor fish populations and changes over time using eDNA.

Conservation staff collected water samples with an Indigenous Community Based Monitoring program and GEN-FISH. Information from eDNA can also be used to show the potential impacts of development projects, like changes in the presence and distribution of species.

Select images to enlarge

Staff at Wapusk National Park in Manitoba are working with GEN-FISH to use eDNA to develop the first full park-wide inventory of fish species. Since only a water sample is needed, using eDNA reduces equipment needs and workload. It is also a non-intrusive way to monitor fish.

Parks Canada and GEN-FISH are using eDNA to create an inventory of fish at Wapusk National Park

-

Raising the alarm early on the presence of invasive species

Mountain national parks, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec

Watch how staff at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba are using eDNA results to help manage the invasive Zebra Mussel

Text transcript

[Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba]

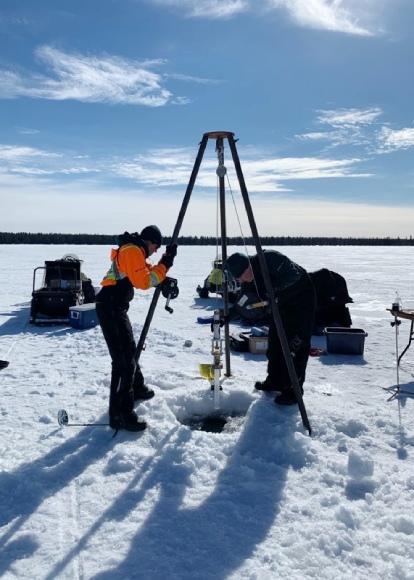

Over the winter of 2022/23 Parks Canada staff learned about the presence of Zebra Mussel eDNA in Clear Lake.

While no Zebra Mussels have been found, staff have increased monitoring and sampling of lake water.

Park staff have been working with members of the Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation.

This is what that work has looked like...

Arrive bright and early!

Time to get packed up.

Gear has been specially cleaned.

Partners from Keeseekoowenin Objibway First Nation are supporting the work.

Shelters are used to keep equipment from freezing up.

Drilling the hole to collect the samples.

Equipment must be kept very clean.

Reviewing today's sites.

A Kemmerer is used to collect water samples.

A weight is used to close the sampler.

Samples are collected in sterile bags and transported to the lab.

An ultra-clean lab space has been set up.

Pumps are set up to filter the samples.

DNA in the water is collected on filters.

The filtering process.

A used filter (left) compared to a new filter (right).

Filters are preserved for different kinds of tests.

A lab in Winnipeg tests filters for Zebra Mussel DNA.

When one site is complete, on to the next!

So far no other evidence of Zebra Mussels has been detected.

Parks Canada staff will continue to work hard to prevent Zebra Mussels--or any other invasive species--from becoming established in...

Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba.

Parks Canada

Canada

Many Parks Canada sites are investigating the use of eDNA as an early detection tool for invasive species. Conservation staff at Lake Louise, Yoho and Kootenay national parks are using eDNA to look for the presence of the parasite that causes whirling disease in certain fish.

This parasite has not yet been detected in the Pacific drainage basins of Canada, home to Trout, Charr, Salmon, and Whitefish. Using eDNA, staff may be able to better limit the introduction and spread of invasive species through early detection and intervention.

Parks Canada is using eDNA alongside sentinel fish cages to monitor for the presence of Whirling Disease in the mountain national parks

Members of the Ontario Water Soldier Working Group are using eDNA in Trent-Severn Waterway National Historic Site to track and prevent the spread of Water Soldier. This invasive aquatic plant has sharp, serrated edges and overtakes native plants. Researchers have detected Water Soldier at varying strengths depending on the location using eDNA.

This tool is helping to manage the aquatic invasion. eDNA helps researchers identify areas to find and remove newly-established Water Soldier plants. This work is helping to inform control and eradication efforts to remove this destructive species from the waterway.

The invasive Water Soldier

The invasive aquatic plant can clog up the lock system in canals Parks Canada is taking a similar approach at Chambly Canal National Historic Site in Quebec. Resource management staff are using eDNA to detect the Round Goby. This invasive fish can eat thousands of native fish eggs in minutes. It has not yet been detected in the Chambly Canal.

Parks Canada is using eDNA to test for the invasive Round Goby fish at Chambly Canal National Historic Site

It costs more to eradicate invasive species than to prevent them.

Parks Canada is using eDNA as an early prevention tool against invasive species. Their findings will support the creation of a rapid response plan in cases where the fish is detected in new waters.

-

A promising new tool

eDNA is one tool Parks Canada is using to help monitor and restore healthy ecosystems. It shows promise as an innovative, less invasive, and efficient tool to complement traditional monitoring. Parks Canada and partners will continue to explore this and other new and emerging conservation tools.

.jpg)

.jpg)

- Date modified :

.jpg)

.jpg)