Auyuittuq National Park management plan 2010

Auyuittuq National Park

- Auyuittuq National Park Management Plan 2010 (PDF, 3.14 MB)

- ᐊᐅᔪᐃᑦᑐᖅ ᒥᕐᖑᐃᓯᕐᕕᒃ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ ᐊᐅᓚᑎᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐸᕐᓇᐅᑎᑦ (PDF, 3.58 MB)

Table of contents

- Foreword

- Recommendations

- Acknowledgements

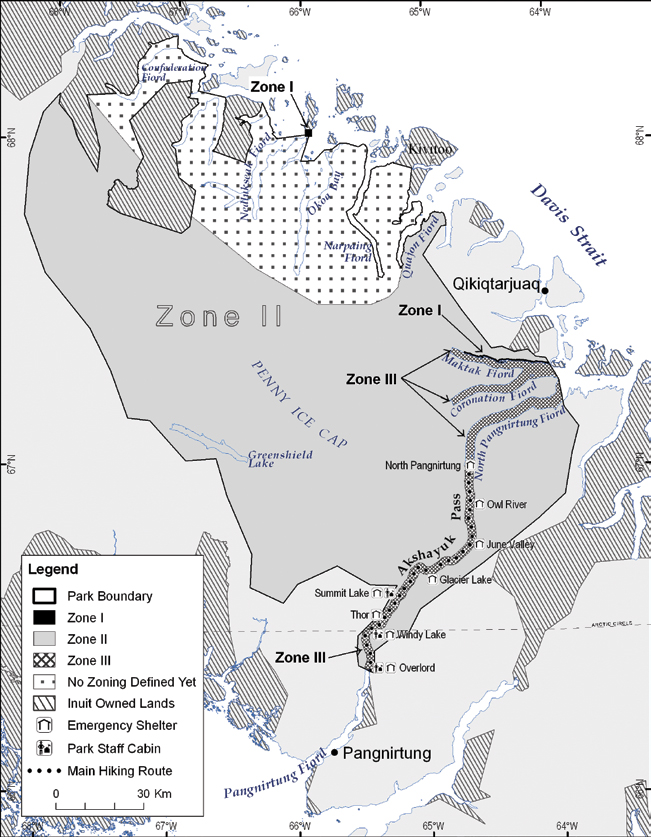

- In memory

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Importance of Auyuittuq National Park

- 3.0 Planning Context / Current Situation

- 4.0 Vision Statement

- 5.0 Key Strategies

- 6.0 Area Management Approach

- 7.0 Partnering and Public Engagement

- 8.0 Zoning

- 9.0 Wilderness Area Declaration

- 10.0 Administration and Operations

- 11.0 Monitoring

- 12.0 Summary of Strategic Environmental Assessment

- References

- Glossary

Figures

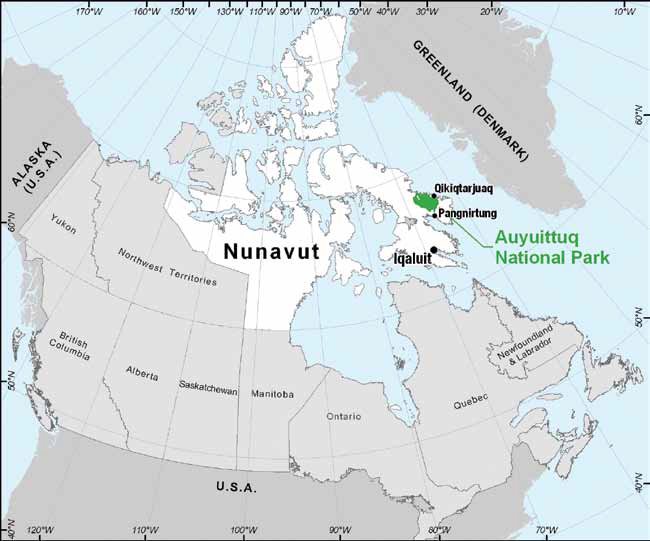

- Figure 1: Location of Auyuittuq National Park in Canada

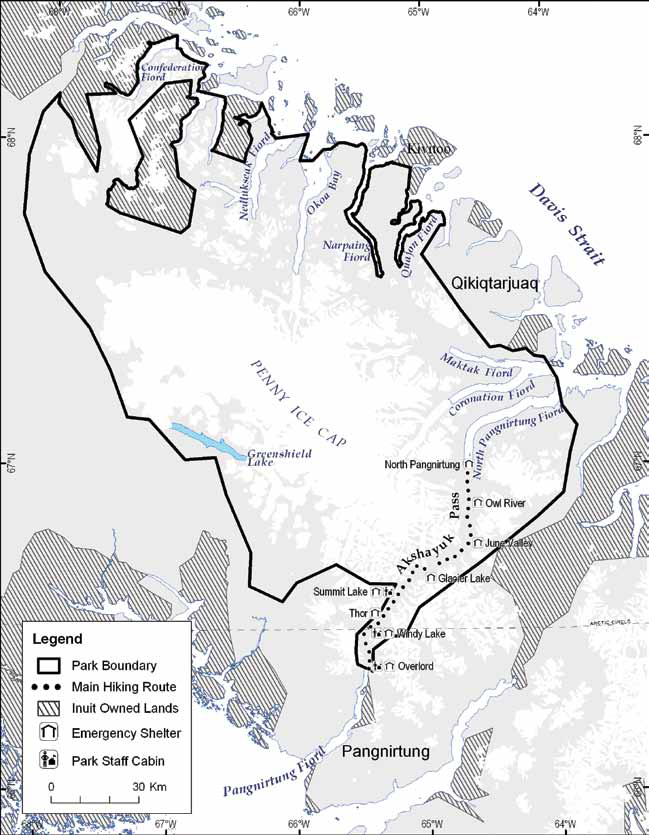

- Figure 2: Auyuittuq National Park of Canada

- Figure 3: Role of the Joint Park Management Committee

- Figure 4: Guiding Principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

- Figure 5: Ecosystem Indicators of Auyuittuq National Park

- Figure 6: Examples of Archaeological Features in Auyuittuq National Park

- Figure 7: Cruise ship Tourism in Nunavut and Auyuittuq National Park

- Figure 8: Polar Bear Safety

- Figure 9: Auyuittuq National Park Zoning

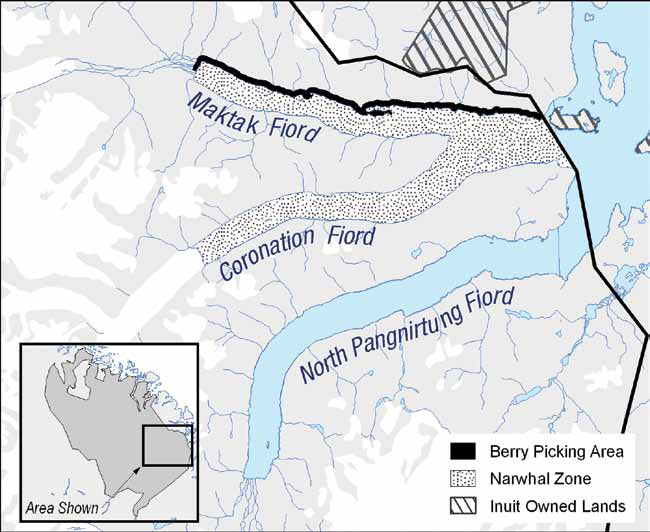

- Figure 10: Areas of Special Importance to Inuit

© Her Majesty the Queen in the Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2010.

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français.

ᐅᓇ ᐊᒥᓱᓕᐅᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᓪᓗᓂ ᓴᖅᑭᖅᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᒻᒥᔪᖅᑕᐅᖅ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑑᖓᓪᓗᓂ.

National Library of Canada cataloguing in publication data:

- Parks Canada.

- Auyuittuq National Park of Canada management plan.

- Auyuittuq National Park of Canada management plan [electronic resource]. Type of computer file: Electronic monograph in PDF format.

Issued also in French under the title:

Parc national du Canada Auyuittuq, plan directeur

Issued also in Inuktitut under the title:

Aujuittuq mirngguisirvik kanatami, aulattinirmut parnautit / ᐊᐅᔪᐃᑦᑐᖅ ᒥᕐᖑᐃᓯᕐᕕᒃ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ ᐊᐅᓚᑎᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᐸᕐᓇᐅᑎᑦ

- Paper: ISBN 978-1-100-15838-9 Cat. no.: R61-40/2010E

- PDF: ISBN 978-1-100-15839-6 Cat. no.: R61-40/2010E-PDF

- Auyuittuq National Park (Nunavut)--Management.

- National parks and reserves--Canada--Management.

- National parks and reserves--Nunavut--Management.

- Natural areas--Canada--Management.

- Natural areas--Nunavut--Management.I. Title.

Paper: FC4314 A88 P37 2010 333.78’30971952 C2010-980148-2

PDF: FC4314 A88 P37 2010 333.78’30971952 C2010-980149-0

Cover Photographs

top from left to right:

Hunting blind, Nedlukseak Fiord, Auyuittuq National Park © Natasha Lyons

Pauloosie Kooneeliusie, Tasialuit

Akshayuk Etooangat, Pangnirtung © Parks Canada

Anilnik Panilu

Management planning workshop at Maktak Fiord, Auyuittuq National Park © Parks Canada, Jane Chisholm

Large photograph: Auyuittuq National Park © Parks Canada

Akshayuk Etooangat, C.M., Elder from Pangnirtung, was known as a skilled traveller and hunter and for his knowledge of the land and the ocean. He travelled by dog team, including in the area that is now Auyuittuq National Park. He acted as a guide for doctors based in Pangnirtung for decades. Etuangat received the Order of Canada in 1995 and passed away in 1996. Akshayuk Pass, in the park, was named in his honour.

Anilnik Panilu, Elder from Kivitoo, was known as a skilled hunter and traveller and a provider for his community. He was very knowledgeable about wildlife and hunting. Panilu used to travel from Kivitoo to Pangnirtung to trade. He travelled this route by rowing a boat from Kivitoo to North Pangnirtung Fiord and then walking through the area that is now Auyuittuq National Park to reach Pangnirtung, and returning back to Kivitoo through the same route.

Pauloosie Kooneeliusie was from Qikiqtarjuaq. He travelled extensively in and around Auyuittuq National Park and was an experienced hunter and provider for his family and the community. Pauloosie was a long time outfitter who led adventure trips north of Qikiqtarjuaq and North Pangnirtung, Maktak and Coronation fiords. He promoted cultural tourism using traditional Inuit methods of travel by dog teams. Pauloosie shared his knowledge during the establishment of the National Park.

Foreword

Canada’s national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas offer Canadians from coast-to-coast-to-coast unique opportunities to experience and understand our wonderful country. They are places of learning, recreation and inspiration where Canadians can connect with our past and appreciate the natural, cultural and social forces that shaped Canada.

From our smallest national park to our most visited national historic site to our largest national marine conservation area, each of these places offers Canadians and visitors several experiential opportunities to enjoy Canada’s historic and natural heritage. These places of beauty, wonder and learning are valued by Canadians - they are part of our past, our present and our future.

Our Government’s goal is to ensure that Canadians form a lasting connection to this heritage and that our protected places are enjoyed in ways that leave them unimpaired for present and future generations.

We see a future in which these special places will further Canadians’ appreciation, understanding and enjoyment of Canada, to the economic well-being of communities, and to the vitality of our society.

Our Government’s vision is to build a culture of heritage conservation in Canada by offering Canadians exceptional opportunities to experience our natural and cultural heritage.

These values form the foundation of the new management plan for Auyuittuq National Park of Canada. I offer my appreciation to the many thoughtful Canadians who helped to develop this plan, particularly to our dedicated team from Parks Canada, the Auyuittuq Park Planning Team, the Auyuittuq Joint Park Management Committee, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq, and other government departments, organizations and individuals. They have all demonstrated their good will, hard work, spirit of co-operation and extraordinary sense of stewardship.

In this same spirit of partnership and responsibility, I am pleased to approve the Auyuittuq National Park of Canada Management Plan.

Qikiqtani Inuit Association

Dear Minister,

Over the last few years, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) has been involved in the cooperative development of the second National Park management in Nunavut - the Auyuittuq National Park Management Plan.

In 1993, the Government of Canada and Inuit signed the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (NLCA) that enabled both parties to establish Quttinirpaaq National Park following the negotiation of an Inuit Impact and Benefits Agreement (IIBA). The signing of the umbrella IIBA for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks in August of 1999 has provided for a shared vision between Inuit and Parks Canada. This relationship has strengthened Inuit participation in the planning, management and operation of national parks in Nunavut.

The Joint Park Management Committee is the key cooperative management body that approves the final draft of the management plan and jointly recommends it to the Minister responsible for Parks Canada.

The Qikiqtani Inuit Association provided comments and advice on a range of park management issues detailed in the Auyuittuq Management Plan throughout the park management planning process.

QIA is commending the cooperative development of Auyuittuq's 15-year vision which recognizes the importance of Inuit culture and traditions in the protection and conservation of resources. We look forward to contributing towards the completion of the Sirmilik management plans in the future.

Nunavut Wildlife Management Board

July 13, 2010

Dear Minister Prentice:

The Nunavut Wildlife Management Board is pleased to provide you with its endorsement of the Auyuittug National Park Management Plan, upon completion of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (NLCA) decision-making process and your acceptance of the NWMB’s approval decision of the management plan as per S 5.2.34 (c) of the NLCA.

The cooperative and holistic approach employed by Inuit and Parks Canada in the management of the Park is fully reflected in the Management Plan. The Management Plan is committed to protecting and maintaining the ecological integrity of the Auyuittuq National Park through appropriate consideration of both Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and scientific knowledge.

Together, these complementary sources of knowledge will serve as powerful tools for the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board and other responsible agencies in understanding ecological patterns and processes in maintaining the Park's biodiversity. They will also assist in determining suitable responses to the challenges posed by ecological stressors in the Park, such as climate change and the impacts on wildlife and habitat by Park users and visitors.

The Nunavut Wildlife Management Board looks forward to working in cooperation with Parks Canada and the Joint Park Management Committee to ensure that our shared wildlife and habitat management goals and objectives are achieved in Auyuittuq National Park. It is through such a partnership approach that Inuit will confidently continue to be an integral part of Auyuittug’s unique, healthy and precious arctic ecosystems.

Recommendations

Auyuittuq National Park of Canada management Plan recommended for approval and original signed by

Alan Latourelle

Chief Executive Officer

Parks Canada

Nancy Anilniliak

Field Unit Superintendent, Nunavut

Parks Canada

Manasa Evic

Chair

Auyuittuq Joint Inuit/Government Park Planning and Management Committee

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this plan involved many people. The input of this diverse group of individuals has resulted in a plan that will guide the management of the park for many years. The following individuals have made special contributions to the plan and deserve mention:

Auyuittuq National Park of Canada Park Planning Team

Loseeosee Aipelee, Clyde River

Harry Alookie, Qikiqtarjuaq

Nancy Anilniliak, Parks Canada

David Argument, Parks Canada

Delia Berrouard, Parks Canada

Frances Gertsch, Planner, Parks Canada

Eric Joamie, Pangnirtung

Eliyah Kakudluk, Qikiqtarjuaq

Sila Kisa, Pangnirtung

Karen Lassen, Parks Canada

Jaypetee/Zebedee Qappik, Pangnirtung

Pete Smillie, Parks Canada

Auyuittuq Joint Inuit/Government Park Planning & Management Committee

Rosie M Aullaqiaq

Manasa Evic, Chair

Tommy Etuangat

Abraham Keenainak

Sila Kisa

Davidee Kooneeliusie

Solomonie Nookiguak

Hezekiah Oshutapik

Don Pickle

Jayco Qaqqasiq

T. Bert Rose

Sakiasie Sowdlooapik

Other Parks Canada Staff

Gary Adams

Nancy Anilniliak

Paul Ashley

Margaret Bertulli

Jane Chisholm

Lynn Cousins

Jane Devlin

Lyle Dick

Graham Dodds

Lori Dueck

Catherine Dumouchel

Marco Dussault

Kathryn Emmett

Billy Etooangat

Kristy Frampton

Heather Gosselin, Planner

Kathy Hanson

Paula Hughson

Tom Knight

Davidee Kooneliusie

Daniel Kulugutuk

Maryse Mahy, Planner

Gary Mouland

Rebecca Nookiguak

Margaret Nowdlak

Darlene Pearson

Soonya Quon

Vicki Sahanatien

Pauline Scott

Elizabeth Seale

Monika Templin

Suzanne Therrien-Richards

John Webster

Monty Yank

Inuktitut translations and interpretation during this planning process were completed by a number of individuals, including Harry Alookie, Connie Alivaktuk, Jose Arreak, Lavinia Curley, Julia Demcheson, Andrew Dialla, Emily Illnik, Innirvik, Leetia Janes, Jonah Kilabuk, Rebecca Mike. The primary French translators were France Pelletier and Jean-Paul Gagné. Qujannamik!

In memory

Eliyah Kakudkuk

Eliyah Kakudluk was a member of the Auyuittuq Park Planning Team in 2006 and 2007. He was a very knowledgeable Elder from Qikiqtarjuaq who was among the last Inuit from that community to travel through the park area by dog team. He shared his knowledge and insight on the park’s wildlife with the Park Planning Team. Eliyah passed away in 2007. His knowledge, wisdom and contribution will not be forgotten.

Jacopie Koksiak

Jacopie Koksiak was an Elder from Qikiqtarjuaq. He shared his knowledge of the park’s cultural resources and history, especially the sites on Maktak Fiord. He provided recommendations on ways to monitor cultural resource sites to protect them in the long term.

Thomasie Alikatuktuk

Thomasie Alikatuktuk was elected as the President of the Qikiqtani Inuit Association from 2002 to 2009. He left his position due to health reasons and passed away shortly after. Thomasie was born in 1953 just outside of Pangnirtung, in Tuapait camp in the Cumberland Sound area. He was involved in several organizations in the Qikiqtani region during his tenure as President. Thomasie was one of the original supporters in the establishment of Cumberland Sound Fisheries. Thomasie was also well known for his art work. He was respected for his leadership of the Qikiqtani Inuit Association. His legacy will be remembered by Nunavummiut.

Other Elders have an important role in the history of the park and its adjacent communities, including the late Adamee Nookiguak who had a camp at North Pangnirtung Fiord and the late Angmarlik who had camps at Mikkattalik, as well as the late Akshayuk Etooangat, Anilnik Panilu and Pauloosie Kooneeliusie.

Executive Summary

Auyuittuq National Park of Canada is located on Baffin Island’s Cumberland Peninsula, almost entirely within the Arctic Circle in Canada’s eastern arctic. At 19,089 km2, it is among the largest national parks in Canada. Auyuittuq National Park is located next to the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in Nunavut.

The park is cooperatively managed by Inuit and Parks Canada in accordance with the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement and the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement of Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks.

Two key strategies will guide the work for the foreseeable future in the management of the Park. Working with local Inuit communities is central to both strategies. Each key strategy will build on existing relationships in ways that enable the Agency to better carry out its mandate and enable communities to meet their aspirations.

Key strategy 1:

Engaging communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in connecting visitors to the land, marine ecosystems and Inuit culture

This strategy focuses on working with the adjacent communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq to enhance visitor experiences in Auyuittuq National Park and diversify opportunities for visitor experience. Initiatives will respond to emerging regional tourism trends and community aspirations.

Research has shown that visitors who travel to the park are interested in discovering a remote, challenging and majestic area. They also hope to interact with local communities and learn about Inuit culture. As well, emerging and new tourism audiences have been identified, including the cruise ship industry and business travellers who extend their stay in Nunavut by a few days to visit other attractions in the territory.

The visitor experience begins in the adjacent communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq, where visitors receive their park orientation and provide benefits to the communities. Additional opportunities for visitor experience provide benefits to the adjacent communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq, increase the connection of visitors to Inuit culture and history, and offer opportunities to enjoy the park’s glaciated landscape and fiords.

This strategy takes a win/win approach, working with the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq to enhance opportunities for visitor experience and in doing so assisting the communities to benefit from tourism.

Key strategy 2:

Gathering and sharing knowledge to build connection to place

This strategy focuses on developing a common understanding of Auyuittuq National Park’s ecosystems and cultural resources with Inuit. This common understanding relies on Inuit knowledge and science and builds a trusting relationship between Inuit and Parks Canada. Knowledge of the park will be shared with youth, visitors and all those involved in park management and operations. It will serve to strengthen the connection of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq and other Canadians to Inuit culture and history and to the park’s glaciated landscape and fiords. This knowledge will also contribute to education products and management actions to preserve natural and cultural resources.

Up to now, educational messages relating to the park have predominately focussed on public safety. While these messages are still needed, the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq have expressed an interest in connecting youth to the Park, to Elders and Inuit culture, and they have stressed the need to use Inuktitut place names.

This strategy aims at fulfilling these needs by gathering knowledge and developing a common understanding of the park. It emphasizes the development of interpretive materials and messages about the park’s cultural resources, past and present Inuit uses of the area, and the park’s glacier, tundra, freshwater, and coastal/marine ecosystems.

Figure 1: Location of Auyuittuq National Park in Canada

Figure 2: Auyuittuq National Park of Canada

1.0 Introduction

Auyuittuq National Park of Canada is located on Baffin Island’s Cumberland Peninsula, almost entirely within the Arctic Circle in Canada’s eastern arctic. At 19,089 km2, it is among the largest national parks in Canada. The Park is located next to the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in Nunavut.

Auyuittuq National Park was first established in 1976, as a national park reserve and it became a national park in 2001. It is cooperatively managed by Inuit and Parks Canada in accordance with the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement of Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks and the Canada National Parks Act.

The park is composed of a terrestrial component centred on the Penny Ice Cap and the valleys and uplands surrounding it, and a marine component of deep and rugged fiords. The area has been used by ancient cultures as evidenced by the cultural resources that have been identified in certain parts of the park. The park is still used by Inuit today, for various cultural and harvesting activities.

Most visitors to the park come in the summer for hiking or climbing, and in the spring for skiing. Cruise ship visitation in Nunavut has increased over the past few years and is expected to continue to expand.

Management of the park has followed direction from the park’s Interim Management Guidelines of 1982, a draft management plan of 1994 and, more recently, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement and Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement of Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks.

1.1 Purpose of the Management Plan and Integration of the Agency’s Mandate

This management plan, when completed, will be the key accountability document for Auyuittuq National Park to the Canadian public. It provides the framework for how Parks Canada, Inuit, stakeholders and the general public will work together to manage the park for the long-term. In doing so, this plan contributes to achieving Parks Canada’s strategic outcome:

“Canadians have a strong sense of connection, through meaningful experiences, to their national parks, national historic sites and national marine conservation areas, and these protected places are enjoyed in ways that leave them unimpaired for present and future generations.”

The plan outlines how Parks Canada’s legislated mandate of protection, education and enjoyment of the national park will be met. It presents a vision and identifies key strategies, an area management approach and zoning plan that address the park’s visitor experience, public education and protection issues in an integrated, holistic manner. The key strategies and area management approach, in particular, help to ensure that actions for protection, visitor experience and public education are mutually supportive. They also assist in creating greater clarity for the public and staff on how the vision will be achieved, and they aim at making it easier to implement the management plan and to ensure that an integrated approach carries through into day-to-day operations and decisions.

1.2 Integration of the Agency’s Mandate in the Management of Auyuittuq National Park

This management plan focusses on two key strategies to implement Parks Canada’s integrated mandate:

- Engaging communities in connecting visitors to the land, marine ecosystems and Inuit culture.

- Gathering and sharing knowledge to build connection to place.

Using these strategies and an area management approach and zoning plan, this management plan aims at addressing in a holistic manner Parks Canada’s mandate in Auyuittuq National Park.

This plan also attempts to use guidance and principles from both Inuit knowledge and scientific information.

1.3 Cooperative Management

Inuit and Parks Canada manage Auyuittuq National Park cooperatively. The Joint Inuit/ Government Park Planning and Management Committee (Joint Park Management Committee)Footnote 1 is the cooperative management committee for the park. The role of the Committee is to advise Parks Canada, the Minister responsible for national parks, the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board and other agencies on all matters related to park managementFootnote 2.

The creation of the Joint Park Management Committee was provided for in the Nunavut Land Claims AgreementFootnote 3. The Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement created, and outlined the details of structure and responsibility, for the Committee. Each member of the Joint Park Management Committee has the responsibility to act impartially in the public interest and for the public goodFootnote 4.

The first members of the Joint Park Management Committee were appointed in fall of 2000 and held their first meeting in March 2001. The Committee meets at least twice each year and consists of six members, three appointed by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association and three appointed by the Government of Canada.

When possible, Parks Canada facilitates the participation of Joint Park Management Committee members and other members of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in field trips to the park to participate in cultural resource inventories, management planning meetings or other projects.

Figure 3: Role of the Joint Park Management Committee

The role of the Joint Park Management Committee includes, but is not limited to, involvement in the following mattersFootnote 5:

- outpost camps;

- carving stone;

- water licences;

- the protection and management of archaeological sites and sites of religious or cultural significance;

- park planning and management;

- research;

- park promotion and information;

- park displays, exhibits and facilities;

- visitor access to and use of the park;

- employment and training of Inuit employees;

- economic opportunities;

- participation in the joint review of the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement of Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks; and

- changes to the boundaries of the park.

1.4 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and Inuit Knowledge

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit refers to the knowledge and understanding of all things that affect the daily lives of Inuit and the application of that knowledge for the survival of a people and their culture. It is knowledge that has sustained the past and that is to be used today to ensure an enduring futureFootnote 6.

Many of the values and guiding principles of Parks CanadaFootnote 7 align with the principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit described in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Guiding Principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

The guiding principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit that are recognized by the Government of Nunavut are as follows:

- Inuuqatigiitsiarniq: respecting others, relationships and caring for people.

- Tunnganarniq: fostering good spirit by being open, welcoming and inclusive.

- Pijitsirniq: serving and providing for family and/or community.

- Aajiiqatigiinniq: decision making through discussion and consensus.

- Pilimmaksarniq/Pijariuqsarniq: development of skills through practice, effort and action.

- Piliriqatigiinniq/Ikajuqtigiinniq: working together for a common cause.

- Qanuqtuurniq: being innovative and resourceful.

- Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq: respect and care for the land, animals and the environment.Footnote 8

Inuit knowledge is a key aspect of the cooperative management of Auyuittuq National Park. The Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement requires that the park’s management planning program give equal consideration to scientific information and Inuit knowledge and the role of Inuit knowledge in research and public information programs is reviewed by the Joint Park Management Committee as part of its approval processFootnote 9.

The Nunavut Field Unit of Parks Canada has led an Inuit Knowledge Project (2005-2010) in three of the Nunavut national parks, including Auyuittuq National Park. The project aims to address the fact that Inuit understanding of national park ecosystems and surrounding areas has not received adequate attention. It strives to enhance our understanding of the parks, increase capacity of Parks Canada and communities to engage in collaborative research and management and gain a greater understanding of Inuit knowledge, skills, expertise and perspectives. The knowledge, experience and approaches developed in the project will be used by the staff of Nunavut national parks to im¬prove and strengthen Parks Canada’s ecological integrity research and management programs, to strengthen local Inuit involvement in park management and enhance visitor experience and public education programs.

1.5 Regional Context

Auyuittuq National Park is located on Baffin Island, immediately north of the Cumberland Peninsula along Davis Strait. The park’s nearest communities are Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq. Pangnirtung has a population of approximately 1,325Footnote 10 and is located 32 km south of the park along Pangnirtung Fiord. Pangnirtung is a major centre for Inuit art and has a strong wage economy with government and commercial fisheries providing the bulk of employment. Qikiqtarjuaq is located on Broughton Island, 82 km to the northeast of Auyuittuq National Park in Davis Strait. Qikiqtarjuaq now has a population of approximately 473Footnote 11. It is developing its commercial fishing industry, along with the communities of Grise Fiord, Resolute Bay and Arctic Bay. The landscape, wildlife, culture and art of both communities and their surroundings are very attractive to visitors. Traditional cultural and harvesting pursuits play an important role in both communities. Both communities have scheduled air service from Iqaluit, which is located approximately 300 km to the south of Pangnirtung and 400 km to the south of Qikiqtarjuaq.

1.6 Planning Process

The Canada National Parks Act requires that a management plan be developed and tabled in Parliament for each national park. A management plan must be developed with the involvement of the Canadian public and be formally reviewed every five years.

The Nunavut Land Claims AgreementFootnote 12 also requires the development of a park management plan for the national parks in Nunavut. The Nunavut Land Claims AgreementFootnote 13 requires that this management plan accord with the relevant terms and conditions of the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement.

This management plan for Auyuittuq National Park was prepared cooperatively with the Park Planning Team and the Joint Park Management Committee. The final draft was presented for review and approval by the Joint Park Management Committee and the Government of Canada. The planning process has been and will continue to be guided by the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement, the Canada National Parks Act, Parks Canada’s Guiding Principles and Operational Policies and the involvement of the Canadian public.

Parks Canada, the Park Planning Team and Joint Park Management Committee organized partner, stakeholder and public consultation events to bring together key individuals to set direction for the park’s management. A variety of consultation techniques were used to engage the public in the planning program and to seek input on a draft of this management plan, including newsletters, workshops in the park, workshops in Pangnirtung, Qikiqtarjuaq and Iqaluit, radio call in shows, letters and public meetings. The communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq (Hamlet Councils, Hunters and Trappers Organizations, Elders Committees, Youth Groups, Women’s Groups, teachers, the tourism industry, Search and Rescue groups, Community Lands and Resources Committees, and the general public), the tourism sector, scientists, the Qikiqtaaluk Wildlife Board, the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, Nunavut Tunnagvik Inc., the Inuit Heritage Trust, representatives of the Government of Nunavut, other federal departments, environmental organizations, park visitors and other interested members of the public were also consulted on this management plan. Public documents have been available in Inuktitut, English and French and public meetings were held in all three languages as well.

Management plans for national parks are now developed after a State of the Park Report is prepared in order to report on progress towards meeting objectives and to ensure that planned actions are effective in achieving desired results. The five-year review of this management plan will be based on a State of the Park Report.

2.0 Importance of Auyuittuq National Park

Auyuittuq National Park is part of a family of national parks that protect representative examples of Canada’s landscapes and natural elements. They are natural areas of Canadian significance which are managed by Canada and designated by Parliament. National parks are key symbols of the Canadian identity that are managed under the Canada National Parks Act for the benefit, education and enjoyment of all Canadians so as to leave them unimpaired for future generations.

The National Parks System Plan divides Canada into 39 distinct “National Park Natural Regions” based on landforms and vegetation. Auyuittuq National Park represents the Northern Davis Natural Region (Natural Region 26). This natural region is one of mountainous terrain, long fiords, ice caps, glaciers and marine fauna. The region includes the northern extremity of the Canadian Shield and shoreline along Davis Strait.

The park was established as a national park after two agreements were signed between Inuit of Nunavut and the Government of Canada: the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement and the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement of Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks. The latter agreement describes the purpose of Auyuittuq National Park of Canada as follows:

The purpose of the park is:

- to protect for all time a representative natural region of Canadian significance in the Northern Davis Natural Region;

- to respect the special relationship between Inuit and the area; and

- to encourage public understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of the park, including the special relationship of Inuit to this area so as to leave the park unimpaired for future generationsFootnote 14.

The park is important for its geophysical, biological characteristics and cultural resources, the stories it reveals about ancient and modern cultures, and the associated visitor experience and public education opportunities.

3.0 Planning Context / Current Situation

The establishment of Auyuittuq National Park was initiated more than 40 years ago and was completed following the signing of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement.

- 1960s: Interest in establishing this part of Baffin Island as a national park was first expressed in the Government of Canada’s “Three North of Sixty” initiative.

- 1972: Land was withdrawn for Baffin Island National Park on February 22.

- 1975: In February, a competition was held in the communities of Broughton Island (now Qikiqtarjuaq) and Pangnirtung to select a name for the future park. The name Auyuittuq — the Inuktitut word for “the land that never melts” — was chosen.

- 1976: Auyuittuq National Park ReserveFootnote 15a was established on April 9 and protected 22,600 km2 on eastern Baffin Island.

- 1993: The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was signed in Iqaluit, Northwest Territories (now Nunavut) on May 25. During the land selection process as part of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement negotiation, Inuit selected approximately 3,500 km2 of terrestrial and marine areas to become Inuit Owned Land, thereby reducing the size of the park to 19,089 km2.

- 1999: The Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks was signed on August 12, 1999.

- 2001: On February 19, the Canada National Parks Act came into force enacting Auyuittuq National Park of CanadaFootnote 15b.

3.1 Ecosystems and Ecological Integrity

Auyuittuq National Park is representative of the Northern Davis Natural Region, an area comprising the south and east coasts of Baffin Island and the east coasts of Devon and Ellesmere Island. The park straddles the Arctic Circle in an ecological transition between the High Arctic and Low Arctic vegetation zones.

The harsh physical environment of the park, dominated by rock and ice, limits both the diversity and distribution of wildlife and plants. Only 20% of the park is covered by vegetation, with most of it occurring in valley bottoms and on lower slopes less than 500 m above sea level. The park is part of the northeastern edge of the Canadian Shield, and mountain peaks within the park are among the highest on Baffin Island and the Canadian Shield. The park interior is dominated by the Penny Ice Cap, a vast 6000 km2 expanse of ice and snow. Melt-water from the ice cap and other glaciers supplies inputs into numerous streams, rivers and lakes. Summit Lake, as the name suggests, sits high along the Akshayuk pass and feeds the two major river systems in the park; the Weasel River which flows south from Summit Lake and the Owl River which flows north. Several other glacier fed streams and smaller lakes occur in the park. Greenshield Lake, the largest lake in the park is surrounded by vegetated tundra and provides habitat for many of the wildlife species found in the park.

Along the coast, glaciers have incised the valley floors below sea level, creating deep, narrow fiords with vertical walls up to 900 m in height. These coastal/marine areas, including the northern fiords of the park, are rich in wildlife. Six species of marine mammals (including the polar bear) have been recorded in the park and an additional seven species found in adjacent waters may use the park as well.

Eight species of terrestrial mammals are found in the park and 28 species of birds breed in the park (with another 11 species suspected to breed in the park)Footnote 16. Thirteen species of freshwater and marine fish have also been recorded in the park. Several other species of wildlife found in the greater park ecosystem on the Cumberland Peninsula, and in the waters of Cumberland Sound and Davis Strait adjacent to the park may sometimes occur within park boundaries.

The greater park ecosystem encompasses a large area of relatively pristine wilderness with a high level of ecological integrity. Today, Auyuittuq National Park is virtually indistinguishable from much of its surrounding greater park ecosystem. However, the park protects portions of the habitats required to sustain large animals that transcend boundaries, including caribou, polar bear, wolves and some marine mammals.

The Inuit communities of Qikiqtarjuaq and Pangnirtung (the second largest community on Baffin Island) are located to the east and south of the park, respectively. Community members engage in cultural and resource harvesting activities throughout the greater ecosystem, including the park.

Several species that occur in the park are being assessed through the Species at Risk Act process. The polar bear, the Eastern High Arctic / Baffin Bay population of beluga, and the narwhal have been identified by the Committee on the Status on Endangered Wildlife in Canada as species of special concern. The Government of Canada is currently considering whether these species should be listed under the Species at Risk Act.

The harsh climate and remote location have limited industrial activity in the region, but new technologies are opening the High Arctic to industrialization and global stressors of climate change and long range transportation of airborne pollutants are causing impacts across the north. As more of the Arctic opens to settlement and industrialization, Auyuittuq National Park will play an increasingly important role as an undisturbed ecosystem and benchmark from which to assess impacts of localized development.

A five-year Ecological Integrity monitoring strategy for Auyuittuq National Park was developed in 2008, and as part of Parks Canada’s Northern Bioregion Monitoring Program four ecosystem indicators (Figure 5) are monitored for Ecological Integrity: glaciers/permanent ice, tundra/barrens, coastal/marine and freshwater. The park’s ecological monitoring program is expected to continue to be enhanced during the life of this management plan.

Monitoring the vast ecosystems of Auyuittuq National Park presents very real logistical and financial challenges. To meet these challenges the Ecological Integrity monitoring program is built around three uniquely different means of monitoring that together will provide a credible, comprehensive, cost-effective and sustainable program given the logistical and financial challenges that all northern parks face. These methods are: monitoring on the ground by Parks Canada and its partners, remote sensing through Parks Canada’s ParkSpace program and through other agencies, and use of Inuit ecological knowledge.

The management planning and cooperative management processes for Auyuittuq National Park are also important means of addressing local Inuit perspectives. These processes are described in more detail earlier in this management planFootnote 17. Monitoring programs for the park are developed in this cooperative management context.

Figure 5: Ecosystem Indicators of Auyuittuq National Park

Glacier and Permanent Ice Ecosystems

Glaciers and permanent ice, cover approximately 8470 km2, or 40% of the landscape with the Penny Ice Cap covering about 28% and glacial cirques about 12%. This ecosystem plays a major role in the maintenance of the park’s systems through the influence on regional microclimate and water budgets for all the other systems of the park.

Coastal/Marine Ecosystems

Auyuittuq National Park has about 800 km of fiord coastline. The area is characterized by deep narrow fiords with vertical walls up to 900 m in height. It is here, and especially in the northeast corner of the park that wildlife is most abundant. The marine component, although small at about 7%, is especially diverse in wildlife. The important marine components are associated with the fiords of the northeast portion of the park.

Tundra/Barrens Ecosystems

One half of the park area (50%) is comprised of tundra/barrens ecosystems. Tundra vegetation accounts for about 20% of the park’s land area found predominantly through the Akshayuk Pass and Greenshield Lake Area, with approximately another 18% composed of bedrock. The other 12% is covered by non-continuous vegetation.

Freshwater Ecosystems

Freshwater is a comparatively small ecosystem in Auyuittuq National Park, comprising less than 3 % of the park’s surface, mostly in small lakes. They do, however, support landlocked populations of Arctic Char, an important species to the neighbouring Inuit communities. Also, precipitation and melt-water events occur across the entire landscape and the collection of water into rivers and streams provides a means to effectively monitor some aspects of overall park integrity. Seasonal and annual fluctuations in timing, flow and discharge from melting ice caps, glaciers and lakes impacts all the other systems in the park.

3.2 Cultural Heritage and Resources

Auyuittuq National Park and its surrounding region have a rich legacy of cultural resources that tell the story of human occupation of the area over the last few thousand years.

The earliest people on Baffin Island were of the Pre-Dorset and Dorset Culture. Pre-Dorset people entered the park area about 3500 years ago, developing into the Dorset Culture around 2800 years ago. The Dorset culture persisted until the thirteenth century A.D. The ancestors of these people probably originated in the Bering Strait region of Alaska before migrating across the Canadian Arctic.

A second wave of migration from Alaska in the thirteenth century AD resulted in the arrival of Thule people in the Eastern Arctic. Modern Inuit are descendents of the Thule people. The transition from Thule to Inuit culture occurred between A.D.1600 and 1850.

Within the park area, the earliest evidence of human occupation is that of the Dorset Culture and evidence of the Thule people is more frequent. The Thule way of life was highly adapted to a coastal marine and tundra environment. With dogs, sleds, umiat (large skin boats), and qajait (kayaks), the Thule people were highly mobile hunters of land and sea animals. Seasonal activities were dictated by the abundance and distribution of the hunted species.

The first direct contact between Europeans and Inuit as recorded in written accounts occurred in 1576 during the first of three voyages by the English mariner Martin Frobisher. However, there is considerable archaeological and other evidence of earlier contact between Dorset people and Norse in the area of Baffin Island. More extensive contact with Inuit occurred through interactions with whalers around 1820 and especially following the whaler William Penny’s establishment of a mission at Cumberland Sound in 1857.

With the advent of commercial whaling in the area, Inuit culture began to change. Seasonal hunting continued, but patterns changed to accommodate the whaling season as many Inuit were employed by the whalers. Settlement patterns also changed as the whaling stations became a focal point for the availability and distribution of European goods.

By the early 1900s, commercial whaling was no longer profitable, and most of the whaling stations closed. Inuit who had settled near the stations now had to move onto the land in search of food and furs for trade. They lived in small, semi-permanent camps, many of which were located in the same areas as the old Thule sites. A trading post was established in Pangnirtung by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1921. This was followed by an RCMP detachment in 1923, and an Anglican church in 1925. A hospital was opened in 1930.

East of the park, the permanent settlement of Qikiqtarjuaq was established in the early 1960s. Before this, Inuit of the Broughton Island region lived in semi-permanent camps on the land. The establishment of Qikiqtarjuaq was tied in with the construction of a DEW Line site in 1955.

Protection and education programs related to the park’s cultural resources are guided by Parks Canada’s Cultural Resource Management Policy and the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks. The Cultural Resource Management Policy directs Parks Canada to conduct inventories of cultural resources, evaluate their historical significance, consider their historic values in actions affecting their conservation and presentation, and monitor them to ensure that conservation and presentation objectives are met. The Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement of Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks directs Parks Canada to manage archaeological sites and sites of religious or cultural significance in a manner that:

- Protects and promotes the cultural, historical and ethnographic heritage of Inuit society, which includes Inuit traditional knowledge and oral history related to these sites; and

- Respects and is compatible with the role and significance of these sites in Inuit cultureFootnote 18.

To date, the inventory of Auyuittuq National Park’s cultural resources has recorded 134 archaeological sites. These sites were identified through field research with teams of archaeologists, park staff and Elders.

Archaeological assessments were conducted in the park area in 1969, 1972, 1973, 1980, 1984, 1998, 2002, 2003, 2007 and 2008. The archaeological/ historical sites documented within the park have been classified by cultural affiliation: 28% of the sites are Inuit sites, 4% belong to the Thule culture, 3% are European or whaling sites and 1% of the sites are from the Palaeo-Eskimo culture. For many sites (64%), the cultural affiliation is unknown or unconfirmed. The conditions of the cultural resources has been determined to be as follows: highly threatened (1 site), threatened (11 sites), possibly threatened (23 sites), stable or highly stable (11 sites) and condition unknown (88 sites).

Other information on the park’s cultural heritage has been collected. The Nunavut Field Unit of Parks Canada maintains a searchable database of oral histories that have been gathered from Elders and the Field Unit has contributed to collecting Inuktitut place names in and near the park.

The park’s programs on cultural resources are currently limited and it is expected that they will be developed or enhanced during the life of this management plan. The inventory of the park’s cultural resources is ongoing, cultural affiliation for the majority of known sites is unknown or undetermined at present, and additional work is needed to evaluate the historical significance of the park’s known cultural resources. The park’s monitoring program for cultural resources is in its inception and is expected to focus on key cultural resource sites, while educational products and programs on cultural resources are currently limited. Efforts to better connect visitors and local residents to the park’s cultural resources are needed.

Figure 6: Examples of Archaeological Features in Auyuittuq National Park

- Recent tent rings

- Sealskin tent rings

- Semi-subterranean houses

- Qammaiit

- Caches

- Puppy pens

- Recent hunting blinds

- Temporary shelters

- Possible Thule tent rings

- Exterior hearths

- Storage areas

- Qajaq stands

3.3 Importance of the park to Inuit

The park and its surroundings are important to the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq. InuitFootnote 19 from these two communities engage in various cultural and harvesting activities in and around the park. Cultural resources and Inuktitut place names in the park play an important role in maintaining the strong connection that Inuit have to the area. The cooperative management process mandated by the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement also contributes to maintaining local Inuit connection to the park, in particular through efforts to use both Inuit knowledge and science, and through the management planning process.

3.4 Visitor Experience and Tourism

Park visitorsFootnote 20 are drawn to Auyuittuq National Park by its impressive sheer-cliffed mountains, numerous glaciers, long fiords, mountain passes, Inuit culture and relative accessibility. They include non-beneficiaries from the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq as well as visitors from other regions of Canada or other countries. Visitors experience the park by day hiking, backcountry hiking, mountaineering, technical climbing, backcountry ski touring, glacier travel, guided snowmobile visits, occasional dog team trips, boating and, more recently, through cruise ship expeditions.

The park receives on average 500 visitors each yearFootnote 21, the majority of whom hike all or part of Akshayuk Pass. In 2009, there were approximately 380 visitors to the park.

Visitors are immersed in a dynamic landscape that offers opportunities to experience risk and to challenge themselves. The park demands visitors be experienced and prepared to meet the challenges associated with travelling in the Arctic. The many varied dimensions of a trip to Auyuittuq National Park help those who experience this place develop a better appreciation and understanding of the natural and cultural heritage of Canada’s Eastern Arctic and of the circumpolar world.

The characteristics, experience and expectations of visitors to Nunavut and Auyuittuq National Park were recently studied by the Government of NunavutFootnote 22 and by Parks Canada and partnersFootnote 23. In addition, information on visitor demographics, expectations and experience is collected by the park when visitors register and de-register.

The visitor exit survey conducted by the Government of Nunavut in 2006 identified factors that shape tourism in Nunavut, including the following:

- Most surveyed visitors come to Nunavut in the summerFootnote 24.

- The main activities in which they engage are shopping for art, visiting museums and cultural centres, hiking and wildlife viewing.

- Half of the visitors were on business and often stayed for an additional 5 days in the territory for holidays.

- Cruise ship passengers spent more money in Nunavut than other visitors, whose spending focussed on accommodation and food.

- Most visitors to Pangnirtung go to that community for leisure, while half of Qikiqtarjuaq’s visitors are there for business and the other half for leisure.

Based on this survey, Nunavut TourismFootnote 25 has concluded that there was an opportunity to develop the tourism industry and satisfy the needs of visitors by creating more products and services for visitorsFootnote 26.

The study conducted on Auyuittuq National Park by Parks Canada, the University of Montana and the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute has shown that visitors to the park have a diverse set of expectations for their experience:

- Their reasons for coming to the park include backpacking, wildflower viewing, glacier travel and rock climbing.

- They are attracted to the park by its remoteness and come to experience the adventure and freedom of travelling in arctic and mountain wilderness.

- Some visitors are very experienced climbers while others have never backpacked.

- Cultural issues and interacting with Inuit are a major part of the experience for some visitorsFootnote 27.

That study also identified 6 key “dimensions” that visitors are seeking to experience in the park: Serenity/Freedom, Challenge/Adventure, Naturalness, an Arctic Experience, Learning/ Appreciation, and Spirituality. These dimensions of the visitor experience in Auyuittuq National Park were confirmed in surveys of visitors to the park that were conducted between 2005 and 2008Footnote 28. Recent surveys of visitors have also provided information that is helpful in planning marketing of the park.

Visitation to Auyuittuq National Park is influenced by its proximity to the capital city of Iqaluit. The establishment of the Territory of Nunavut in 1999 has raised awareness of the park and its adjacent communities (Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq) and the flight from Iqaluit to these communities is relatively inexpensive. The ease of access brings visitors of a variety of skill levels, although the park’s remoteness and landscape demand experienced and independent wilderness travellers. There are some guided groups in the park, but most visitors hike, ski or climb as independent groups. The park’s spring ski season is April and May; the summer hiking and climbing season is late June, July and August.

Tourism to the park has important potential in the context of Canada’s Eastern Arctic. Realistically, the costs and small market associated with the park will keep the numbers of visitors low in comparison to other parks in Canada. However, in the context of local tourism benefits, the current and future numbers of visitors to the park are significant. The majority of the visitors to the park travel through Pangnirtung when they enter or exit the park. In the past two years, however, the number of visitors starting their trip in the park from Qikiqtarjuaq and traveling through all of Akshayuk Pass to Pangnirtung appears to have increased. The economic impact of the park’s backpackers, skiers, climbers and cruise ship visitors can be significant to both Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

Much work remains to be done to reach key audiences, build awareness of the park and connection to place, in particular in relation to the park’s ecosystems, cultural resources and Inuit culture. Community visits can enrich the experience both in advance and after park visits. There are opportunities to build the in-town service offer through additional services and products such as local tours, arts and crafts and cultural experiences. As well, the park may see a rise in visitors as cruise ship visitation increases and as more people learn about how easily the park can be reached. This will continue to bring new kinds of visitors to the park, including visitors who are seeking new ways of experiencing the park and visitors who may be without significant experience travelling in remote Arctic environments.

3.5 Public Outreach Education

Parks Canada has recently gone through a realignment to increase its capacity to deliver outreach and educations programs, including in the Nunavut Field Unit. Outreach and education programs for Auyuittuq National Park are starting to be developed in a more proactive manner.

Programs delivered by the Nunavut Field Unit include an Environmental Stewardship Program focussing on Parks Canada messages that are relevant to Nunavut and the Nunavut school curriculum. The park has also been delivering other school programs, it has been hosting film evenings at the Visitor Centre in Pangnirtung every week in the winter since 2008; the films that are shown are historic films of the region, films that relate to Inuit culture, and films relating to the natural and cultural importance of the park area. Other programs delivered to date have mostly been opportunistic presentations in schools and at educators’ or other conferences.

Messages to Nunavut audiences have, to date, focussed on raising awareness of Parks Canada and national parks in Nunavut, career opportunities within Parks Canada and the importance for youth to stay in school, and avalanche awareness. New programs will allow the park to expand on these messages.

To date, monitoring of these programs has been limited to tracking the number of participants and to engaging in informal discussions with individuals who have participated in these programs. Comments have been used to improve these programs.

Presently, the general awareness of the park in Pangnirtung, Qikiqtarjuaq and Iqaluit is probably high. At a national level, however, this awareness is probably quite low.

Auyuittuq National Park has the potential to play an important role in outreach and education in the adjacent communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq, the region, and Canada-wide. The park can be positioned in school curricula and in outreach programs aimed at broad audiences as a prominent feature of Canada’s north. New heritage presentation programs can also be developed for people who cannot access the park in person.

3.6 Public Safety in Auyuittuq National Park

Auyuittuq National Park is a remote park with a harsh Arctic climate and a mountainous and actively eroding landscape. The risks to public safety associated with the park have been analyzed in the park’s public safety risk assessment and they are regularly reiterated as key management issues by Inuit Elders and other members of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq. Public safety in Auyuittuq National Park is managed in accordance with the Nunavut Field Unit Public Safety Plan.

The most recent public safety risk assessment for the park has identified river crossings, polar bear encounters, snowmobile and boat incidents, weather, sea ice conditions, avalanches, crevasses and the potential for serious climbing incidents as the key public safety issues in the park. Somehave mostly affected community residents or researchers. As well, the park has an extremely dynamic landscape that results from the interaction between water, ice, permafrost and rocks.

Information provided to prospective visitors to the park includes details on public safety hazards that are associated with travel in this northern wilderness. The remoteness of this area and limited rescue capabilities increase the risk of hazards from this challenging natural environment and make the prevention of incidents critical to of these issues apply to visitors, while others the safety of park users. All park users need to be prepared to deal with extreme and rapidly changing weather, unpredictable river crossings, a dynamic landscape, high winds and travel in polar bear country. Park users also need to be self-reliant and responsible for their own safety.

Public safety remains a concern that needs to be addressed as part of cooperative management, external relations, visitor experience, protection and public education programs to ensure the safety of Inuit, local residents, visitors, users and staff alike.

4.0 Vision Statement

Auyuittuq National Park is a place of towering, dark cliff faces brushed with gleaming ice and snow. Carved among the cliffs are deep, incised fiords rich with whales, seals and fish. Polar bears, the iconic Arctic mammal, hunt and den along the coast. Visitors quickly become aware of the dynamic nature of this area, where the land continues to be sculpted by ice, rock, wind and water. Archaeological sites reveal past stories of the people who used the park’s fiords and valleys through time, and this land still remains a special place for Inuit today. Inuit continue to carry out cultural and harvesting activities with their community and family and share stories, cultures and traditions with visitors.

Working together, Inuit and Parks Canada foster respect for and understanding of Auyuittuq National Park and the unique stories it holds. Inuit are deeply involved in all aspects of park management and operations, and participate on cooperative advisory committees enriching discussions and decisionmaking through their knowledge and culture.

Visitors from all over the world are drawn to Auyuittuq National Park inspired by the exotic nature of the landscape and Inuit culture. The Nunavut communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq provide an array of services to help the visitor truly experience and appreciate this special place.

5.0 Key Strategies

Key strategy 1:

Engaging communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in connecting visitors to the land, marine ecosystems and Inuit culture

Objective 1

To diversify and enhance visitor experience in Auyuittuq National Park and the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Implement the Explorer Quotient tool for the park, a survey accessible on the internet that can help match visitors’ needs, interests, expectations and desires with opportunities for experiences tailored to what they are seekingFootnote 29.

- Develop interpretive and educational products and programs on the park, on its ecosystems and on Inuit culture in cooperation with tourism stakeholders and knowledge holders of the communities of Pangnirtung and QikiqtarjuaqFootnote 30. Use Inuktitut place names in these products and programs.

- Develop interpretive products and programs for cruise ship visitors in cooperation with tourism stakeholders and knowledge holders of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Build on the cooperative relationship with the Association des francophones du Nunavut to enhance services to francophone visitors and tourism capacity in Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Encourage outfitters and other members of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq to develop programs, services or products for visitors.

- Develop displays and exhibits on the park in Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Identify additional opportunities for visitor experience in the park, including additional travel routes and day use opportunities.

- Conduct assessments of priority recreational activities guided by the Recreational Activity and Special Event Assessment Management Bulletin.

- Determine and report on whether changes are needed to infrastructure in the Park based on the park’s most recent risk assessment and the Nunavut Field Unit Safety Plan.

Objective 2

To enhance community relations.

- Improve Parks Canada’s facilities in Qikiqtarjuaq and work towards having a Parks Canada employee in the community year-round.

- Participate with the communities of Pangnirtung and in Qikiqtarjuaq in initiatives relating to sustainable tourism development. Use the Community Tourism Strategies developed in 2002 under the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks for guidance where appropriate.

- Deliver visitor service and interpretation training for members of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

Objective 3

To improve marketing of the park and promote the adjacent communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq by partnering with tourism organizations.

- Make every effort to advertize the park regularly in tourism publications, including international publications.

- Provide promotional materials or participate in tourism trade shows every year, including at international events.

- Develop a cooperative relationship with the cruise ship industry.

Key strategy 2:

Gathering and sharing knowledge to build connection to place

Inuksuit were developed for a specific purpose. People need to be informed about that. Older generations should tell the younger generations. We can even see them when travelling on skidoos. Harvesting areas are marked by Inuksuit. We need to do a better job at letting the public know about that. Elders once had to rely on the Inuksuit navigation system.… It would be nice to show the traditional navigation places, even if it is just in writing for young people, something they could read and be proud of, they could be proud of their tradition and heritage.

Objective 1

To use Inuit knowledge and science in inventories, monitoring, education and visitor experience programs of the park.

- Implement lessons learned from the Inuit Knowledge Project in the park’s ecological integrity monitoring program.

- Conduct cultural resource inventories in cooperation with the Inuit Elders and Youth of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in areas of the park that are not well known, with a focus on the northern parts of the park.

- Determine the historic value and identify the cultural affiliation of all known cultural resources in the park and produce a Cultural Resource Value Statement for the park.

- In collaboration with the Inuit Heritage Trust, collect Inuktitut place names in the park.

- Complete the development of monitoring programs for the park on visitor experience, public education, cultural resources and ecosystems and monitor the visitor experience, ecosystems and cultural resources in high use areas of the park.

- Develop a list of research priorities for the park that relates to park management objectives, including monitoring.

- Promote the practice for all researchers to share information on their research to the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq and other agencies.

- Promote the practice for all researchers to include funding in projects for community involvement and contribution, including input from key community groups or organizations.

- Encourage students from Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq to participate in Parks Canada-led inventory, research and monitoring programs.

- Promote the common understanding of the park’s natural and cultural resources in education and visitor experience programs and products.

Objective 2

To strengthen the connection of youth to Inuit culture and history and to the park’s glaciated landscape and fiords.

- Provide educational materials related to the park’s ecosystems, cultural resources and Inuit culture and history to educators in Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq and educational institutions in Nunavut.

- Develop a program to bring youth of the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq in the park with Elders, with a focus on sharing knowledge about park ecosystems, Inuit culture and land survival skills.

- Use Inuktitut place names in all interpretive products and programs for youth.

Objective 3

To strengthen the connection of other Canadians to Inuit culture and history and to the park’s glaciated landscape and fiords.

- Develop products and programs for public outreach education to other parts of Canada.

Objective 4

To cooperate with the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq to manage issues of common concern.

- Provide annual updates on park management to the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Implement lessons learned from the Inuit Knowledge Project on the process for applying Inuit knowledge in park management.

- Meet annually with the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq and community stakeholders to address issues of common interest, including in relation to public safety, cultural resources, ecological integrity, public outreach education and visitor experience.

- Use Inuktitut place names in all communications programs and products for the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Maintain regular contact with the communities of Qikiqtarjuaq and Pangnirtung and community stakeholders to ensure that park operations and programs are sensitive to the cultural and harvesting needs and aspirations of the communities of Qikiqtarjuaq and Pangnirtung.

- Report on the implementation of the Auyuittuq National Park components of the Nunavut Field Unit Environmental Management Action Plan with the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq.

- Maintain a working relationship with the Department of National Defence to manage access and use of the Park by the Department of National Defence, the Canadian Forces and the Canadian Rangers in order to achieve mutual objectives while respecting the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreementand the Canada National Parks Act.

Figure 7: Cruise ship Tourism in Nunavut and Auyuittuq National Park

The consumer demand for Arctic cruising is growing and cruise ship capacity for Arctic itineraries is also growing. In Nunavut, cruise ship tourism has been on the rise since 2004.

| Area Visited | Number of Cruise ship Visits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

| Nunavut | 6 | 9 | 20 | 20 | 26 | 49 |

| Pangnirtung | n/a | n/a | 6 | 7 | 10 | 3 |

| Qikiqtarjuaq | n/a | n/a | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Auyuittuq National Park | n/a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

Parks Canada is beginning to develop relationships with some of the cruise industry companies and to deliver Cruise Interpreter-Attendant training to communities adjacent to National Parks in Nunavut — including Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq. Parks Canada employees have also delivered presentations on some ships.

Cruise ships have the potential to provide benefits to local communities, who could sell art and crafts, provide passengers with cultural experiences and share Inuit knowledge with a large audience, provide visitors with interpretation services, or as step-on guides or local experts.

6.0 Area Management Approach

The following three geographic areas within the park (Figure 2) will receive particular management focus because of their current and emerging patterns of use by visitors and local communities:

- Akshayuk Pass: Akshayuk Pass is the main travel corridor in the park for visitors, Inuit, researchers and park staff, and it contains most of the park’s infrastructure.

- Coronation Fiord to the head of Narpaing Fiord: Coronation and Maktak Fiords and the land between these fiords and Narpaing and Quajon Fiords are key areas for Inuit of Qikiqtarjuaq to engage in cultural activities and exercise their harvesting rights as well as for current and potential new visitor experiences.

- Okoa Bay to Confederation Fiord: The Northern part of the park, especially in and around the fiords, is also a key area for Inuit of Qikiqtarjuaq to engage in cultural activities and exercise their harvesting rights. Visitors currently do not travel to this part of the park much, but the area could provide further visitor experience opportunities and additional benefits to the community of Qikiqtarjuaq.

Area 1:

Akshayuk Pass

Akshayuk Pass (the Pass) is a mountain pass bordered on its southern and northern extremities by fiords that lead to the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq. The fiord on the Pangnirtung end of the Pass is not within the Park boundary, but the fiord on the Qikiqtarjuaq end, North Pangnirtung Fiord, is located within the park. It is the part of the park that has received the most attention to date:

- The Pass and North Pangnirtung Fiord are the parts of the park that receive most hikers, skiers and climbers and where most of the park’s operational activities occur.

- It is a travel route for Inuit travelling between the two communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq, still in use today.

- The Pass is the part of the park that contains infrastructure to increase the safety and comfort of visitors: There are currently 8 emergency shelters and outhouses, 2 emergency caches, 3 staff cabins, and 4 radio repeaters in or near the Pass.

- The southern part of the Pass, between the Overlord and Windy Lake cabins, is used for day use, including hikes and snowmobile trips to the Arctic Circle marker.

- In winter and spring, Pangnirtung residents appreciate visiting southern part of the Pass by snowmobile. North Pangnirtung Fiord is important to the community of Qikiqtarjuaq for cultural and harvesting activities as well as for tourism. It provides opportunities for visitor day use, including guided boat and snowmobile tours.

- The Pass provides opportunities for extending the visitor season in winter and spring, especially through guided snowmobile and dog-sled tours.

Objective 1

To increase the availability of products and programs for visitors.

- Promote day use opportunities, including guided snowmobile visits.

- Assess the feasibility of identifying day hikes along Akshayuk Pass.

Objective 2

To maintain and restore ecological integrity, protect cultural resources and respect Inuit culture and harvesting.

- Identify and report on options to limit the impact of hiking on trail erosion.

- Include messages in visitor orientation and education programs and products about the park’s ecosystems, ecological integrity and the importance of cultural resources in Akshayuk Pass and North Pangnirtung Fiord.

- Provide information for airlines, and aircraft operators and owners about Auyuittuq National Park, including at the Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq airports.

Figure 8: Polar Bear Safety

Parks Canada provides information to visitors and prospective visitors to Auyuittuq National Park about risks of polar bear encounters and means of reducing risks of problem encounters. Parks Canada also encourages visitors to hire local outfitters to travel in certain parts of the park or at times of the year where there is a greater risk of encounters.

Realizing the need to offer opportunities for visitors to experience the park safely while assisting with tourism development in the park’s adjacent communities, Inuit and the Government of Canada agreed that “[w]hen an Inuk acts as a guide in accordance with the Park Business Licence or transports one or more sport hunters and their equipment through the Park to a destination outside the Park as set out in Article 8.1.17 of the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks, he or she may carry and discharge firearms for self-protection or the protection of his or her clients.” (Article 8.1.19 of the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks). Parks Canada is amending its regulations to address this commitment and thus expand opportunities for visitor experience.

Area 2:

Coronation Fiord to the Head of Narpaing Fiord

This part of the park is accessible from Qikiqtarjuaq, by boat in the summer and by snowmobile in winter and spring. It is a complex area that is used by visitors and the community of Qikiqtarjuaq:

- Maktak and Coronation fiords have been used by visitors and residents of Qikiqtarjuaq for recreational purposes (snowmobiling, dog sledding) and by Inuit for cultural activities and harvesting (including berry picking on the North shore of Maktak Fiord and narwhal harvesting in Maktak and Coronation Fiords in the fall).

- The north shore of Maktak Fiord contains a high concentration of archaeological sites and cultural resources.

- Qikiqtarjuaq sometimes organizes a teacher’s orientation on the North Shore of Maktak Fiord in the fall.

- There are few facilities in these fiords other than an emergency cabin and an outhouse at the end of North Pangnirtung Fiord and a radio repeater near Maktak/North Pangnirtung fiords (outside of the park boundary).

- There is an outpost camp on the north shore of Maktak Fiord.

- There is some interest in Qikiqtarjuaq in developing guided hiking/skiing opportunities between Narpaing and Maktak Fiords.

- Narpaing and Quajon Fiords are not within the Park boundaries, but they are access points to the park and they are important for cultural and harvesting activities of the community of Qikiqtarjuaq.

Objective 1

To increase the availability of products and programs for visitors.

- Promote day use opportunities in Maktak and Coronation Fiords, including guided snowmobile visits.

- Determine, in cooperation with the community of Qikiqtarjuaq and the tourism industry, whether an additional hiking/skiing route between Narpaing and Maktak Fiords could be marketed as a guided opportunity.

Objective 2

To maintain and restore ecological integrity, protect cultural resources and respect Inuit culture and harvesting.

- Include messages in visitor orientation and education programs and products about the park’s ecosystems, ecological integrity and the importance of cultural resources in Maktak and Coronation Fiords and in the area between these fiords and Narpaing and Quajon Fiords.

- Inform visitors, users and the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq of the zoning plan and the periods when Maktak and Coronation fiords are closed, as required by the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement for Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik National Parks, because of their importance to Inuit for berry picking and narwhal hunting.

Area 3:

Okoa Bay to Confederation Fiord

This part of the park is the northernmost area of the park, between Okoa Bay and Confederation Fiord, and including Nedlukseak Fiord. It is an important area for the community of Qikiqtarjuaq and it is an area that could provide further visitor experience opportunities and additional benefits to the community of Qikiqtarjuaq:

- Inuit of Qikiqtarjuaq are engaged in cultural and harvesting activities in all these fiords.

- A fishing derby sometimes takes place in a lake on the east side of Nedlukseak Fiord.

- Some members of the community of Qikiqtarjuaq have expressed an interest in commercial fishing in lakes within this area.

- A concern was raised in Qikiqtarjuaq that the Inuit Owned Land parcel to the southeast of Confederation Fiord may have been misplaced.

- There is an interest from the community of Qikiqtarjuaq to develop additional visitor experiences in this northern part of the park that could benefit the community.

- Members of the community of Qikiqtarjuaq have reported safety concerns associated with travelling by boat in this part of the park.

Objective 1

To increase the availability of products and programs for visitors.

- Determine, in cooperation with the community of Qikiqtarjuaq and the tourism industry, whether additional visitor experience opportunities could be developed in the northern part of the park and whether parts of the area should be identified as Zone III to facilitate motorized visitor experiences.

- Work with the community of Qikiqtarjuaq to facilitate participation (snowmobile access and issuance of fishing permit) by non-beneficiary residents of Qikiqtarjuaq to the fishing derby, a community event in which mostly Inuit participate.

Objective 2

To maintain and restore ecological integrity, protect cultural resources and respect Inuit culture and harvesting.

- Include messages in visitor orientation and education programs and products about the park’s ecosystems, ecological integrity and the importance of cultural resources in the northern parts of the park, especially near the mouth of Nedlukseak Fiord.

- Consider the maintenance of ecological integrity, the protection of cultural resources and Inuit needs and aspirations in the determination of the zoning that would be appropriate for this part of the park.

7.0 Partnering and Public Engagement